Search News

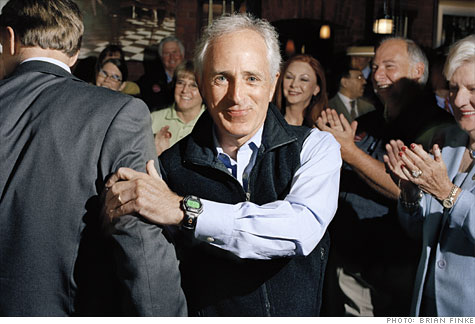

Corker at the Big River Grille & Brewing Works in Chattanooga, where he stumped for gubernatorial candidate Bill Haslam

Corker at the Big River Grille & Brewing Works in Chattanooga, where he stumped for gubernatorial candidate Bill Haslam

FORTUNE -- Confrontation. Gridlock. A nation divided. Conventional wisdom tells us to expect a contentious stalemate in the wake of the 2010 midterm elections. But walk up the steps to the Senate Dirksen Office Building, hang a right, and you'll hear a different message: "I'm going to find Democrats who'll come along," declares Tennessee Republican Bob Corker. The Chattanooga real estate mogul-turned-senator is hoping to cajole folks from across the aisle to embrace his plan to reduce federal spending from 24% to 18% of gross domestic product -- in line with federal revenue.

It's not exactly the kind of program Democrats (even those chastened by their party's recent casualties) are likely to endorse, yet Corker is unbowed. He's a fiscal conservative and unabashed supporter of smaller government, but he's also a pragmatist and consummate dealmaker who has built his professional and political career on negotiating with people who don't always share his views. As President Obama faces new math on Capitol Hill, negotiators like Corker -- in short supply these days -- are key to making progress in solving the nation's fiscal woes, which include a $1.3 trillion deficit. With Democrats holding a slimmer majority in the new Senate, the President can no longer peel off a couple of GOP votes -- as he did on the stimulus and Wall Street reforms -- and call it a day. "I'm invigorated," Corker insists. "We're going to be in a much better position to negotiate things that are centrist in nature."

When it comes to finding good deals across the aisle, Corker is like a heat-seeking missile. He worked closely with outgoing Tennessee Governor Phil Bredesen, a Democrat, to bring pro football to Nashville and Volkswagen's only North American factory to Chattanooga. (Defying a brutal economy, the $1 billion factory starts cranking out sedans in January, bringing 10,000 jobs with it.) Chris Dodd, the outgoing Democratic chair of the Senate Banking Committee, spent the better part of a month on Corker's couch last spring negotiating Wall Street reforms. That bipartisan effort was crushed by the White House, and Corker's role in it cost him political points; one conservative blogger tagged him "Bailout Bob."

But if Corker has a dealmaker's optimism, he also has a politician's sophistication and survival instinct. He backed away from supporting Wall Street reforms (critics might say he flip-flopped) once it became clear that the White House wasn't interested in compromise. He later publicly upbraided the President for failing to work across party lines -- a move that earned him respect from conservatives who didn't cotton to Corker's cozy relationship with Democrat Dodd. Corker "will never make a bad deal," insists Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell.

Cutting deals in any Congress this polarized is treacherous business. Some on the right are calling for Corker's head merely because of a committee vote to move the process forward with a new START nuclear reduction treaty that the Obama administration is pushing. (No matter that other conservatives support the accord, and Corker hasn't committed to support it.) Voters say they want progress and compromise, but the 2010 primaries were littered with bodies of established Republicans such as Utah's Bob Bennett, whose co-sponsorship of a market-driven health insurance bill drew the ire of the Tea Party. Will Corker's zeal for the deal provoke a challenge when he seeks reelection in 2012? Or could his pragmatic and results-oriented approach attract the attention of Republican leaders and, as his friends and supporters hope, earn him a spot on the next presidential ticket?

Not afraid to stick his neck out

'I just want to know," Corker fumed at President Obama earlier this year, "when you get up in the morning and come over here for a lunch meeting like this, how do you reconcile that duplicity?" Corker was seething because Obama had invited himself to a GOP luncheon just days after passing Wall Street reforms over near-unanimous Republican opposition, a move Corker saw as phony, at best.

Corker, it turns out, had stuck his neck out with what had been, by all accounts, a genuine attempt to reach a financial regulatory bill both parties could accept. But the Senate Banking Committee's ranking Republican, a wily Alabaman named Richard Shelby, was none too pleased to see a junior colleague taking such an active role in the process of writing the bill. Scolding the President helped Corker get back in Shelby's good graces. "You're a mean little fucker, aren't you?" the Alabaman drawled at a meeting with the 5-foot 7-inch Corker a few weeks after the incident.

"Interesting man," Shelby says of Corker. "He's been very successful and likes to get things done." Then Shelby's lips curl into a soundless snarl. "But now I think he's been acclimated to the real politics in the Senate." Shelby doesn't quite say it -- and neither do Corker's other Senate colleagues -- but there are hints that Corker was naive in thinking he could cut a deal in an election year, when Democrats would be tempted to cast Republicans as villains allied with Wall Street greed.

Tom Ingram, longtime chief of staff to Tennessee's senior senator, Lamar Alexander, was in Corker's office the day that Dodd called and said he was ending their talks. The two senators had met -- together and alone -- nearly every day for a month. Corker was particularly focused on figuring out ways to liquidate big financial firms without hurting the U.S. economy -- tackling the "too big to fail" conundrum. Corker treated Dodd's news like a wedding engagement called off. "He was more hurt than pissed off," Ingram recalls. "It was like a romantic breakup." (Dodd declined to be interviewed for this story.)

Corker first caught the attention of his colleagues -- and the business community -- late in 2008, his second year in office, when Detroit auto executives came to Washington pleading for $25 billion in federal aid, but without a plan to turn themselves around. Corker bored into the auto executives, including Robert Nardelli, then CEO of Chrysler, for keeping factories open when there was no demand for cars. He wasn't just grandstanding, though. He proposed a set of strict conditions on automakers and unions that, as Obama's car czar Steven Rattner notes in his book, "provided a baseline of expected sacrifices" for federal aid. (Rattner is another Democrat who became a Corker pal; the two bonded over a dinner at a Mexican restaurant during the bailout proceedings.) The son of a DuPont (DD, Fortune 500) engineer, Corker is not an intellectual -- you don't see the shelves of biographies and histories that fill other lawmaker's homes. But he throws himself into complex issues with abandon -- reading everything he can get his hands on, quizzing analysts, think-tankers, regulators. On Wall Street reform "he was the most well-informed person on our side of the aisle -- probably on both sides of the aisle," says retiring Sen. Judd Gregg of New Hampshire. "He's knowledgeable because he works at it. Issues like this are so complex that he can have a lot of impact."

But inside the clubby Senate halls, Corker's intense personality -- with all of that relentlessness and tell-it-like-it-is candor -- can also be a turnoff. Years ago, when Corker asked his wife, Elizabeth, out on a first date, she hesitated. "If I have time," he replied, "you have time." She went, and the couple now have two grown daughters. He also frustrates colleagues and critics with actions that look like he's working hard to thread the needle: He initially supported TARP but voted against releasing a second $350 billion chunk, complaining that the taxpayer bailout was being applied in an "ad hoc" way. And the spending cap he is now peddling invites criticism that it enables Corker to appear tough -- even while kicking the can down the road on controversial decisions about precise government cuts he would support.

Starting small with big luck

Corker will be the first one to tell you he's caught some lucky breaks in life. He studied industrial management at the University of Tennessee but was bitten by the construction bug early. His first break came a year out of college when his boss at a development company was transferred and, at age 23, Corker was put in charge of building a major shopping mall in Sarasota. By age 25 he had started his own construction firm with $8,000 he had saved from bonus money earned bringing projects in on time and under budget. His firm, Bencor, started small -- paving drive-ins for Krystal burgers stands and the like -- but soon was riding the '80s Southern construction boom.

Corker's luck held out, barely this time, when he sold his construction company to launch into commercial development. It was 1990, on the cusp of a real estate crash. Corker, then 37, had bought a major downtown office building and within months was leaking cash. "I had to wake up every day and smile and act like nothing was wrong," he recalls. Within 18 months, he'd gotten his financial feet on the ground. (He eventually amassed a fortune -- his net worth is an estimated $40 million to $50 million, making him one of the few self-made millionaires in the Senate.)

By then he was also deeply involved in civic affairs, heading an affordable housing initiative called Chattanooga Neighborhood Enterprise -- the outgrowth of a church mission trip to Haiti to build houses. In 1994, Corker ran for the U.S. Senate but lost in the primary to Bill Frist (Frist, who labeled Corker "pond scum," has since become a friend).

Republican Governor Don Sundquist then tapped Corker to become the state's chief financial officer. Corker got close to Nashville Mayor Bredesen while the pair worked to lure the NFL's Houston Oilers to town. That Corker was helping a rising-star Democrat land a major victory did not go over well inside the Republican administration.

But the friendship deepened over regular buffalo burgers at the Nashville outpost of Ted's Montana Grill. And when Bredesen again ran for governor in 2002, Corker ruffled some GOP feathers by agreeing to open his home to the Democrat to meet local -- and mostly Republican -- business executives. "It was tremendously helpful for me," says Bredesen. "If you're going to be elected governor of Tennessee, you need Republicans and independents. He got some heat over it. But he knew exactly what he was doing."

Corker was reluctant to seek public office again. A different Democrat, Chattanooga Mayor Jon Kinsey, persuaded Corker to run for his job. It proved to be the perfect marriage of Corker's twin passions, real estate development and politics. After he took office in 2001, he applied his dealmaking prowess to revitalizing the city, urging local business owners to open their wallets for $120 million and deploying land swaps to create a community-friendly space. And although some critics questioned the merger of Corker's downtown financial interests with his mayoral duties, he left office a popular figure. The streets were alive; new hotels had opened despite a tax on them; and tenants were filling downtown housing that ranged from the affordable to million-dollar penthouses.

In 2006 he mounted a second U.S. Senate campaign, this time against Congressman Harold Ford. The race garnered national attention not because Corker financed part of the campaign with $4 million of his own money but because of a tacky advertisement the Republican National Committee ran on Corker's behalf. The ad was denounced as racist. Corker insists that he was furious at the RNC and that his polls dropped as a result of it, but Ford remains peeved and writes off Corker as "wealthy and arrogant" in his new book. (Read Ford's thoughts on the midterm elections here.)

Corker's victory made him the only new Republican senator elected in a year of Democratic triumphs. But the campaign also put a temporary strain on the friendship with Bredesen, who appeared in ads on behalf of Ford. "It was very, very difficult" to campaign against Corker, says Bredesen, even though "I liked [Ford] and wanted to support him."

Bringing VW to to Tennessee

To understand why Bob Corker thinks he can cut deals -- actually get stuff done -- in hyperpartisan Washington, it's helpful to revisit a scene that unfolded on the veranda of his 1927 Tudor mansion one evening in 2008. VW executives were the guests of honor at a dinner of venison and fine wines. The hosts included Bredesen, Sen. Lamar Alexander, and County Mayor Claude Ramsey. The auto executives, shopping for a site for their first North American factory, were eyeing a 500-acre parcel of land about 20 minutes from Chattanooga's downtown. For years Corker -- at some political cost -- had refused to divvy up the acreage for smaller potential employers, hoping for just this moment. But the Germans noisily complained (Corker loves German candor) that the site of a former munitions plant was so densely wooded it was difficult to assess. The next morning they would be boarding a plane to look at a competing state, Alabama.

That same night Corker and his fellow Tennessee officials decided to bet the bank: By the time the VW executives were in the air they had contracted every city, county, and private heavy-equipment operator available. Within weeks the site was cleared of trees. A few weeks later Corker got the call: VW would be building its factory in his hometown. (It also helped that the localities offered a $577 million tax-incentive offer, topping Alabama's bid.)

To be sure, local politics is always less partisan than national: Combining forces to lure a foreign automaker is much easier than bridging the deep philosophical differences on the role of government that Corker's proposed spending cap is sure to stir.

But Corker's alliance with Democrats like Bredesen -- despite the political risks -- is the kind of starting point that most Americans claim they want to see out of Washington. "In politics, where there's a lot of posturing, he's unusual," says Bredesen, who, like Corker, built a company before going into politics. "He closes the door and deals with you, very businesslike." The outgoing governor adds: "There are lots of people who are reasonable Republicans and Democrats, and when the economy comes back, the anger will subside."

Despite his failed attempts at bipartisanship on the Hill, Corker remains convinced that the impending debt crisis will bring both sides together -- at least partway. He's been traveling across Tennessee with a presentation showing how his proposed federal spending cuts will help avert crisis. "People, regardless of their politics, leave in a very somber mood when they see how we're in danger of losing our American exceptionalism."

As he makes his case for government belt-tightening, Corker can't help but invoke another Democrat, Erskine Bowles, Democratic co-chair of the President's debt commission, who has proposed eventually cutting spending to 21% of GDP. It is as though he's congenitally predisposed to cross party lines. Then again, if things don't go his way, Corker's also capable of plowing down any trees that get in his way. ![]()

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |