Time to drain Wall Street bonus pool?

Bonuses have soared at Goldman Sachs and other taxpayer-backed financial firms, but pay practices could clash with principles embraced by a revived Fed.

|

| Does Ben Bernanke hold the key on runaway pay? |

|

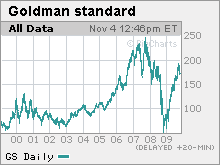

| Goldman shares have bounced as trading profits have soared. |

NEW YORK (Fortune) -- Is the Fed about to hit the brakes on the Wall Street gravy train?

A year after they survived the financial meltdown with considerable taxpayer help, Goldman Sachs (GS, Fortune 500) and Morgan Stanley (MS, Fortune 500) stand to spend $35 billion combined this year on employee compensation.

The average Goldman worker is on track to take down more than $600,000 in pay and perks -- in line with levels from 2007, before the economy cracked. Former Federal Reserve chief Paul Volcker said last month that Wall Street pay has gotten "grotesquely large."

But the bonus bubble could be peaking. After years of lassitude, the Federal Reserve is preparing to force big banks to abide by longstanding rules banning excessive or inappropriate banker pay.

What's more, regulators appear to be paying special attention to the risks posed by the lucrative trading that has sent profits at firms like Goldman and JPMorgan Chase soaring just months after last fall's brush with disaster.

Given the bruising the Fed has taken for its failure to act during the credit bubble, some commentators believe officials will flex their muscles.

"If they stand by the principles they laid out last month, we can expect them to give the big banks some pushback," said Eleanor Bloxham, who runs the Value Alliance/Corporate Governance Alliance advisory firm. "I think they're going to continue to push on all this to make sure we don't get another disaster like the one we just had."

The Fed said Oct. 22 that a review of bank pay practices will "focus on whether compensation arrangements provide employees incentives to take excessive risks that could threaten the safety and soundness of the banking organization."

Goldman and Morgan Stanley aren't big deposit takers or lenders. But they are subject to federal oversight of their pay practices, thanks to last year's decision to become Federal Reserve-regulated bank holding companies in the name of getting access to emergency funding.

A report last month from law firm Stroock & Stroock & Lavan notes that the Fed proposal "makes reference not only to employees commonly thought of as associated with banks, such as 'loan officers,' but also to 'traders.'"

Traders are a natural focus for compensation scrutiny, given the enormous upsurge in trading profits at taxpayer-backed banks such as Goldman, JPMorgan Chase (JPM, Fortune 500) and Citigroup (C, Fortune 500). Trading and principal investment revenue accounted for 81% of Goldman's total revenue in the third quarter, up from 45% a year ago.

The big banks have benefited from numerous forms of federal assistance beyond the Troubled Asset Relief Program loans that many have since paid back. They have also issued tens of billions of dollars of federally insured bonds and gained from the Fed's efforts to keep interest rates low.

"The problem is that there are a lot of subsidies with no strings attached, and now these guys are making huge sums of money," said Mark Sunshine, who runs a financial advisory firm that specializes in financial institutions. "Why should so many of the benefits flow to the traders?"

For now, they do because a dearth of competition and a rebound in financial markets has fed a profit surge at Goldman. Though it and Morgan Stanley are now Fed-regulated, they carry on the Wall Street tradition of paying out roughly half their revenue as employee compensation.

Both firms say their policies encourage pay for performance, balance short-term and long-term goals and discourage excessive risk-taking. Goldman says its compensation principles are in line with the guidance issued by the Financial Stability Board overseen by the Group of 20 rich nations.

But Bloxham said it's not clear that either firms has addressed the core of the Fed's proposal, which dictates that pay be based on so-called risk-adjusted returns.

Goldman says it manages prudently and conservatively. But the amount it stands to lose in a given trading day has risen since last fall.

Goldman has trumped that statistic by winning a huge proportion of its bets. The firm said this week its trading desk managed to make money on 64 of the 65 business days in the third quarter, including 36 $100 million-plus daily profits.

Todd Gershkowitz, a senior vice president at compensation consultant Farient Advisors, said those numbers show the runaway pay game hasn't changed on Wall Street.

"They're still accruing bonuses the same way they've done for 20 years, regardless of whether those revenues are high quality revenues," said Gershkowitz, speaking generally of big Wall Street firms. "The problem is that no one is pounding on the door saying cut this back."

Given that the sums set aside for bonuses come directly out of shareholders' pockets, Sunshine wonders why Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley haven't faced more questions about their pay levels.

"Will the trader making x millions of dollars really walk if you cut that back?" he asks. "I don't understand why the shareholders aren't going nuts." ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More