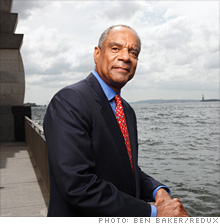

Crisis chief: AmEx's Chenault

The American Express CEO managed his company successfully through the financial meltdown. And while things are looking up, Kenneth Chenault's outlook isn't completely cheery.

|

| Kenneth Chenault, CEO of American Express |

(Fortune Magazine) -- American Express CEO Ken Chenault is one of the few Wall Street chiefs who have come through the financial meltdown and recession looking good.

American Express (AXP, Fortune 500) has remained profitable through it all, and this summer it completely repaid its TARP funds -- earning the U.S. Treasury a 26% annualized return on its brief investment. The company recently reinstated its contributions to employee 401(k) accounts and rescinded a pay freeze imposed last year.

Chenault, 58, built his crisis-management skills in his first year as CEO when he led the company through 9/11, which devastated the travel business, sapped consumer spending -- and killed 11 American Express employees (company headquarters is across the street from the World Trade Center site). He says the experience taught him lessons that he applied this time.

And while the acute phase of this crisis is long past, he still faces major challenges. American Express's biggest market, the U.S., will probably grow slowly, if at all, for many months to come, and Washington is writing new regulations that could significantly constrain the company and the whole financial services industry.

Chenault talked recently with Fortune's Geoff Colvin about finding opportunity in the new normal, why rich consumers stopped spending in this recession, managing through crisis when your largest shareholder is Warren Buffett, and much else. Edited excerpts:

Ben Bernanke said recently, "The recession is very likely over." Do you agree?

Aspects of the technical recession may be over, but I have to focus on the signs of a real turn. We look at spending, and over the past several months we've seen a moderation of the decline in card billings, but card billings are still negative. On the positive side, we've seen improvement in write-off rates on our credit card portfolio, though the absolute rates are still high by historical comparisons. So we're not yet seeing those drivers that we think will contribute to very strong revenue growth.

As recently as midsummer, you were looking well into 2010 before you expected a real turnaround. Is that still what you're thinking?

I'm hopeful that we'll start to see more pronounced improvements in several areas. One is increased technology spending. Another is more growth in T&E [travel and entertainment] spending, because corporations need to get out there and grow their business, and they need to travel and spend. I'm also hopeful that affluent customers who have the capacity will start to spend more.

We just did a survey of some of our card members, and only one out of four felt that the worst of the recession was over. That's just perception, but it's important. We then asked, "If you had a found $500, how would you spend it?" They said they'd pay off regular bills and pay down debt.

On the positive side, 60% said their spending will remain the same or will increase. Young professionals were the most optimistic and said, "We think we'll also start to spend more on discretionary items." So at least some attitudes are starting to change.

The conventional wisdom at the beginning of the recession was that affluent consumers -- American Express customers -- would always have money and would continue to spend. It turned out just the opposite -- high-end consumers cut back the most. How come?

This is one of the most surprising developments, because in the past two recessions you did not see this level of decline of highly affluent customers.

In our franchise, the highly affluent customer, spending drops were deeper than for the average customer. Some of the reason was the precipitous decline in housing prices, particularly in two states, California and Florida, where you have a high percentage of affluent people.

Plus, obviously, the impact of the stock market on their overall portfolios. These customers have capacity to spend, but they had to draw back.

So was it the reverse wealth effect -- they felt poorer and spent less because of that?

It was the wealth effect, and events happened that impacted the level of uncertainty that they had. For all of us, things were happening that we just couldn't imagine. I think that had a profound psychological effect.

You have as good a window onto consumer behavior as anybody because of the millions of card customers you have. Based on what you see from inside American Express, what's the current state of the U.S. consumer?

Spending is focused on nondiscretionary items -- people are buying things that they have to. On the balancing side for us, the number of transactions has remained relatively stable while billings have declined. So the average ticket has gone down, but people are still -- fortunately for us -- taking the card out of the wallet, which gives me confidence that we're still in their mind.

We certainly have seen an increase in the savings rate, and from a societal standpoint, that's good. But that affects people's spending capacity -- our borrowing fueled the growth.

You're describing what some people call the new normal -- the new economic world that we're heading into. What's the rest of the picture?

The economy is going to grow slower than it did before the downturn, even when we recover. That emphasizes the criticality for large companies to have a global presence. You can't have a dependence on a single market. We look at countries like China, Mexico, Brazil, Russia, India -- the reality is that those growth rates are still healthy.

