Search News

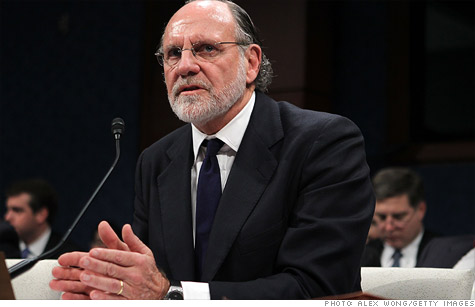

Jon Corzine, a former Democratic senator and governor from New Jersey, testifies on Capitol Hill last year.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- Nearly five months after some $1.6 billion in customer money went missing at bankrupt brokerage MF Global, the question remains: Will anyone be held responsible?

A congressional subcommittee will take up the issue on Wednesday in the latest hearing on Capitol Hill to focus on the firm's collapse. Watching anxiously will be the 38,000 former MF Global customers who are still missing money and are waiting for someone to be held accountable.

"We've been arguing for a long time that at a minimum, this was larceny," said John Roe, a partner at BTR Trading Group who has advocated on behalf of MF Global customers. "This was a company appropriating money that wasn't its own."

While the case had been quiet in recent months, that changed last week when the subcommittee released a memo detailing a critical $200 million transfer out of an account holding customer funds.

The memo has reignited questions about who at MF Global knew that customer money had been appropriated and how that information could influence a possible criminal case.

It cites an email from MF Global assistant treasurer Edith O'Brien saying the transfer, to resolve an overdraft of an account at JPMorgan (JPM, Fortune 500), came "Per JC's [Jon Corzine's] direct instructions."

The memo does not say, however, that Corzine ordered that the transfer use customer funds, in violation of industry rules.

Futures brokers like MF Global can hold their own cash in customer accounts along with that of their clients, and money belonging to the firm may be transferred out freely.

Testifying under oath before Congress last year, Corzine denied ordering the use of client money, saying he received assurances "both orally and in writing" that the transfer had been lawful.

Corzine's spokesman also said last week that the former New Jersey governor had not specified from which account the transfer was to be made

No one from MF Global has been formally accused of wrongdoing, though the FBI and federal regulators are investigating.

In a criminal case, prosecutors must prove there was a deliberate intent to appropriate customer funds, or failing that, that there was "willful blindness" by Corzine or others to the fact that such funds were at risk, said Michael E. Clark, an attorney with the law firm Duane Morris and a former federal prosecutor.

"The practical problem is that, if there were instructions given to move the money from customer accounts, can they establish a direct link or is this going to be more circumstantial?" Clark said. The testimony of lower-level employees, he added, could be crucial to building a case.

Finding charges that stick: Shortly after the transfer to JPMorgan, the banking giant requested that O'Brien sign a letter certifying that the transaction complied with industry rules on the protection of customer funds. O'Brien was "reluctant" to sign this letter, according to the memo from the subcommittee, and it was never returned.

In addition, Terry Duffy, the head of exchange operator CME Group (CME), has accused MF Global of falsifying accounting statements in the week prior to its bankruptcy to conceal its use of customer funds.

O'Brien has been summoned to appear at Wednesday's hearing along with several other former MF Global staffers, though she is expected to refuse to testify, invoking her Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

Leaving aside the issue of the missing money, there are other ways prosecutors might pin charges on MF Global executives.

MF Global was felled after its disclosure of billions of dollars worth of bets on risky European debt sparked a panic among investors. Trading partners called for increased margin payments and clients began taking their business elsewhere, leaving the firm scrambling for cash to make good on its obligations.

Less than two weeks before MF Global went bankrupt, however, executives assured staff from ratings agency Standard & Poor's that the firm was in good health. A week before the bankruptcy filing, CFO Henri Steenkamp told S&P that the firm was in "its strongest position ever as [a] public entity."

"Let's ignore the missing $1.6 billion for a second and let's talk about securities fraud, because you have the CFO running around telling ratings agencies that the company had never been in a stronger position, and that clearly wasn't the case," said Roe, the customer advocate.

Again, a fraud charge would require proof that misstatements by MF Global executives about the health of the firm were intentional. Lawyers for Steenkamp and Corzine did not respond to requests for comment.

There's also the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which requires corporate officers like those at MF Global to certify that the internal risk controls at their firms are adequate. Ironically, Corzine helped write this law while serving in the Senate.

Sarbanes-Oxley violations can carry prison terms of up to 20 years. While the law has seldom been used in this context over the years, Clark said it could be part of a broader case against MF Global executives.

"I would hate to be in their shoes," he said. ![]()