Search News

FORTUNE -- Athletes have trophies, gunslingers have notches, and David Boies has his wine cellars. The corridors en route are lined with framed headlines of his courtroom conquests. "The man who ate Microsoft!" proclaimed Vanity Fair; "Westy raised the white flag!" announced the New York Post, after Gen. William Westmoreland withdrew his libel suit against 60 Minutes. The climate-controlled cellars themselves, beneath his Georgian mansion in the northern suburbs of New York City, are stocked with 10,000 bottles of Bordeaux and California reds -- the evident spoils of success. But, as he tells you in a favorite tale, his beloved wine also becomes a reminder of what's made him the nonpareil lawyer of his time.

Back when the cellars were completed, he had his then-modest collection shipped from storage in a Manhattan warehouse. He went to find a '59 Margaux. "I knew exactly what I was looking for," Boies told me, "because it was a case I had earlier opened up and taken out six bottles and put in six different bottles of '66 Lafite Rothschild." It was his best case, and it wasn't there. Compulsive and methodical, he did an inventory and found nine other cases missing. The warehouse admitted it had shorted him, yet offered a paltry $150. The cases were worth $5,000, so he sued -- the only time he's been a plaintiff. He was then a partner at the venerable Cravath Swaine & Moore, which had platoons of associates who could have handled the matter. Boies insisted he'd do it himself.

The turning point in the case came when Boies spotted something another lawyer might have missed. At a deposition, the warehouse manager kept leafing through a folder. Boies asked, "Have you produced all those documents to us?" Boies was told yes, but he asked to see the documents just to be sure. What he found was an incriminating accounting of what had gone missing -- assembled by the warehouse long before Boies discovered his losses. Boies now raised the ante by charging fraud and demanding punitive damages. "It was great!" he recalls. "They calculated nobody would spend $25,000 of lawyer time on a claim for $5,000." They calculated wrong -- that Boies would not be Boies. The warehouse capitulated, and Boies got a settlement of $78,000 -- which he promptly spent on wine.

Through that trifling dispute -- long before he maneuvered a record $4 billion antitrust settlement for American Express (AXP, Fortune 500), vivisected Bill Gates in cross-examination, or argued Bush v. Gore for the loser -- you can learn a lot about David Boies, how he's so good and why he's still doing it. He has a formidable memory, he knows when to strike, and he thrives on litigation as sport. Sure, he likes the multimillion-dollar wine collection, but even more how he started it. "I love to litigate," he says.

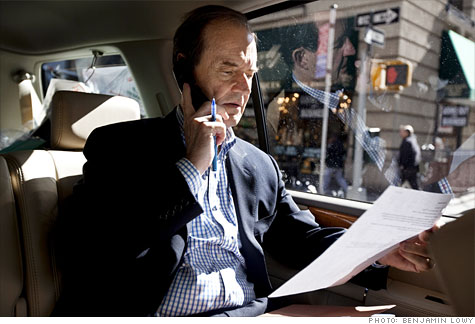

He still does. As he nears 70 -- with an annual haul of more than $10 million -- Boies has never been in higher demand. Plaintiffs in the gargantuan BP (BP) oil-spill litigation want him to be their champion; a judge will decide who gets the plum job as lead counsel. He recently sued Google (GOOG, Fortune 500) on Oracle's (ORCL, Fortune 500) behalf in an important test case about copyrights and patents in Silicon Valley. Between now and Christmas, Boies has three more trials lined up: He'll be representing Guy Hands and the British private equity firm Terra Firma against Citigroup (C, Fortune 500) over the billion-dollar auction of the music company EMI; Merck (MRK, Fortune 500) and Schering-Plough in a billion-dollar breach-of-contract arbitration; and Oracle against SAP in another billion-dollar intellectual-property quarrel. Then there's the same-sex marriage case in California that's on a possible fast track to the U.S. Supreme Court, and a divorce spectacle involving control of the Los Angeles Dodgers. It's no wonder Charlie Rose once asked Boies, "Are you involved in every important case in America?"

His close friend and a current law partner, James Fox Miller, compares Boies to a peerless brain surgeon. "There are many patients with complicated brain tumors, and there's one doctor in the world who knows how to remove them," he says. "David's like that -- with the most difficult legal cases. He moves from one to the next to the next." There's not much handholding -- sometimes Boies swoops in just before a court date, and you'll be disappointed if you want your calls returned immediately.

Even so, for 44 years, clients have sought his counsel because of the results he gets. Understanding his colorful history and record explains why it's been said that each generation discovers Boies anew. Clients come to appreciate that he ignores orthodoxy. Unlike many trial lawyers, he wanders in and out of specialties. He's happy to represent either side in a dispute -- saving a company from financial ruin or suing one into it. And he'll work on a contingency basis if a case looks sweet enough. In fact, his 240-lawyer firm -- Boies Schiller & Flexner -- has revolutionized the economics of corporate law practice by pulling away from a billable-hour model. Boies Schiller builds incentives into billing, so value is based on results rather than merely time put in. According to The American Lawyer magazine, among large firms Boies Schiller has the nation's third-highest profits per equity partner -- $2.9 million, even better than those of Cravath.

Boies excels in the courtroom by going against convention. He's hypercompetitive, yet many foes adore him. He's Manhattan urbane, yet Midwestern soft-spoken -- juries think of him as an Everyman who resembles Bill Murray. Boies works hard, yet once got ready for a trial by reading documents for two straight weeks while sitting in a box at the U.S. Open. He is obsessively prepared, yet instinctive on his feet -- when making an argument in court, he doesn't use notes, which makes him seem like the consummate listener. "David doesn't shout or try to win by overwhelming the opposition by noise," says Maurice "Hank" Greenberg, the former CEO of AIG (AIG, Fortune 500), whom Boies successfully defended against AIG's claims of financial irregularities.

Above all, Boies is a storyteller. "Nobody is better able to describe the gist of a case," says Ted Olson, a friend and his opponent in Bush v. Gore a decade ago. "He has a sixth sense of how to be persuasive. People instantly like David -- he's not a bore at the dinner table."

Though not the introspective type, Boies acknowledges his ability to cut to the chase in jargon-infused litigation. "It is easy to be accurate if you have the freedom to be complicated, and it is very easy to be simple if you have the freedom to shade the truth," he says. "What's hard is to be simple and very accurate, and that takes work to figure out what are the simple truths that are going to sustain your case."

In his array of clients, Boies displays few ideological agendas. Instead, it's all about him and winning. He's happy to admit it. While he wouldn't have represented George W. Bush instead of Gore, he probably would have defended Microsoft (MSFT, Fortune 500) on antitrust charges rather than prosecuted it if the company had called with a retainer first. He is engaged in no crusades to fix the world, but he does believe in the process of litigation and his own primacy in it. "I like cases where the stakes are high and the issues are important," he says. It doesn't hurt if "public interest is high" too. As he knows well, that "correlates into press interest." He likes press interest. For years it was so good he didn't even need a PR person.

He knows how to cultivate an audience. Ever since Cravath, he's worn a frugal Sears (SHLD, Fortune 500) or Lands' End navy-blue suit. He now has 15 of them -- ordered right from the mail-order catalogue. They go nicely with the blue knit ties, circa 1972. For those wild-and-crazy days, he's got a gray Lands' End suit.

Corporate lawyers do Brooks Brothers, so what's with the off-the-rack clothing? Boies says he wears the same clothes to work every day because "it goes with everything I have." But that's a bit too clever. The ties in extended jury trials, for example, are nothing if not thought out. "Juries notice everything," Boies says. During his years defending IBM (IBM, Fortune 500) in antitrust cases, he "found that juries would fixate on the fact that I was not changing my tie. And they'd tell me afterward they had long debates about why I didn't. There was a faction of men who thought 'Well, Mr. Boies is just so dedicated to the law that he didn't care about his wardrobe.' But you had the faction of women who said, 'Oh no, big corporations don't hire anybody except very fancy lawyers -- and he's just putting that tie on to make us think he's an ordinary person.' So I decided ever since that the more conservative approach was to wear not just different-colored knit ties, but different ties altogether." Whew! Imagine, then, the cogitation that goes into the substantive groundwork for a complex trial.