And as I look at my business, the penetration of plastic against cash and checks is still low. Companies will need to pursue a more diversified business model, but I think those companies that have what I call a focused diversified business model will be more successful. So we see ourselves covering the spectrum of payments, and we're looking at a range of global opportunities.

You were in the middle of the financial meltdown a year ago. Lehman failed, AIG had to be rescued, and much worse disasters seemed possible. What were your worst fears at that time?

I had a number of fears. The reality is that we were on the verge of an absolute disaster and collapse. I remember vividly when the commercial paper markets froze up. That was an incredibly scary experience.

What was very important was to decide the key areas you needed to prioritize. So I went from being very focused on growth to issuing a mantra for the organization that we're going to stay liquid, stay profitable, and selectively invest in growth. And the "stay liquid" part was in question.

You say we were on the verge of collapse, but that's kind of abstract. What did it mean in practical terms?

For a number of major companies, if you can't access the commercial markets, you can't fund your business. That's a big problem. You can't pay your bills.

From experiences that we had after 9/11, we had made some major efforts to improve our balance sheet and put ourselves in a position where we did not have to go into the market right away.

Without naming names, there were some very large companies that had to go into the market on a regular basis. Most of them have survived, but it was a very scary period. Some companies had a great fear that if there was not some opening in the commercial markets and some support from the government, they would go under.

You once told me that reputations are won or lost in a crisis. You were talking about 9/11. Were the lessons of that experience useful to you in ways beyond what you've mentioned?

Yes. For me one of the lessons from 9/11 is that you have to give the organization context for how you're acting, and you've got to communicate constantly, in this case particularly with all the changes that were occurring in the financial marketplace and in the economy.

We had to make sure that people understood why the company was concerned, what the big issues were facing the company, and then the reasons to be hopeful that we could deal with those issues. And 9/11 was a time when we had to do that immediately. That was incredibly helpful this time.

The difference from a leadership standpoint between 9/11 and now is that the financial markets have not collapsed -- and that is a fundamental difference. People realized after two or three months that things were getting better.

This has been and will continue to be a critical endurance test of making sure that you're dealing with the base issues that you need to with your company while also positioning the company for moderate- to long-term growth, and anticipating what else can go wrong as well as the opportunities out there.

Were the fates of various companies in this crisis determined in large part by the way they were managed back before the bad stuff happened?

Yes -- things happened suddenly, but the problems were building over a period of time. What's critical is, What were you doing with your balance sheet? How did you think about leverage? What level of risk were you taking in good times? What changes did you make that may have been harsh, but you were willing to implement them in good times? And then, very important from a leadership standpoint, was the need to be focused and decisive back in the good times. The hardest time to bring about change is in the good times.

In May, President Obama signed the Credit Card Reform Act of 2009, which among other things will restrict your ability to change the interest rates you charge. I presume you don't like that. Did the credit card industry need reform?

Simple answer: absolutely yes. There needed to be reforms relative to transparency and disclosure. There were issues relative to back-end fees, methods that made it difficult for the consumer to understand what the proper behavior was, and some of the penalties were too severe. The objectives of reform are and should be transparency, disclosure, giving customers the ability to make informed choices.

But I think the legislation went too far in one specific area, and that's risk-based pricing [i.e., charging riskier customers higher interest rates]. I can hold myself out as somewhat of an objective party because only 20% of our revenues depend on spread revenues [the difference between interest income and the firm's cost of funds]. Our revenues are really dependent on our merchant discount fees and our card fees. But when the ability to do risk-based pricing is negatively impacted, my prediction is that the availability of credit for the subprime customer who needs credit the most will be substantially reduced.

A big package of more general financial services regulation is moving forward in Congress. It could include a major new agency -- a consumer protection agency for finance -- that would regulate your business. Is that a good idea?

I'm concerned about it. As we look at the problems of the financial meltdown, I'm very supportive of what President Obama is saying relative to transparency, choice, and the need to stabilize our financial system. There are clearly gaps from a regulation standpoint. But my great fear is unintended consequences.

In financial service regulation there's a safety and soundness objective, and there's a consumer-protection objective. Those two have to be integrated.

If you have a government agency with the responsibility to design and recommend products, and it's separate from the safety and soundness regulation, then certain product designs could be put in place that will not comply with the safety and soundness objectives.

Do you favor any federal regulation of executive pay, which is also being considered by Congress?

In our proxy we had "say on pay" [a non-binding shareholder vote on approval of executive compensation]. We got 73.55% in favor of management's compensation program, which puts us very much at the high end.

At the end of the day, what's the philosophy of compensation? Some of the appropriate concerns out there are that compensation programs are too short-term-oriented. I believe in multiyear programs and a range of criteria to measure performance. I think it's very difficult for the government to get involved in the design of compensation programs.

We're looking at a world in which your biggest market, the U.S., will be growing more slowly, and your business may be constrained by new regulation. Where is opportunity for American Express?

If we have a great deal of uncertainty and distrust in the world, then consumers and corporations want to trust companies and brands that they believe will deliver on their promises. So our focus on customer service is critical because if we can provide a higher level of certainty in a world that is uncertain, that gives us a competitive advantage.

In addition, the penetration levels of plastic against cash and checks are very low -- with consumers, small business, the middle market, large corporations, and internationally. Fifty percent of corporations still pay by cash and check. It's inefficient, and we believe we have products and services that will manage that.

We're doing a "back to the future" on the charge card. That's our pay-in-full product at the end of 30 days. Consumers want discipline, and if we can bring that discipline of paying in full at the end of the month along with the service levels that we provide, plus the rewards and other programs we have, we think that's a tremendous opportunity for us to grow.

We also believe there are substantial opportunities in partnering with banks to issue American Express-branded cards, and we've had very strong success doing it globally.

Another area that we feel strongly about is that we have information we can use in very effective ways for a range of partners.

So, for example, what might be surprising is that the Darden (DRI, Fortune 500) restaurant chain [Red Lobster, Olive Garden, LongHorn Steakhouse, and other brands] relies on us to help it with site selection for its restaurants. We believe that our information, which we use in our own business and marketing, can be used by retailers, restaurateurs, and other corporations to improve their business, and that's an increasing area of focus for us.

Your competitors say that with the increasing popularity of debit cards and prepaid cards, American Express is going to be marginalized. Why are they wrong?

I've been hearing this for years, but our average spend has continued to grow [over the long term]. So that would be a factual refutation of those statements.

But what's also important is to look at the functionality of the debit card. It's a pay-in-full product. The economics are such that a fair amount of money on debit is made from overdraft fees, which are coming under increasing scrutiny in Washington.

Think of the American Express charge card as a delayed debit card, except it's paid at the end of 30 days. It has rewards plus a range of services and some very attractive capabilities. And we've got more that we're coming out with. So we welcome the competition.

American Express became a commercial bank holding company last fall, like a number of other Wall Street firms. Does that mean you now want to start accepting deposits from consumers to maintain capital requirements?

We're a bank holding company, but I have zero interest in becoming a retail bank. I do believe there are targeted opportunities.

When the commercial markets froze last year, we were highly dependent on the wholesale funding market. What I think is a real testament to the trust that our brand has in an uncertain environment is that we launched a retail certificate-of-deposit product nine months ago, and through our deposit products in aggregate we have been able to raise over $20 billion, taking care of our funding needs.

What's important is that we also had those products delivered through third-party channels, other financial institutions that were selling our product vs. their own in-house product, and customers wanted ours. The maturities on these CDs are generally 24 months, so this is not hot money. People feel confident that with the backing of the brand, this is a product that they want to hold in their portfolio.

Just recently we launched a direct-deposit program for consumers. So we are selectively diversifying our funding sources, which is one of the important lessons from the crisis -- we needed to diversify our funding sources so that we were not overly dependent on the wholesale funding market.

I don't believe we have to go out and acquire a large retail bank with a branch system, because a lot of other assets come with that that I don't particularly want.

Your largest shareholder is Warren Buffett. How active was he in influencing the company during the financial crisis?

I enjoy talking to Warren because every time I talk with him I learn something. He is incredibly objective about the issues. It has been less about Warren giving specific advice than about him endorsing our course of action and giving us a perspective, particularly in some of the most dire times.

The other thing you see is a person who stays calm under pressure. In the darkest days I'd call him and say, "Warren, how you doing?" And he'd say, "Never been better." And very frankly, I'd say, "Give me a break. I certainly have been better." But that's the type of temperament he has. It's based on his analysis and his belief in the future.

It has been reliably reported that you were approached about leading some other financial firm during this crisis. What went through your mind as you thought about that?

I didn't really hesitate at all. First, I really do believe in the attributes of our brand and what American Express stands for. Second, I'm a very strong believer in the growth opportunities of the company and that we have a very exciting future. Third, I like the people.

My view was that size matters because you want to have enough size that you can make a difference. But what's more important is to be with an institution whose products, service, and people you can believe in fully. ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More