WiMax: Not dead yet

It's been a rough road for the wireless technology that promises faster Internet speeds. But don't write it off just yet.

NEW YORK (Fortune) -- For the last couple years, depending on who you asked, WiMax was either bound for spectacular success or it was dead on arrival.

Well, the wireless technology that promises faster Internet speeds has finally arrived. The city of Baltimore now has WiMax coverage and Portland, Ore. will get it in early January. More cities are expected to follow.

After some sturm and drang, the stars are finally aligning for Clearwire (CLWRD), the wireless broadband provider that is leading the WiMax charge. Earlier this month, Clearwire completed its merger with Sprint's WiMax unit. And the Kirkland, Wa.-based company, founded by telecom pioneer Craig McCaw, has secured $3.2 billion in funding from Google (GOOG, Fortune 500), Intel (INTC, Fortune 500) and Comcast (CMCSA, Fortune 500), among others.

The stakes are high. Mobile technology is marching toward the point where faster Internet connections are ubiquitous, so we're not just making phone calls from anywhere to anywhere but pumping huge amounts of data too. Infonetics Research estimates the WiMax market will grow to $7.7 billion in 2011.

But the companies behind WiMax aren't the only ones who want to build a vast wireless network. WiMax naysayers point to a rival technology called LTE, or Long Term Evolution, as WiMax's biggest threat. Like WiMax, LTE is known as fourth-generation, or 4G, which is just the cellphone industry's way of describing the next stage of faster speeds on mobile devices. (The current cellular network we use to make calls is 3G, or third-generation.)

Verizon (VZ, Fortune 500) and AT&T (T, Fortune 500) have declared their allegiance to LTE, with Verizon saying it will have the technology deployed somewhere in the United States by this time next year. But LTE is still behind WiMax in development, and given the time it also takes for device-makers to line their products behind a new technology, mass adoption is at least a couple years away.

Clearwire, meanwhile, says it has lined up more than 80 vendors that are supporting WiMAX, including Samsung, Nokia, and Motorola.

But like any new standard, WiMax must confront the old chicken-and-egg problem: enough device makers have to design products for WiMAX for the technology to take off, but those vendors have to be convinced first that the WiMAX network will be widely available.

"If you have huge swaths of the world covered in 3G standard," said Jeff Belk, a former senior vice president of strategy and market development at Qualcomm, "and you have tiny little islands starting in WiMax, it's silly strategically to commit to the tiny little islands when you have hundreds of millions of devices you want to sell."

In the end the two technologies might just coexist. Clearwire CEO Ben Wolff has suggested as much, saying: "This isn't the technology war that some have made it out to be."

When Wi-Fi first appeared, there was plenty of handwringing over whether the market could sustain both Wi-Fi and 3G. "When people said Wi-Fi was going to crush 3G [third-generation wireless broadband], I wrote a paper saying they're going to be complementary over time," said Belk.

Belk was right. Today cellphone users can access the Internet not just with Wi-Fi but also 3G networks. The iPhone, for instance, can communicate wirelessly using four different technologies: two versions of 3G, Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, which enables short-range connections.

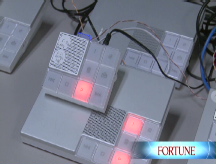

Clearwire argues that WiMAX promises an unusually broad platform, since the technology is designed for going online and delivering data. "Anything an Internet application can do, we can do too," said Scott Richardson, chief strategy officer for Clearwire.

That means WiMax-enabled devices could one day be used for mobile calls over the Internet, mobile broadband, home broadband, or even video conferencing, all on one network. This is in part why you see a company like Comcast backing WiMax. It's a way to keep selling broadband to customers, even after they've left their homes.

LTE's backers hope someday to funnel that much data as well, but for now WiMax has a crucial headstart.

WiMax's biggest rival is the current 3G cellular network. Verizon, for instance, makes it easy for customers to make the most of its 3G network, called EV-DO: if you're taking a train from New York to DC and want to access the Internet from your laptop, you need a $60 monthly data plan plus a 3G plug-in card that Verizon sometimes offers free with a rebate. The connection speeds are slower than WiMax and what you get at home through a wired broadband connection, but your laptop will work in most populated parts of the country.

On a recent trip from New York to Baltimore, the WiMax service then operated by Sprint (and now folded into Clearwire) worked flawlessly. But out of Baltimore city limits, it was back to 3G.

When asked about this, Clearwire's Richardson says upcoming devices that support both 3G and WiMax will give people flexibility to move around there's a wider WiMax network. On Wednesday Sprint unveiled its first dual-mode modem.

Can WiMax go nationwide and convince device-makers to go along? Clearwire will need much more than $3.2 billion from its supporters to build nationwide infrastructure, and this is a tough time to raise money. But Julie Ask, an analyst with Forrester, points to WiMax's powerful backers. "I wouldn't underestimate what they're willing to do to make this work," she said. ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More