America sours on free trade

Economic anxiety has inspired a backlash against free trade, as a new Fortune poll shows, giving Democratic candidates a potent issue. Will it lead to protectionism?

(Fortune Magazine) -- "We are the champions - of the world" may be the verse that rings out in stadiums across the U.S., but in the great game of global trade, Americans are increasingly feeling like the losers. A large majority - 68% - of those surveyed in a new Fortune poll says America's trading partners are benefiting the most from free trade, not the U.S. That sense of victimhood is changing America's attitude about doing business with the world.

We are a nation crawling into a fetal position, cramped by fear that America has lost control of its destiny in a fiercely competitive global economy. The fear is mostly about jobs lost overseas and wages capped by foreign competition.

But it is also fueled by lead-painted toys from China and border-hopping workers from Mexico, by the housing and credit crisis at home, and by the residue of vulnerability left by 9/11 and the wars that followed. Americans were willing to experiment with open borders during the exuberant 1990s. Today that mood has darkened. We are turning inward. Especially now, as the U.S. economy sputters, we are on the verge of becoming a country of economic nationalists.

That may be hard to imagine if you are reading these words from the aisle seat of a packed business-class cabin on one of those new nonstop flights to Guangzhou or Mumbai or Abu Dhabi, the numbers on your company's latest deal flashing on your laptop screen. It may be hard to imagine, too, if your factory can't keep up with orders for diesel engines flooding in from Beijing or electronic parts requests from Brazil. Despite a continued massive trade imbalance, U.S. exports grew 12% last year, providing a cushion against the painful housing downturn.

Yet for several years average Americans have increasingly felt that they're running in place. Median household income in 2006, at $48,201, was barely ahead of where it was eight years earlier. So the prospect of a recession has made the anxious middle class even more so. Coming in a presidential election season, the approaching storm clouds have turned the economy into the No. 1 issue on the campaign trail. Fear is a potent force in American politics, and Democratic Party leaders have astutely tapped into rising voter unease about globalization.

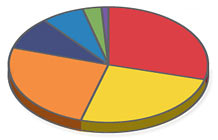

Fortune's poll, a survey of 1,000 adult Americans taken Jan. 14-16, shows that voters have identified winners and losers in the free-trade agenda. Nearly half of those polled believe that growth in international trade has made things better for consumers (though nearly as many think it has made things worse), but 55% believe American business has been harmed, and 78% think it has made things worse for American workers. (See the complete poll results)

Candidate Barack Obama encapsulated this feeling on the campaign trail in December when he said, "People don't want a cheaper T-shirt if they're losing a job in the process." What might be dismissed as just campaign-season populism has been given intellectual credibility by some economists, notably Princeton's Alan Blinder, a professed free-trader who has crossed over into the camp of those concerned about the outsourcing of service industry work. He has predicted that as many as 40 million U.S. jobs could be vulnerable, thanks to modern technology and more than one billion eligible new workers.

Speaking in November at a Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago conference, he declared, "It's not the British that are coming. It's the electrons that are coming, and it's going to cost jobs." The national mood swing is a dramatic one. With stubborn optimism and entrepreneurial swagger, Americans led the world in building a roadmap for global commerce during the 1990s, when Bill Clinton overcame resistance from organized labor to sign the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), linking the U.S., Canada, and Mexico to create the world's largest trade bloc.

It was an internal party battle that Clinton took on with gusto, beginning in the fall of 1991, when as a presidential candidate he shut down a debate among his strategists over what position he should take on trade. "Finally, Clinton looked up over his spectacles and said, 'I want all of you to understand something: I'm not going to run as an isolationist, and I'm not going to run as a protectionist,'" recalls William Galston, a party strategist now at the Brookings Institution. "I'll never forget that day."

President Clinton was able to bring along a majority of the public on an aggressive free-trade agenda. But today, according to the Fortune poll, nearly two-thirds of Americans are even willing to pay higher prices to keep down foreign competition. Now Clinton's party is leading America into this new era of doubt, its economic gurus convinced that globalization - in its current form - is costing the middle class and enriching an elite.

Both Democratic frontrunners want changes to NAFTA, which Hillary Clinton now says has "serious shortcomings." Candidate Clinton also says she will take a "hard look" at the U.S. position in the Doha round of World Trade Organization talks, insisting "there is nothing protectionist about this." Obama praises globalization for bringing millions of workers into the global economy but wants a tax code that discourages companies from shipping jobs overseas.

No matter which candidate or which party takes control of the White House one year from now, free trade will - in the words of Hillary Clinton - take a "time-out." That's because Congress - which will most likely remain in the hands of the Democrats regardless of who wins the White House in November - took away President Bush's ability to negotiate trade deals by quietly letting so-called fast-track authority lapse last summer. And lawmakers won't hand that power back to any new President - Democrat or Republican - without major new federal programs (and new trade rules) designed to ease the stress of globalization on U.S. workers.

The Democratic mantra is now "fair trade, not free trade." During a "time-out" on trade deals, a President Obama or President Clinton would seek to extend international labor and environmental standards (already approved by Bush in the current crop of deals) and step up enforcement against China and other trading partners. A Republican President will need to accede to most of those demands to move a trade agenda forward in a Democrat-controlled Congress, and at least one of the party's leading presidential candidates - former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee - is mostly in sync with the Democratic mood, complaining about "an unlevel, unfair trading arena that has to be fixed."

It's not just America that's experiencing a trade backlash. Peter Mandelson, the European Union's commissioner for trade, looks past his frustrating meetings with free-trade skeptics on Capitol Hill to his own continent and describes growing "economic insecurity that is ripe for disaster, that feeds populism and protectionism." Former U.S. Trade Representative Mickey Kantor told Fortune that as the global economy becomes more integrated, "trade has lost more and more credibility all around the world - India, Brazil, France. For some reason, everyone thinks they are the loser."

In the U.S. the newly shuttered Maytag plant in Newton, Iowa, doubles as an altar to the political spirit of economic nationalism. In the months leading up to the Iowa caucuses, Democratic candidates -and Republican Huckabee - trooped into town to genuflect and borrow its brick image for their argument that globalization has hurt the middle class and enriched a narrow elite on Wall Street. Maytag, which anchored this town for more than a century before it was battered by foreign competition, seemed the perfect election-year symbol for the price of globalization.

But was U.S. trade policy really the culprit? "Maytag was mismanaged," says town mayor Charles Allen. By the time rival Whirlpool gobbled it up in 2006, Maytag's market share was at an all-time low, customers were grumbling about the quality of its washers and dryers, and one analyst was quoted describing the company as a "two-inch putt from bankruptcy." Maytag CEO Ralph Hake was blamed for cost cutting that destroyed innovation.

When I visited Newton on the eve of the Iowa caucuses, I expected a dying town. Instead I found a vibrant community of 16,000 with serene neighborhoods and a bustling downtown. The damage caused by the plant's closure shouldn't be minimized - unemployment in the area shot up to 5.6%, far above the state average. But Allen says the town had long been adjusting to the prospect of losing its largest employer. A NASCAR raceway has opened; a new biodiesel plant is up and running; TPI Composites, a wind turbine manufacturer with plants in Mexico and China, has just agreed to build a new facility with 500 jobs. And about 50 former Maytag engineers have launched their own research and development business, called Springboard.

All this local ingenuity and determination to create a new economy was lost in the political noise leading up to the Iowa caucuses. Most analysts agree that the underlying reason for public anxiety over globalization is the visibility of factory closings and the stagnation of income. But the reasons behind this decline are complex. Technology, for one. "It's first and foremost a story of technology and of the technology driving out middle-income jobs - whether they are in services or in manufacturing," economist Laura D'Andrea Tyson, an advisor to Hillary Clinton, told Fortune's Global Forum last October. By contrast, for educated elites "technology gives you a global stage on which to earn your income."

Diana Farrell, director of the McKinsey Global Institute, cites demographics for a "very large part of the softening in growth of wages." In other words, wages moved upward with a baby-boom generation that saw rising waves of Americans going to college and then on to higher-paying jobs. But that upward motion has crested; the population has stabilized. But those aren't answers that satisfy voters in a heated election campaign. (As Tyson noted, "On the campaign trail, a one-sentence answer is what matters.")

So Democratic leaders have tapped into the sour public mood over globalization. "The public is not listening for how you expand trade," says Kantor, a Democratic veteran now informally advising Hillary Clinton. "The public wants to hear just how frightened you are. Someone has to say, 'I understand it, I get it.'" But then what?

Most Democratic leaders insist they don't want to, nor believe they can, halt the global flow of commerce. Where they hope to connect with voters is by promising to strengthen the safety net. "America frankly does a disgraceful job with displaced workers," declares economist Blinder. Americans resoundingly agree: In our poll, 79% of those surveyed said the U.S. government hasn't done enough to help workers who lose their jobs to foreign competition.

People in the survey favor more job training, longer unemployment benefits, and limits on imports from countries that use child labor or pollute the environment. Blinder calls for an education system more focused on jobs that can't be shipped offshore. There are plenty of worthy ideas, but policy prescriptions have to be combined with leadership that encourages Americans once again to believe in their ability to compete in the world. Just as the shutdown Maytag factory provided an easy symbol of globalization's cost in the 2008 election, the town of Newton, Iowa, could symbolize the ultimate gains of adjustment in the next. But only because of a belief by local leaders that they wanted to be part of a global economy, not shut off from it. ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More