David Boies had a colorful path to the law. The son of schoolteachers and the oldest of five children, he grew up in Illinois farm country and then Southern California. As a dyslexic, he didn't learn to read until third grade, yet he became a champion debater -- quick on his feet, adroit with words, without need of index cards (which he'd be too slow at reading anyway). At 18, he married his first wife, Caryl Elwell, who was a year younger -- they told their parents they were going to the school dance but eloped to Mexico for a few hours instead -- and had a child 11 months later. After working for two years, he attended the University of Redlands in Southern California -- he also had a job teaching journalism to the patients at a state hospital for the criminally insane -- but he was accepted at Northwestern law school early, and he got his undergraduate degree there as well.

He didn't receive his J.D. from Northwestern, though. His marriage didn't last, and Caryl got a divorce in Nevada after four years, taking their two young children with her. While Boies was at the top of his class, his legacy was getting exiled -- for having an affair with a classmate, Judith Daynard, who happened to be the wife of his evidence professor. Oops. Northwestern helped him get into Yale, and he and Daynard -- who transferred to Columbia -- got married before graduation.

Boies aimed to teach law. Still, when in 1966 he was offered a $9,000-a-year job at Cravath, he took it, quickly establishing himself as an eccentric. Cravath was the quintessential white-shoe firm, but Boies traipsed around in black leather sneakers. To the consternation of some partners, he took off an entire summer to do civil rights work in Mississippi. After three years Boies was about to leave for a teaching position at Stanford, but partner Tom Barr persuaded him to stay on to defend IBM from a suit initiated by the U.S. Justice Department. "This is going to be the most important antitrust case since Standard Oil," Barr told him.

Boies demonstrated why Barr wanted him. Boies was intuitive and resolute -- his cross-examination of the government's culminating witness, an economist, went on for 38 days. Cravath rewarded him with coveted partner rank in less than seven years. Then he got lucky. In 1976, Barr -- still consumed by the seven-year IBM saga with the Justice Department -- needed someone to decamp to Los Angeles to be lead trial counsel in CalComp v. IBM, the largest of the civil IBM cases. At the time, CalComp was the largest private antitrust case ever brought, with IBM facing damages of $400 million. At 34, Boies was young to be given such responsibility. CalComp would be the first milestone in his career. In a three-month proceeding -- involving 500 exhibits and 11,000 pages of transcript -- his preparation, combined with phenomenal recall of details, enabled him to persuade the judge to dismiss the suit even before it went to the jury.

Barr had taught Boies that on cross-examination you had to know every word a witness had uttered on a relevant topic, the better to hoist the witness by his own petard. In the days before search commands on a PC, it took months of digging to collect a witness's words. Cravath had limitless resources, and those words would be assembled by legions of paralegals in famed "Cravath binders." Barr was accomplished at using them. What Boies added was a flair for the theatrical and the knack to make it seem effortless.

Before the trial began, Boies had been shopping in L.A. for night-lights his kids used when visiting. Boies noticed the night-lights were made by CalComp. In his opening to the jury, half of Boies's counsel table was covered with Mickey Mouse night-lights and other novelties; on the other half of the table were IBM electronics products that CalComp was complaining about, with the covers removed to show the circuitry inside. This, Boies explained, was the dispute in a nutshell: IBM manufactured worthy machines, while CalComp made junk, seeking to gain in court what it lacked in old-fashioned creativity. It was an elegant, damning statement of the case -- born of serendipity at a hardware store.

In his spare time, Boies co-wrote an academic treatise on regulation. A confidant of Ted Kennedy's noticed it and recommended in 1977 that the senator hire him as a staff lawyer. (The confidant was Harvard professor Stephen Breyer, now a Supreme Court justice.) In giving up Cravath -- as, perhaps, in letting his first marriage go south, behaving recklessly at Northwestern, and then failing at the second marriage, to Daynard -- Boies had revealed a willingness to take risks, and maybe a fascination with it. He even took a pay cut of roughly 80%. "My total Senate salary covered my alimony payments," Boies says.

