Search News

Netflix wants Congress to update the 1988 Video Privacy Protection Act. Lawmakers generally agree the law needs an update, but they're battling over how to do so.

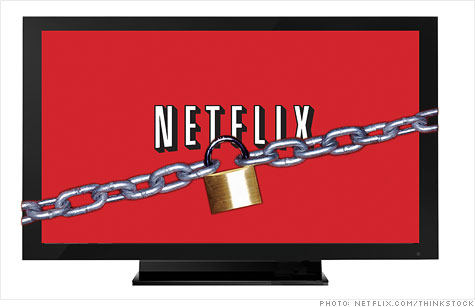

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- Several big-name brands have Facebook apps that instantly blast out users' activity -- the latest song they've listened to, or a story they just read. But in the U.S., there's one notable exception: Netflix.

The video streaming service is blocked from creating a Facebook app in America because of a 1980s law meant to protect consumers' privacy -- and lawmakers are tussling over how to update it.

It's called the Video Privacy Protection Act (VPPA), and it highlights the issue of old legislation lagging new technology. Netflix (NFLX) is lobbying Congress to change what it called an "ambiguous" and "confusing" law in a September blog post.

VPPA arose from strange circumstances surrounding the failed Supreme Court nomination of Robert Bork. While Bork's nomination hearings were taking place in 1987, a freelance writer for the Washington City Paper talked a video store clerk into giving him Bork's rental history.

The writer, Michael Dolan, later wrote that he was proving a point: "Bork said, Americans enjoy only those privacy protections conferred by legislation." Bork's rentals were unremarkable, but the City Paper published the list anyway -- much to the chagrin of lawmakers.

Congress quickly passed VPPA a few months later. The law prohibits "a video tape service provider" from disclosing its customers' "personally identifiable information," unless the customer provides written consent.

It's clear that Congress tried, in 1988, to legislate for a post-VHS world, referring to "prerecorded video cassette tapes or similar audio visual materials." But Netflix said the vague language leaves the present-day situation unclear.

"It's ambiguous about whether it applies to us. We just don't know, and we'd rather be in compliance than risk stepping over the line," Netflix spokesman Steve Swasey told CNNMoney.

Meanwhile, Netflix's Facebook app is up and running in all of the other 46 countries where it offers service -- all except America.

The Hulu question: Further muddying the picture: Netflix competitor Hulu launched its own Facebook app late last year. Users can opt-in to share their viewing history -- or opt out.

Hulu declined to comment for this story, and it's unclear why its app doesn't flout VPPA. One lawyer says it's a swampy gray area: It could come down to the fact that Netflix offers discs in addition to streaming video, while Hulu is streaming-only.

"Arguably, the intent of the law is that the form of the video -- streaming or disc -- shouldn't matter," says James Gatto, head of social media, entertainment and technology at the firm Pillsbury Law. "An attorney general would say that. But Hulu could possibly argue that the law covers only physical goods."

The issue, Gatto says, is that "to a certain extent, legislators don't really want to legislate technology. They want to craft an objective. But in this case, the potential ambiguity is a problem."

Legal battle: Clarity could come in the form of an updated VPPA, which Netflix is lobbying for -- but legislators have been fighting for months over the best way to amend the law.

Rep. Bob Goodlatte, R-Va., introduced an amendment last year that would change VPPA in two ways: customers can provide consent "through the Internet, and in advance for a set period or until such consent is withdrawn." That amendment, called H.R. 2471, would clear the path for Netflix.

The House of Representatives passed the bill in December, by a vote of 303-116. But the method of consent has met resistance with Senate Democrats.

"A one-time check off that has the effect of an all-time surrender of privacy does not seem to me the best course for consumers," Sen. Patrick Leahy, D.-Vt., said at a hearing about the amendment in January.

Sen. Al Franken, a Minnesota Democrat who chairs the Senate subcommittee on privacy, technology and the law, also said he opposes the one-time consent method.

"After hearing the testimony today, I do think that it is time to update [VPPA]," Franken said at the hearing in January. "But I'm still unconvinced that H.R. 2471 is the way to do that."

Goodlatte told CNNMoney he's frustrated that movies are regulated differently than other media.

"This is how people do it now for books and articles, and they don't need the government's approval," Goodlatte said. "The only reason there's a distinction is because the government took control of the issue in 1988."

That's the philosophy Netflix subscribes to, according to spokesman Swasey: "We're living online. We're living in public. The fact that this is not regulated for music, books and other media, but it is for movies...it's just unfair to consumers."

But one lawyer says that if lawmakers are going to amend the bill, they should focus on the bigger picture.

"They need to clarify which formats the law applies to -- discs only, or all formats," says David Gurwin, an entertainment and media lawyer at the firm Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney. "Don't leave it up to courts to decide."

Of course, even with modern amendments, it's impossible to guarantee that a law will apply to as-yet-unknown tech advancements.

"By the time the legislation is passed, the technology may be obsolete," Gurwin says. "New technology is always going to outpace the law's ability to catch up."

In the meantime, VPPA is giving Netflix trouble in more than one way. Just last month, the company disclosed that it paid $9 million to settle a lawsuit brought in 2011, by customers who alleged that Netflix didn't delete their personal account data after one year -- another provision of VPPA.

There's no set timeline for future hearings and potential votes on an update to VPPA, but Netflix' Swasey says the company is "hopeful that we can get it addressed in this Congress, this year." ![]()