Intel's secret plan

This giant box contains a super-hush-hush project that promises to transform Intel's business. Can the company inside millions of PCs find a way to power billions of phones and other gadgets?

|

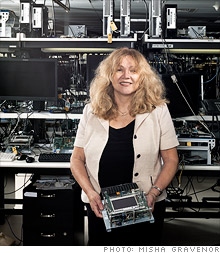

| An emulator tests a new processor that Intel hopes will find its way into mobile phones. |

|

| Elenora Yoeli, photographed in Austin, leads the team developing chips for consumer electronics and eventually smartphones. |

|

| Marketing head Maloney pushes executives to maintain margins even as Intel pursues high-volume businesses. |

(Fortune Magazine) -- At Intel's offices in Austin, visitors are welcomed by security, then pass through yet another gauntlet of guards and buffers as they make their way past a set of stout metal doors into the facility's fourth-floor labs.

Once inside, they find a chaotic tangle of circuit boards and wires and the animated chatter of engineers huddling around computers and workbenches. At one end of the room a mysterious-looking box about the size of a refrigerator conceals a project so top-secret that the engineers won't tell you its code name at first; later, one lets it slip: Medfield.

What the team in Austin - and their bosses at Intel's headquarters in Santa Clara, Calif. - will disclose is that the microprocessor they're testing inside that black box is the culmination of a decade-long effort to push the world's leading supplier of brawny, energy-hungry chips for enterprise computers and PCs into an important new market: portable devices.

The march started with the development of Centrino, a low-power Wi-Fi-enabled chip launched in 2003 that made laptops as functional as desktop computers. Last year Intel (INTC, Fortune 500) followed up with Atom, a super-low-power processor that is fueling the nascent market for so-called netbooks, those clutch-sized, bare-bones computers such as the HP Mini 1000 and Acer's Aspire One line.

For its next act, Intel is getting ready to launch an even lower-power "system on a chip" (silicon lingo for a single circuit that contains all the components of a computer), code-named "Moorestown," that marries the low-power Atom processor with graphics processors, a memory controller, and other circuitry - a potent combination of technologies that has the potential to propel Intel into businesses that have long eluded the chipmaker: consumer electronics and wireless gadgets.

Succeeding in this new market is critical for $38-billion-a-year Intel, which, like the rest of the industry, is seeing a slowdown in PC sales. Partly as a result of sluggish revenue in its main business, the company's stock has been hit badly (down 31% in the past 12 months, underperforming Nasdaq slightly), and in the fourth quarter Intel reported a 90% drop in profits year over year.

CEO Paul Otellini says he's confident that Intel can conquer consumer electronics, noting that such devices are increasingly becoming more like computers, something Intel knows intimately. "All consumer electronics - and I mean all - are aimed at bringing the Internet into devices," he says. Indeed, Otellini optimistically predicts that Moorestown will spawn a new category of handheld devices, much the way Atom seeded the netbook business.

Intel already pulls in $2 billion a year in revenue from "embedded" chips - processors installed in medical devices, cars, and other machines. Otellini believes the next generation of Intel chips, starting with Medfield, eventually will populate all electronics, from wireless phones to MP3 players to heart monitors and household appliances.

But the shift Otellini is gearing Intel to make is fraught with major challenges. The big dog in computers, Intel finds itself the underdog in consumer electronics and phones - a decade ago it tried to make a chip for small devices and failed miserably. And Intel's aggressive push into portable products threatens to upend its driven culture, which has focused on churning out high-performance chips, and its earnings statement. Instead of selling tens of millions of high-performance chips at, say, $100 a pop, Intel has to try to sell hundreds of millions of low-power products at $20 apiece.

"The soul of the company has to drift away from 'We build the biggest and the baddest' to 'We build the most,'" says Sean Maloney, head of sales and marketing at Intel. "And we have to do it in such a way that we don't move into these markets and tank our margins."

As we sit in a windowless conference room in Santa Clara, I ask him whether Intel absolutely has to crack into high-end cellphones and other "smart" consumer devices. Maloney, whom analysts believe is being groomed to take over after Otellini, draws in a breath, waits a beat, and then exhales. "Yeah, we do," he says softly. "Now we have to get there."

***

Intel has made company-changing bets before. Management seizes on a future trend, and the center of the company shifts. It happened in 1986, when then-CEO Andy Grove bet the future of Intel on the nascent PC and microprocessors. Several years later the company bet that speed would win the day, and in 1993 it unveiled another blockbuster, the Pentium chip, which helped desktop computers go mainstream.

Otellini is entrusting his company's current bet on small gadgets to a team led by Elenora Yoeli, a vice president in Intel's mobility group. Yoeli, who was part of the Israel-based team that delivered the Pentium4 processor in 2000, helped launch the Austin lab, and in 2004 received these marching orders: Build a chip compatible with Intel's existing architecture, and make it consume one-tenth the power of the latest Centrino chip.

She started with a $1 billion budget and a metaphorical blank sheet of paper. "We didn't spend time scaring ourselves - you don't do that at Intel," she says. The team built the chip by going through each feature and examining how much power it would consume. Features that delivered subpar performance or required too much power were ditched. The result: Atom, which met Yoeli's power and performance targets.

"The design went very well, and we have done something no one was really expecting us to do: take a small design and put it into one of the most advanced processors in the world," she says, allowing herself a small smile. Now she's doing it again with Moorestown.

Moorestown is actually two chips, each the size of the nail on your little finger, combined in a single module. One chip is the Atom processing core, which can handle graphics, video, and memory control. The second chip can enable a range of tasks, which might include digital imaging for a still or video camera, high-end audio, or some special security requirements. It is designed for flexibility, depending on the gadget the system is ultimately crammed into.

At the Austin lab Intel displays a handful of prototypes that suggest the kinds of devices that might eventually house the Moorestown platform: One looks like a long, narrow remote control with a smooth, flat face; another is slightly chunkier, with a five-inch screen dominating and no obvious buttons - clearly meant for watching video, or maybe gaming. A third device resembles an oversized iPhone.

All of them are smaller than a netbook but larger than a phone; executives admit they need to get Moorestown's power requirements down even more in order to reside in a smartphone. (That's where Medfield comes in: It will be one chip instead of a two-chip system. That will make it a more efficient power user, suitable for phones. Sources expect Medfield to appear in devices in 2011.)

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More