After two years on Capitol Hill, he went back to Cravath in late 1979. Eventually following him to New York was Mary McInnis, a White House domestic-policy adviser Boies had bonded with over romantic antitrust talk. Nine years younger than Boies, she would become his third, and enduring, wife in 1982.

The month after their wedding, Boies got the case that would endear him to the media evermore. Westmoreland, the commander in Vietnam, had sued CBS (CBS, Fortune 500) for $120 million over a documentary alleging Westmoreland had deceived the public by understating the military strength of the enemy. Boies had never handled a libel case and had done little First Amendment work. A couple of years of discovery changed that. Mary Boies got good at standing up for her new husband. "Don't worry," she would quip, "it's a short amendment."

With characteristic meticulousness, Boies and the Cravath squadron outflanked the opposition so badly over four months of trial that Westmoreland surrendered in early 1985. Boies's cross-examinations were so biting that newspaper reporters in the gallery started humming the theme from Jaws when he got up to question a witness. He shredded Westmoreland's credibility. The technique was to continually point out inconsistencies between what Westmoreland was saying in court and what he'd said before. "What you do," Boies says, "is set it up so you get the jury to think he's lying -- before you even suggest he's lying."

The federal judge who presided, Pierre Leval, remembers Boies's craftiness. Early on, Leval had ordered both sides to deliver briefs on a motion to his Manhattan apartment on a Sunday evening. Westmoreland's lawyers left their papers with the doorman. The CBS brief arrived soon thereafter, but the doorman called the judge to say the messenger wanted to deliver it personally. "I opened the door and there's David Boies in a torn sweater," Leval tells Fortune, 25 years later. "I thought to myself, 'How many Cravath partners would do that?' I thought that was very smart -- and I apparently haven't forgotten it."

Boies says the trial was formative, teaching him "to be patient with witnesses and to concentrate on only a few points." Most stories about Boies claim he has a photographic memory. He says he doesn't. Rather, he's skilled at "figuring out what's important" for a jury or judge to understand -- and then fixating on it. Dyslexia may actually help, as it forces him when he's poring over documents to remember only what's in fact crucial or what he thinks will be; either way, he winds up with a condensed narrative of a dispute.

In the process of simplifying, though, Boies puts himself and those around him through the wringer. It is just one of the contradictions about Boies that those who've worked with him regularly grumble about his relentlessness. During the Microsoft case he uttered a famous, or infamous, line. One late night, his legal team was exhausted and wanted a break. Boies would have none of it. "Do you want to win -- or do you want to sleep?" he asked them. They put the line up as a screensaver on their PCs.

Eighteen months after Westmoreland, Boies was in Charleston, S.C., on business. Westmoreland lived there, and Boies ran into him on the street. They exchanged pleasantries. Then they talked briefly about the libel suit. Westmoreland told Boies, "I wish you had been my lawyer."

Westmoreland v. CBS turned Boies into a celebrity. The Four Seasons has a table for him in Midtown Manhattan; the casinos in Las Vegas can't wait until he next visits to play craps for a weekend. Companies in distress aren't immune to the lure of the marquee. Boies says he often gets involved in litigations "when something's already gone wrong" and a company's looking to alter course. So, after Texaco in 1985 lost a $15 billion judgment to Pennzoil -- then the largest award ever and a figure six times Texaco's market capitalization -- Texaco turned to Boies. He made it to the Supreme Court but lost, and in a settlement Texaco had to pay Pennzoil $3 billion.

Nonetheless, before he was 47, Boies had had three bet-your-company defenses -- IBM, CBS, and Texaco -- and achieved two smashing victories. He had become the Clarence Darrow of the Fortune 500.

He settled back into Cravath for the next decade. He loved litigation, for the same reasons he loved craps. Both were mathematical games of a sort. You had to take risks, yet "manage your exposure." There was an intellectualism to it. And you got an outcome each time -- each game ended, with a winner and a loser. Boies liked that. He wasn't a person to ruminate -- not on cases, mistakes, people left behind.

By his own account he was earning multimillions and made no apologies about his place in the food chain. "Everybody's entitled to a lawyer, but not everybody is entitled to me," he says. He bought a 78-foot sloop and led family cycling expeditions through the south of France. And then, in 1997, suddenly and permanently, he left Cravath, which partners never did, unless it was in a mahogany box.

The precipitating event was a dispute with the partnership over his decision to represent George Steinbrenner and the New York Yankees. But the split had been long simmering. While he'd been there the better part of 30 years, he never quite fit into the Cravath universe. Its partners were preternaturally cautious and mainstream -- they didn't know the best casinos in Monte Carlo, nor had they dated the wife of one of their law professors. Boies flourished at Cravath despite being a rebel and a headline hog. The New York Times covered his resignation on the front page.

Boies initially set up shop in Mary's small law office. (The independent firms of his wife and his son David III have had clients related to Boies Schiller cases -- and Boies has been criticized for involving his children's businesses in his own firm's work. Two of his other children work at Boies Schiller, as does his second wife, Judy.) Jonathan Schiller, his co-counsel in the Yankees mess, quit Kaye Scholer and joined him -- and soon Boies Schiller had offices in Westchester and Manhattan.

In this second act, Boies now took on one big case after another that would raise his profile further. First up was U.S. v. Microsoft, in which he'd do the signal cross-examination of his career.

Joel Klein, the antitrust chief at Bill Clinton's Justice Department, wanted Boies to prosecute the case from the outset. It was a politically surprising move to hire the man who helped beat the government in the IBM case. But Klein understood that Boies knew the game from the defense side and would be well equipped to parry Microsoft.

There were risks for Boies -- Microsoft was a much-lionized company, he was busy with his own budding business, the government would pay him a paltry hourly rate -- but he decided it was too exciting a trial to pass up. This was Westmoreland all over again: a cultural icon in the dock, a case that would consume the press. Boies relished the opportunity to duel Bill Gates, if only to test the power of cross-examination applied against someone with Gates' bandwidth. Gates proved to be no match. Boies pounced on him during 20 hours of stonewalling, but with agility rather than ferociousness.

Instead of mocking Gates, Boies gave him the room to bury himself. Some winning cross-examinations end with one mortal blow. Most succeed by 1,000 cuts, without the victim's even realizing it. In one absurd exchange, Boies showed Gates an e-mail in which Gates had typed "Importance: High."

"No," Gates interrupted.

Boies was on his way to a different point, and lesser lawyers would not have recognized a gift. Boies did. "No?" he asked incredulously.

"No, I didn't type that."

"Who typed 'High'?"

"A computer."

"Why did the computer type in 'High'?"

"It's an attribute of the e-mail."

"And who sets the attribute of the e-mail?"

"Usually the sender sets the attribute."

They jousted a few more rounds. And then Boies asked, "Now, did you send this message?"

Replied Gates, unbelievably: "I don't remember doing so."

Evan Chesler, Boies's former Cravath partner, likens him in a trial to a GPS navigation device. "It knows how to get from Point A to Point B, but if you alter direction, it takes time for the gadget to 'recalculate,' " Chesler says. "David always knows the destination, and he has the ability to seamlessly recalculate the route."

While Gates largely won the four-year war with the Justice Department -- under the control of the new Bush administration, in late 2001 it settled on terms favorable to Microsoft -- Boies walked away the folk hero who had embarrassed the smart-aleck boy king.

As Microsoft wound down, Boies took on the case -- a defeat -- that will lead his obituary, Bush v. Gore. His performance at the Supreme Court was less than electrifying. Boies failed to cast the issues in broad historical or political strokes. He didn't sound as constitutionally fluent as Laurence Tribe, the Harvard law professor who argued the case the first time it came before the Supremes only weeks earlier. Boies lost, yet this case burnished his standing just as Microsoft had. His courtroom work in Florida had produced the victories that initiated the electoral recount. Few thought the Supreme Court would reach out to stop it. When Al Gore asked Boies to argue the case in Washington, Boies was being asked to take a bullet. Anybody in Boies's sneakers was destined to fail in Bush v. Gore.

Although U.S. v. Microsoft and Bush v. Gore landed Boies on the evening news, they didn't fill the coffers at Boies Schiller. Lucre wasn't the reason Boies practiced law, but he surely liked the '59 Margaux that came with it.

Unlike Cravath, Boies Schiller held the promise of fantastic legal riches. Though the firm has regular corporate clients to maintain a stream of revenue, one-off assignments make the most rain. On many of these cases, rather than rely chiefly on billable hours -- which not only fail to reward skill but make clients suspicious their lawyers intentionally plod along -- the firm imitates investment banks by charging flat fees. A signing bonus, for example, can be $10 million -- regardless of how much lawyer time actually gets put in.

Boies Schiller says about half its revenue in recent years came from flat fees and contingency arrangements. "We share in the risk of the lawsuit -- and we share in the reward," Boies says. His $960 hourly rate isn't cheap, but it often doesn't accurately measure his value. In a profession of conformity, Boies chose to break away. The gamble flowed from his fondness for rolling the dice in law as in life. "The last roll is always '7,'" Boies tells Miller on occasion, "and you never know when it's going to come up."

In forgoing the certainty of billable hours, the trick was to place smart bets. Two litigations established how adept Boies's firm could be. The first involved a price-fixing class action in 2000 -- representing 130,000 art collectors against Christie's and Sotheby's. The feds were already investigating commissions charged by the auction houses, and there was a feeding frenzy among law firms looking for a piece of the action. To determine a winner, an inventive federal judge set up a blind bidding contest. Each firm had to state a floor amount that victims would receive before lawyers saw a dime; the lawyers would get to keep 25% of the excess.

Most of the 20 competing firms bid between $50 million and $150 million. To their horror, Boies Schiller came in at $405 million. But, incredibly, so did another firm. The judge chose Boies because of his experience. Boies figured if he had to take the case to trial, his maximum out-of-pocket expenses would be $8 million. Instead, as Boies played Christie's and Sotheby's lawyers against one another, the class action settled in seven months for $512 million. Boies and his firm took home just under $27 million -- five times what its normal billing rate would have produced. Preparation and fortuity: Boies analyzed the case correctly but also lucked out, since the other $405 million bid might have prevailed.

Two years ago Boies's firm made its biggest killing of all, resolving American Express's claims that Visa (V, Fortune 500) and MasterCard (MA, Fortune 500) prevented it from competing for bank-issued credit cards. Boies says a confidentiality agreement forbids him from discussing fees, other than to note that the firm put in close to 100,000 hours of lawyer time. The American Lawyer reported the fee exceeded $150 million -- on top of an annual $5 million fee. Other firms hear about that kind of payoff and wonder if billable hours are anachronistic.

With only mild sheepishness, Boies says he takes in "at least double" what he'd be earning at Cravath. When he left 13 years ago, that was $2.5 million. He won't say what he makes now, but a law firm source says it's north of $10 million -- probably making him the highest-paid lawyer in the country who doesn't chase ambulances.

Why, then, does Boies still work so hard? He wouldn't be bored sailing to distant shores, tending his Hawk and Horse Vineyard in Northern California, or entertaining at his $7.5 million pied-à-terre overlooking Central Park. He simply lacks the capacity to stop litigating. When somebody has a high-profile case, he wants it. "It's a good thing David wasn't born a girl," Mary likes to say. "He can't say no."

The game never gets old. "I win virtually every case I should win," he says, "and I win a number of cases that people think I shouldn't." Be it his current representation in the Dodgers divorce of Jamie McCourt -- whom he describes as a damsel in distress rather than just another spouse fighting over who gets the bigger slice of a billion-dollar pie -- or the upcoming Oracle-Google brawl over open-source software -- which he fashions as a struggle of good vs. evil -- Boies revels in the conflict that will determine outcomes. He doesn't just obligatorily believe in the adversarial system -- he feeds on it. Competition is character. He spoiled his six children as they grew up, but he also gave them no quarter when they played Axis & Allies; when it was time to take over the world, Dad won. When son Jonathan at 14 lost a football bet with him, Jonathan had to mow the vast Westchester lawn for a year to pay off the debt.

Notwithstanding the mellow charm, despite the sneakers, Boies in the end is a gladiator. He loves to win, but the fight is half the fun. For David Boies, litigation isn't just a nice meal ticket -- it's a compulsion. For his clients, it can mean deliverance. ![]()

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |