Search News

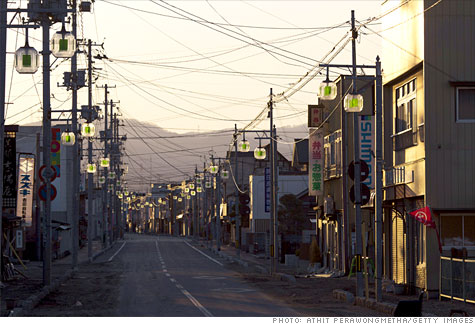

A street sits deserted in Minamisoma, Japan, 12 miles from the Fukushima power plant.

A street sits deserted in Minamisoma, Japan, 12 miles from the Fukushima power plant.

FORTUNE -- In ordinary times, Minamisoma ("south" Minami) is a bustling little city of about 71,000 that sits along the Pacific coast line in Japan's Fukushima prefecture, about 150 miles north of Tokyo.

Most of the town's citizens used to work in the small shops and businesses that line its streets -- beauty parlors and banks, small restaurants and coffee shops, fast food joints, a bakery and a couple of big supermarkets. There are a couple of large factories -- a plant that makes kitchen appliances is one of the largest employers in town, and there's a Hitachi Denshi factory that makes electronics for the auto industry. But small business is the town's economic lifeblood.

It's as ordinary a Japanese town as you could find, except for one fact: these days, small or large, all the businesses have one thing in common: they're closed. Ride through the Minamisoma's main streets today, and you'll see shades drawn in the windows of nearly all the small businesses.

These are not, needless to say, ordinary times. Minamisoma today is a place where the simple act of paying a cab fare reduces the driver to tears. The city, at its closest point, lies just 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) north of the stricken Fukushima Dai-Ichi power plant that is now the site of the worst nuclear crisis since Chernobyl. As such, the town sits at the geographic core of what's become a strange, nuclear never-never land: for nearly three weeks now, the Japanese government's "guidance'' to those living 20 to 30 kilometers away from the Fukushima Dai-Ichi reactors is that they can remain in town should they so choose, but they should stay indoors or else risk exposure to radioactive gases.

As such, to cruise through Minamisoma, as I did this past weekend with a colleague, Tokyo-based freelance reporter Hideko Takayama, is to visit a nuclear ghost town. Radioactivity levels at 8am Saturday, according to the local government, were completely normal, so we decided to venture in. The town's mayor, Katsunobu Sakurai, had actually issued a plea on YouTube for reporters to come and see for themselves the devastating impact the ongoing nuclear crisis is having on his little city.

For block after block, there are no pedestrians on the streets, and only a few cars in transit. A couple of stray dogs roam, looking desperately for food. The small merchants whose stores and shops comprise the commercial heart of this little city are, needless to say, getting crushed. Yuichi, the taxi driver who agreed to ferry us around, works for a small company that has a fleet of four cars and usually takes in about 45,000 to 50,000 yen a day ($550-$610). Yesterday, he says, the four taxis had one fare between them. It came to 680 yen ($8.30).

The commercial center of Minamisoma lies far enough away from the ocean (about four miles) that, physically, at least, it survived the tsunami. That is not true of the residential areas closer to the coast, where the destruction, as in town after town up and down the coast, from Iwate prefecture in the North down through Fukushima in the South, is all but indescribable.

Tallying the damage

Just how destructive the tsunami was to this particular town becomes very specific when we get to city hall, the only place in town where there is any sign of life. There, Minamisoma's political leaders and bureaucrats try to cope amidst the chaos and fear. A few residents whose houses or apartments have been destroyed troop in to fill out the paperwork recording that they are now homeless (even amidst a catastrophe of biblical proportions, bureaucracy grinds on). Upstairs, just outside the Mayor's office, there is a sign with the up-to-date statistics: as of late Saturday afternoon, there were 301 confirmed deaths from the tsunami, 1173 people were "missing" (and, though officialdom still won't say so publicly, presumed dead), and 1800 houses had been destroyed.

Up on the third floor, where Mayor Sukurai's office is, city officials take updates from search and rescue teams hunting for bodies, try to coordinate getting supplies of food and water to the evacuation centers outside the city where many of its residents are now holed up, and keep track, minute-by-minute, of the activity at the TEPCO nuclear plant, which is not visible from the town hall, but is uppermost in their minds.

The Mayor is meeting with a rescue crew, so we sit down with his chief aide, a man named Sadayasu Abe, who has worked for the Minamisoma government for more than 30 years. Most of his colleagues are wearing the little white cotton facemasks that cover the nose and mouth, a commonplace in Japan during the allergy and flu seasons. But, Abe concedes, that's not why they're wearing them now. "They're worried about radiation," he acknowledges.

