Lime Wire seeks legitimacy

The music file-sharing company is trying to shed its pirate image. It just might work, too.

NEW YORK (Fortune) -- Recently, Nat Hays, chairman of Brooklyn's independent +1 Records, wanted to break a record by one of his label's new bands, The Morning Benders. So he went straight to Apple's iTunes Music Store.

That was no surprise. iTunes is the biggest retailer of digital music. But Hays also enlisted a less expected partner: Lime Wire, the music file-sharing service detested by so many of his major label colleagues.

"I consider Lime Wire a really important player in what we are trying to do," said Hays.

The major labels couldn't disagree more. The Recording Industry Association of America, their trade group, blames much of the music industry's declining sales - a 12% drop in 2007 alone - on illegal file-sharing made possible by such technology. The RIAA is doing its best to put Lime Wire, the last surviving big peer-to-peer provider with 70 million monthy users, out of business.

"Lime Wire is number one with a bullet," said Eric Garland, CEO of Big Champagne, a digital entertainment analytics company. "It's the Napster of today."

At the same time, however, Lime Wire is trying to reinvent itself as a legitimate music service with much to offer to its foes. It is supporting independents like +1 and even courting the big four record companies - Universal, Warner Music, EMI and SonyBMG - with an offer to transform its network of users into a Google-like music search engine what would be extremely lucrative for them.

"We'd love to work with the entire music industry," said Lime Wire CEO George Searle. "I think there are some people in the majors who see the potential of Lime Wire."

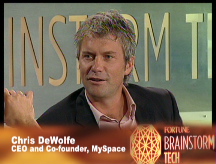

Not long ago, the thought of the big labels going into business with Lime Wire would have been laughable. But the music industry is changing rapidly. Earlier this year, Universal was suing MySpace in federal court for copyright violations. Now the majors are joint venture partners in the social network's new ad-supported free music service.

In the end, some would say, the future of of Lime Wire and the big record labels, too, may boil down to this: Does the music industry want to embrace the future (or even the present) and work with its one-time adversaries like Lime Wire? Or would it rather go down fighting its last and most epic battle over copyright infringement in the digital age?

+1 Records' Hays has made his choice. His label made a live EP by The Morning Benders for Lime Wire's new music download store. Lime Wire returned the favor by creating fliers for the EP. The band is passing them out to fans on tour.

"They are are thinking outside of the box and investing in the band," said Hays, referring to Lime Wire. "Those are the kind of people we want to work with."

The Lime Wire Store has only been open since March, but it offers almost two million independent label songs for 99 cents from bands like Death Cab for Cutie and The Hold Steady. The company added music by these two popular bands and many more through a deal announced in August with The Orchard (ORCD), a big online music distributor.

"The Orchard didn't take this step lightly - we were in talks with them for 18 months," said Orchard CEO Greg Scholl. "In the end, we are pragmatists and recognize that 70 million users have downloaded their software."

Lime Wire's search engine plan is even more ambitious. Lime Wire's Searle says the company would like to compensate record labels and their artists when users request their songs. The technology company has hired prominent music industry attorney Michael Guido, whose clients include Jay-Z, Avril Lavigne and OutKast, to sell the plan to the majors.

"This is something that should have happened a while ago," he said. "People now lament the opportunity they would have had if they'd licensed music to Napster. This opportunity is a million times bigger than Napster."

Lime Wire seems to be trying to rebrand the company, though its executives disagree with that characterization. Later this month, Lime Wire will announce plans to let users create their own private social networks within its peer-to-peer universe.

That will be attractive to major label executives, many of whom talk about the growing importance of social networks like MySpace and Facebook to the future of the business. "We've always been a social sharing network, but we never have described it like that," said Lime Wire COO Kevin Bradshaw.

First, Lime Wire has to resolve its differences with the RIAA. In 2006, the music industry trade group sued Lime Wire in a bid to put it out of business just as it did with Napster, Aimster, Grozkster and KaZaa.

The RIAA complains that Lime Wire has built its enormous user base and created a lucrative business for itself by enticing its customers to download copyrighted music for free. Lime Wire makes almost all of its money by getting its users to upgrade from its free software to its $34.95 Lime Wire Pro.

In July, the RIAA argued in a legal brief that, after two years of litigation, "the undisputed facts confirm what everybody (certainly every teenager and college student) already knows: Lime Wire's eponymous peer to peer software... is good for one thing and used for one thing - massive infringement of sound recordings each and every day."

The association estimates that 99% of the download requests by Lime Wire users are for copyrighted songs.

Lime Wire responds that it shouldn't be held responsible for the behavior of its users. The company's executives say they have never encouraged or condoned illegal-file sharing.

This is central to Lime Wire's defense. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2005 that Grokster, a similar peer-to-peer service, was liable for the violations of its users because it had induced their activities.

The RIAA, however, cites many examples of alleged inducements by Lime Wire to turn into "the next Napster."

Given its legal troubles, Lime Wire's campaign to legitimize itself may ultimately be its wisest litigation strategy. Guido calls Lime Wire "the last best opportunity for the music industry to save itself."

That may be overstating the case. But the major labels can't ignore that he's saying - even if the RIAA is right about Lime Wire.

"The people who are going to want to steal are going to steal," said Lio Ceraza, co-owner of Kanine Records, another Brooklyn independent that licenses songs to Lime Wire. "You can't stop them. You have to give the others the avenue to buy stuff." ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More