Debt markets remain on edge

While panic subsides, money remains tight as wary investors brace for the next hit.

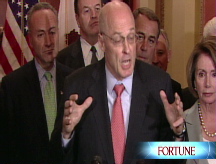

NEW YORK (Fortune) -- For all of Henry Paulson's talk about restoring confidence, fear remains the prevailing emotion in the bond market.

Treasury Secretary Paulson and Federal Reserve chief Ben Bernanke appeared on Capitol Hill Tuesday to ask Congress for $700 billion in petty cash.

Spending that money in the markets for mortgage-related assets, Paulson said Tuesday, will help the nation "avoid a continuing series of financial institution failures and frozen credit markets that threaten American families' financial well-being, the viability of businesses both small and large, and the very health of our economy."

But so far, there's been little sign of a thaw in the credit markets. True, the rates for short-term Treasury securities have risen from the panic levels seen last week - the three-month Treasury bill yielded 0.83% Tuesday, off a low of 0.03% last Wednesday following the near collapse of insurer AIG.

The spreads between Treasurys and privately issued securities, though, remain elevated, a signal that investors remain nervous about assuming risk.

That fear has hampered Paulson's efforts to unfreeze the housing market. Mortgage rates, after falling sharply earlier this month in the wake of Paulson's plan to temporarily nationalize mortgage financiers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, have jumped in the past week. A 30-year fixed-rate mortgage was recently quoted by Bankrate.com at 5.97%, up from 5.72% last week.

And despite federal promises to ease the logjam in the financial sector, investors continue to flee from the bonds of financial companies.

"People don't even want to be associated with these guys," says William Larkin, a fixed-income portfolio manager at investment adviser Cabot Money Management in Salem, Mass. "There has just been a lot of heavy selling everywhere."

One measure of financial stress can be found in the so-called TED spread, the difference between the interest rates on the three-month Treasury bill and the three-month overnight bank lending rate as measured by Libor, the London Interbank Offered Rate. The TED spread shows the degree to which banks are willing to lend to one another.

The spread narrowed some this week, to around 240 basis points - or 2.4 percentage points - from 288 basis points at its recent wide point last Wednesday. But before the credit crunch erupted in August 2007, the TED spread typically ranged between 20 and 30 basis points.

That tenfold expansion shows that capital-constrained banks remain unwilling to make loans during a period in which the health of just about every major finance company has been questioned. Treasury, after all, unveiled its latest plans only after the meltdown of the financial sector threatened the independence of the two remaining independent Wall Street firms, Morgan Stanley (MS, Fortune 500) and Goldman Sachs (GS, Fortune 500). The brokerage firms have since received approval to reorient themselves as commercial banks, in a move with uncertain implications for the rest of the industry and taxpayers.

If overnight lending is perilous, so is investing in anything longer-term. Larkin, referring to the duration of bonds he's looking at, says he is "staying away from anything that's not short," amid questions about the economy's health and the shape the financial sector will take when the crisis mentality lifts.

Larkin says the wide spreads on even high-grade corporate debt look alluring at first glance, by promising investors a high yield they can't get buying government bonds. But after the past two weeks, which saw the government take over Fannie (FNM, Fortune 500), Freddie (FRE, Fortune 500) and AIG (AIG, Fortune 500) while letting Lehman Brothers fail, Larkin says the pull of higher yields isn't sufficient to draw him into the market for any bond that matures in more than a year or two.

"This is either a phenomenal buying opportunity or a huge trap," he says. "At some point you have to wonder why the market has been pricing things this way."

Larkin and others say the uncertainty in the marketplace is attributable in part to Paulson's failure to present a convincingly transparent rescue package.

While the plan to buy $700 billion worth of mortgage securities could help banks, Larkin says, it leaves open the question of what happens to homeowners struggling to keep their houses - not to mention issues tied to how the securities to be acquired by the government are priced, and how that affects bank balance sheets.

"Markets and global observers seek clarity, comprehension, and clearly articulated processes," writes David Kotok, chief investment officer at investment adviser Cumberland Advisors in Vineland, N.J. "They have been receiving the opposite. This has created a huge global uncertainty, which has caused risk premia to reach all-time expansive levels."

While spreads may come in as the federal plan comes into fuller view, Larkin expects that we're going to be dealing with extremely volatile markets for some time. That could punish stock investors and make it more expensive for companies to borrow money.

But Merrill Lynch economist David Rosenberg says the nervous corporate market could spell opportunity for investors in government debt - and perhaps ease fears that the dollar will sink under the weight of massive Treasury bond issuance.

"While it is true that the government intends to boost its debt load by $700 billion in the next two years," he writes Tuesday, "if the demand for Treasuries from households, mutual funds, pension funds and the commercial banks ends up matching what occurred in the early 1990s, this potential buying power could well exceed $2 trillion and totally overwhelm the incremental net new issue activity." ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More