The facemasks are a security blanket, something that provides the illusion of increased safety. Millions of people as far south as Tokyo are wearing them these days in Japan, and not because they're worried about getting the flu. But the idea that they help protect anyone from exposure to radioactive gases is, of course, a joke. Abe himself doesn't bother wearing one.

He tells us that of the town's 71,000 residents about 50,000 have left, since the national government said it's okay to stay, but only indoors. For elderly people in particular, Abe says, this edict was untenable; "how were they to get anything to eat if they can t go out to shop?"

After a while the town began running buses to supermarkets outside the 30-kilometer zone, but the majority of people chose to get out anyway. They're either staying with relatives elsewhere in Japan, or are holed up in one of the many evacuation centers set up to house those affected by the quake/tsunami/nuclear crisis. They can come back at any time, Abe says, and a few have started to trickle back into town. But most continue to stay away, unsure when -- if ever -- it will be safe enough to return and live anything resembling a normal life.

Lack of preparedness

Abe, not surprisingly, looks exhausted, and like all Japanese, he has the politeness gene. But it also becomes clear, as we talk, that he is angry. He's angry at Tokyo Electric Power, and he's angry at the national government. At no point in the 30 years he has worked for the city, he says, did TEPCO or the government say it would be a good idea to prepare for a possible nuclear emergency. No evacuation drills, no town hall meetings to discuss what residents might do should the unthinkable happen. Nothing.

"Nothing?" I ask him again. How can that be so? This is an earthquake zone -- everyone knew that -- and earthquakes cause tsunamis, and the plant sits right along the coast. And this is Japan, a nation that pays attention to detail, whose people famously follow instructions, who...

He interrupts me, and through gritted teeth says, "Nothing. Nothing. We never received any guidance or instruction from them." He's boiling.

What about towns closer in, did they have drills? "I think some did, I'm not sure," he says. (In fact, earlier in the week, at an evacuation center farther south, I spoke to a city official from the small town of Futaba, which literally sits in the shadow of Fukushima Dai-Ichi. He says that once a year the residents of the town would go to a local gymnasium, where they would be instructed on "how to use a fire extinguisher.") The townspeople of Minamisoma occasionally had fire drills, but never was there any preparation for a nuclear accident. "There was never any communication from TEPCO that something like what's happening now was even possible," he sighs.

As we make our way out of the building, there's an odd moment of comic relief. In the main lobby on the first floor I see a foreigner wearing what looks to be a Hazmat suit: he's in white from head to toe, a hood on his head and little white booties on his feet. Who the hell is this, I wonder? One of the nuclear engineers France has sent to help try to contain the damage at Fukushima? Has this guy actually been inside the plant? I need to talk to him.

We make eye contact and approach each other. He's not a nuclear worker at all. It turns out he's a Tokyo-based television journalist. He, too, has come to interview the Mayor. I finger the material of the suit, and it feels like cotton. I realize there's no way this is a Hazmat suit, which are usually made of rubber, or a plastic synthetic, or some combination thereof. "Does this help?" I ask him, a bit skeptically. Oh yes, he insists, of course.

Then, as if on cue, a forlorn-looking cameraman comes trudging through the entrance of the town hall. He's wearing jeans and a light jacket. There's little in life more preposterous than a TV journalist trying to draw attention to himself in a war/catastrophe zone. I try not to laugh. For some reason all I can think of at that moment is a line from Woody Allen's classic film Annie Hall. Allen's character has flown out to Los Angeles, and his friend Max (played by Tony Roberts) picks him up at the airport... dressed in a Hazmat suit. As Roberts pulls the hood and visor down over his eyes as they get in the car, Allen stares at him. "Are we driving through plutonium, Max...?"

I desperately want to repeat that to the TV guy, except then it occurs to me. Who the hell knows? Maybe the day's atmospheric readings are wrong. Maybe we are driving through plutonium. In which case we probably all should have been wearing real Hazmat suits.

The lone lunch counter

We had asked Yuichi the cab driver to see, while we were interviewing the city officials, if there was anyplace in the vicinity to get a cup of coffee and a sandwich before pushing on. He excitedly tells us as we come out that in fact, there's one coffee shop in the city itself that's actually open. This we have to see.

The Ikoi Coffee Shop (it means "relaxation") sits near the center of town; the street it's on is deserted, save for the presence of yet another roaming dog. When we enter, there are two customers present -- one, an older man, sits at the counter having a coffee. At one of the tables, sitting by herself, is an elderly woman, eating lunch. Also present are the owner of the café, Yoshitomo Yoshida, and his wife. These are the only four civilians we've seen out and about in the nuclear Ghost Town. I ask Yoshida, 71, why in the world his shop is open when the government is politely but firmly suggesting that anyone who decides to remain in town should stay indoors.

He says he and his wife originally got out entirely. "We stayed at an evacuation center well outside of town. We got there on Wednesday, the 16th, the day after [Japanese prime minister Naoto] Kan went on TV and said the nuclear problem was going to get worse." They stayed for a couple of weeks. But Yoshida couldn't stand it. "There is absolutely nothing to do there. I just got bored out of my mind,'' he says. "Plus, we had left our dog at home. We had no idea this would drag on so long. Neither the government nor TEPCO gave us any indication of how long it would take to fix the nuclear plant. I began to get afraid our dog would starve to death. So we came back on the 31st."

The next day, he said, he decided to open his shop. "We'll stay unless the radiation readings get really bad," he says. "I figured, why not open the shop? Maybe I'll get some customers.''

One of his customers this day is 83-year old Sumiko Oya, who sits in the booth in front of us, eating fish stewed in soy sauce and smoking a cigarette. (The fish come from a local market but had been bought and frozen before radiation started leaking into the sea from the Fukushima Dai-Ichi reactor.)

Oya is wearing a green jacket with a big gold broach, a stylish black pillbox hat, and has tastefully applied both makeup and lipstick. Here, in the middle of Minamisoma, amidst an ongoing nuclear drama, is an elderly woman who has dressed up as if for a night on the town.

Or, in this case, a day on the town. We ask her the same question: what on earth are you doing here? She laughs, stubs out a cigarette and lights up another. "I don't give a damn what the government says," she says. "I'm 83 years old, what do I have to be afraid of? What, that I might get cancer ten years from now if I stay here?" She laughs again, this time ever harder. We all do. It's a fair point.

She lives just five minutes from the coffee shop -- a place where she is used to coming almost every day for lunch. She had stayed in her apartment after the tsunami and the nuclear accident. "My daughter lives up in Hokkaido, and she was yelling at me to come up there and stay with her. But it's too snowy there. We never get any snow down here. I like that."

How did she feed herself for the past three weeks? "I don't eat a lot, and I had enough food stored at home to get by these past few weeks." I ask if she had walked to the coffee shop that day.

She looks insulted. "Of course not! I drove. What? Do you think because I'm 83 that I can't drive?" What of her friends, did they leave, or did some stay, like her? "I just called one of my neighbors who I hadn't seen in a couple of weeks. I said, `where are you?' She said, `I'm in an evacuation center in Niigatta [a city more than 100 miles due west, on the opposite coast of Japan].' I said, 'what the hell are you doing there!?' And she yells back at me, 'what the hell are YOU still doing in Minamisoma?'"

Oya laughs again. "You know, my husband and I -- he died a few years ago -- we came here because of the climate. We liked it here. I still do. I'm not going to leave."

A cab ride to remember

We pay the bill and leave. I ask our driver, Yuichi, to take us to the closest point we can get to the 20-kilometer no-go zone. He drives through the empty streets of town and eventually gets on a four lane open road, heading straight for the coast and the Fukushima reactors. But at 20 kilometers almost exactly, the road is blocked off. Not with barriers of any kind. Not with Japan Self Defense Forces, or national or local police waving us down. (There is, make no mistake, NO ONE around.)

Preventing us (and anyone) from proceeding any farther is but one thin strip of police tape, stretched from one side of the road to the other. There isn't even a sign of any sort, no scary looking skull like on a can of rat poison. It's as if they had cordoned off a crime scene -- and then got the hell out of dodge. It would have been easy enough to just cut the tape and drive on.

We wanted no part of that. Yuichi heads for the mountains to the west, then due south, where Takayama and I and are due for another interview late that afternoon, well out of the nuclear zone. When we arrive at our destination, we settle up with Yuicihi. We pay him 34,000 yen for the day's work. He takes the money -- by far his first decent fare in three weeks -- and thanks us.

And that's when, just before heading back to Minamisoma, his home, tears well up in Yuichi's eyes, and he begins to cry. ![]()

| Overnight Avg Rate | Latest | Change | Last Week |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 yr fixed | 3.80% | 3.88% | |

| 15 yr fixed | 3.20% | 3.23% | |

| 5/1 ARM | 3.84% | 3.88% | |

| 30 yr refi | 3.82% | 3.93% | |

| 15 yr refi | 3.20% | 3.23% |

Today's featured rates:

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |