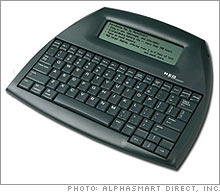

The trouble with gee-whiz gadgetsToo many gizmos these days are loaded with features we don't need - or use. Business 2.0's Chris Taylor explains why that's all about to change.(Business 2.0 Magazine) -- I'm writing this column using the hottest gadget to have entered my house this year. It's not a flashy PDA cameraphone with a Bluetooth headset or a WiFi-enabled MP3 player with streaming video capability. In fact, this isn't a new product at all. It's a three year-old word processor called the Neo--and everything about it points to the future of electronic devices.

The Neo, by a tiny company called Alphasmart, was initially designed to be used by students and their educators. But in true Web 2.0 style, the users spoke louder than the designers. Over the last three years, Neo has been embraced less by students than by an unexpectedly different audience: journalists and writers, who have written little hymns to the Neo in magazines, blogs, and even a Flickr group where they share pictures of their Neos. Why? Because it's supremely easy to use. It is the ultimate writing tool for an ADD age, as countless reviews on popular sites like Boing Boing have pointed out. You can't do anything other than write on it, in one of eight enormous files. It's the size of a sheet of paper, light as a shoe, and the battery lasts for 700 hours (no kidding) on a single charge. No need to plug it in or sit through a long, noisy startup sequence - the thing is instantly and quietly turned on like a lightbulb. When your masterpiece is written, simply hook it up to a computer or a printer with a USB cable, and hit "send" to transfer into a text file or print it out. As one Wired blogger instructed when reviewing it: "Throw away the computer and write." I myself gave the Neo an enthusiastic thumbs up in the pages of Time magazine when it first came out. I discovered it was not only a great transcription tool for interviews and meetings, it was also the only device better than pen and paper for writing long chunks of fiction in a coffee shop. No email, no Minesweeper, no web-browsing temptations, no low battery warnings. It was the first essential device to have entered my life since the iPod became one of my sacred pocket items back in 2001. When I lost my Neo in the chaos of a recent house move, I found I couldn't live without it and had to scour eBay (Charts) for a cheap replacement (AlphaSmart, knowing it's on to a good thing, has kept the price at a robust $250). Like the Apple (Charts) iPod, the Neo does one thing very well. Of course, iPods now have a lot of functionality: they can display video, photos, and play games. But that doesn't mean consumers are using all these functions. Next time you're on a street or a bus in a busy city, count how many people are listening to iPods that are stashed away in pockets, identifiable only by their white earbuds. They just want to throw the computer away and be served audio treats. That's why the iPod succeeded where its predecessor products bombed. Few people remember that the iPod was actually regarded as a Johnny-Come-Lately MP3 player with a too-small 5-gigabyte hard drive when it first came out - "we're pretty late to the party," CEO Steve Jobs admitted to me at the time. But it was super easy, which larger competitors like the 20-gigabyte Rio Nomad weren't. My parents figured out how to use the iPod within five minutes. They didn't even want to pick up my Nomad. Nor, I instantly decided, did I. The iPod and the Neo are in the vanguard of a new wave of simple tech. There are two forces driving this wave. The first is the graying of the baby boom generation. Society is about to take a distinct turn for the senior, and that means device manufacturers are already starting to think simple: large keypads, bright screens, and stripped down functions. This is the world of the $150 HP Mailbox, a printer made by Hewlett-Packard (Charts) that does nothing but print out messages from a specially spam-protected e-mail account in large, friendly letters. It's a world where we're jabbing our arthritic fingers at the giant buttons on the $147 Jitterbug Dial phone from a company called GreatCall. GreatCall also makes a "OneTouch" special security phone, which has no numbers and just three dial buttons: Operator, Tow and 911. Fewer buttons means happier new customers. Just ask Palm Inc, whose basic PDA now contains a third of the number of buttons on the classic Palm V. Increasingly, less is more. And not just for seniors (or for the 11-and-under market, who are also getting simple little cell phones of their own, such as the five-button Firefly). All else being equal, most of us prefer our technology to have a simple, well-made, intuitive feel. That's why the Wii console has been a bigger hit for Nintendo than the PlayStation 3 has for Sony (Charts). Controlling a game by moving your hands around in the air, as the Wii allows, makes a lot more sense for beginners than mashing away at a dozen confusing buttons on a PS3 controller. The second trend helping the simple tech movement is the increasing ubiquity and miniaturization of processing power. You're already surrounded by computer chips that do one thing very well--in your car, in your microwave, in your DVD. Later this year we'll see the launch of the highly-anticipated Chumby, an alarm-clock computer that has a handful of handy Web-browsing functions that you interact with by squeezing or throwing around the room. It's not too much of a stretch to think of computers embedded in our clothes. One button on your button-down shirt collar might be used for recording voice memos to yourself, the other for calling your spouse. (Just don't get the two mixed up.) Function always finds its perfect form given the technology to do so, as any industrial designer will tell you. When computers are cheaper than CDs, smaller than tic-tacs, and bought by the dozen in convenience stores, there'll be no need to make any of them do more than one thing. Our era will be looked back on as a strange technological blip of overburdened devices - the ADD age. _____________________________ More from Business 2.0 Magazine: The Next Net 25: Startups to watch in 2007 Google and the beauty of failure Best Buy rethinks the time clock In defense of bosses from hell |

Sponsors

|