Search News

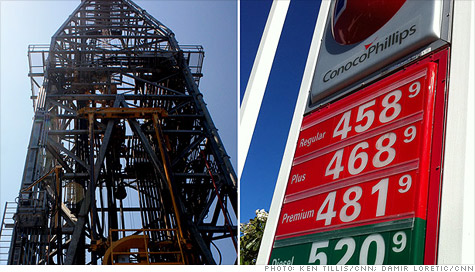

FORTUNE -- At first glance, it seems like a great time to buy a refinery. The price of gas is hovering around $4 and will likely stay high heading into the summer months. (Even news of Osama bin Laden's death hasn't moved prices much.) But a closer look shows refiners are actually trapped between two sets of players in the oil industry -- providers who deliver crude oil to them for refining, and customers who buy their finished products.

Crude providers are contending with global macroeconomic forces that make the price of their raw materials high, and customers of course want to buy the finished petroleum-based products as cheaply as they can. Refiners thus find their profits squeezed from both sides. However, refining is still an essential part of the oil industry -- a barrel of unrefined crude, after all, won't fill your gas tank.

So while it's unusual that BP (BP) wants to get rid of its top refinery in Texas City, Texas, it's altogether strange that the company can't seem to find a buyer. The refinery, after all, can crank out more than 430,000 barrels of refined petroleum product per day. "Texas City may be one of the most advanced refineries in the U.S.," says Antoine Halff, head of commodities research at the Energy Information Administration (EIA). "It's not a bad asset, it's a good asset."

Granted, the facility has had a checkered past. It blew up in 2005, and is currently facing a $10 billion lawsuit for a chemical incident there last spring. BP could use cash from the sale to deal with the impact of creating a $20 billion relief fund to clean up the Gulf of Mexico in the wake of the Macondo spill, which happened just over a year ago.

But Morningstar energy analyst Allen Good says major oil companies that actually have the wherewithal to run facilities like Texas City are also sellers, rather than buyers, in the refinery market. What gives?

Long-term, despite today's high fuel prices, the demand for gasoline in the United States and Europe is slowing, Good says, "People believe that the U.S. in particular hit peak gasoline demand in 2007 and will never really reach that again."

The EIA says that not only has gasoline demand in the United States decreased slightly this year compared to 2010, refining in general has been less profitable than other oil industry segments since at least the 1990s.

Demand slowed mainly because of the economic crisis, says Halff, and it won't pick up fast enough to match refining capacity in some regions. "There's excess refining capacity in the U.S.," Halff says. That may fluctuate short term, but, "in the longer term, we will see a decline because we are tightening standards, and cars will become more efficient." In other words, even though owning a refinery might be a good short-term bet, no company wants to risk getting stuck holding an under-performing asset as the market landscape changes.

While gasoline demand in certain markets will likely continue to decrease, Good says that U.S. consumers probably won't feel a lag in supply even if gasoline demand in Europe and the United States did suddenly pick up. Companies are now building refineries in China and the Middle East that are designed to export, and those operations will fill in gasoline demand here in the U.S., if necessary.

Of course, not every company is shedding its refining assets, but across the industry, oil majors are shifting refining operations out of U.S. and Europe and focusing on emerging markets.

Besides Texas City, BP is also selling a refinery in Carson, California. In March 2010, Chevron (CVX, Fortune 500) divested a facility in Pembroke, U.K. with a capacity of 210,000 barrels per day. Chevron has kept refineries with access to markets in Asia and Latin America, however, because gasoline demand is growing in those countries.

French energy giant Total sold a refinery in its home country last year and one in the U.K. this year, which should drop its refining capacity to 1.8 million barrels per day, down from 2.3 million barrels in 2006.

ConocoPhillips (COP, Fortune 500) is shedding refineries and other assets as part of a "shrink to grow" strategy that CEO James Mulva announced in 2009. The company has been lagging its peers in return on assets. To solve that problem, Conoco wants to reduce its total refining capacity to below 1.8 million barrels per day, down from its current 2.4 million barrels. Morningstar's Good says the strategy will likely work.

The companies that stand to profit from keeping large refineries are the ones that tie them back to their exploration and production businesses. Exxon (XOM, Fortune 500), for example, has identified real profits from refining certain substances it uses during exploration and production. Companies that don't integrate every part of their oil production chain might miss the opportunity to do that.

Shell (RDS) is similar to Exxon in placing a high value on the chemicals, other than gasoline, that come out of the refining process. While the company has reduced its total refining capacity by 1.6 million barrels per day since 2006, it has kept its larger refineries and focused on manufacturing chemicals used in natural gas production. Shell plans on increasing its natural gas assets to the point at which, in 2012, the company will produce more natural gas than oil.

But other companies with more separation between their producing and refining businesses may pull further out of refining, shift completely to emerging markets, or splinter completely like wildcatter Marathon (MRO, Fortune 500) did. Last January, Marathon announced plans to spin off its downstream operations. The market approved -- the company's stock went up following the announcement -- and Marathon's refining unit should benefit from solid profit margins in refining.

But even so, it won't be easy for the new company as long as their assets are U.S. based. Profit margins, thanks to the squeeze discussed above, won't be as high as they seem to drivers grumbling at the pump, Good says. Refineries use different benchmarks to measure the price of crude, and many refineries in the U.S. don't benefit from the best profit margins.

Thus, refineries in the U.S. and Europe -- BP's Texas City, for example -- are much less attractive to big oil bidders. So far, many of the buyers who have stepped in to bid for refineries up for sale have been private equity firms, Good says.

Foreign companies may be interested, the EIA's Halff suggests, but U.S. independents probably won't be. Many of them have investments tied up in natural gas, so adding a giant refinery wouldn't mesh with their portfolios.

That leaves plenty of refineries in the United States, mostly in areas outside of the Midwest and the Gulf, that simply don't make enough money to move the profit needle for their owners, and may never do so again. "A lot of them are going to have to be turned into terminals or shuttered," Good says, regardless of how high -- or low -- the price of gasoline goes. ![]()

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |