A banker of the old school

After Barack Obama won Peter Fitzgerald's senate seat, the former politician took $4 million of his own money and opened a bank. His approach to finance is a far cry from the practices that have brought the big boys to their knees.

|

| Peter Fitzgerald photographed in the Chain Bridge bank in McLean, Va. |

|

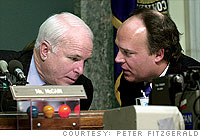

| Peter Fitzgerald served as a Republican in the Senate alongside John McCain before turning over his seat in 2004 to Barack Obama. |

|

| His father, Gerald Fitzgerald, was chairman of Chicago's Suburban Bancorp. |

|

| Peter, the little guy on the bench, sits with his siblings in 1968. His extended family has been involved with 57 community banks since the 1940s. |

(Fortune Magazine) -- When Peter Fitzgerald was in the U.S. Senate, he refused to vote on any bill that was banking-related. He wouldn't even take part in the debate.

It's not that he wasn't well versed in the subject of finance. In fact, Fitzgerald was practically born into banking - his extended family has managed or founded some 57 community banks since the 1940s. And before running for the Senate as a Republican in 1998 (he defeated Democratic incumbent Carol Moseley Braun), Fitzgerald had been everything from a teller in his college days to a bank attorney and bank general counsel in the 1990s.

Fitzgerald's family was so immersed in the banking world - his three brothers own seven small banks among them - that he felt he had to recuse himself from all banking matters that came before the Senate. (Fitzgerald himself has a net worth of at least $79 million and bank stock holdings in excess of $25 million, according to his last Senate financial-disclosure form.)

"I even recused myself from Alan Greenspan's reconfirmation vote as Federal Reserve chairman," Fitzgerald says. "Greenspan wanted to know why I was the only one who wouldn't vote for him."

In hindsight, it's a shame that Fitzgerald stayed on the sidelines as the nation's banks engaged in high-risk behavior. He claims that if he had immersed himself in banking matters, his political enemies would have accused him of pursuing policies that benefited his family.

But after Fitzgerald left the Senate in 2004, he set out to launch a bank that would be a showcase for the fiscally conservative principles he had learned as a boy. In August 2007, with the mortgage meltdown already underway, he and a handful of investors launched Chain Bridge Bank, a single-branch operation in the tony Washington suburb of McLean, Va. Fitzgerald put $4 million of his own money - as well as another $4.5 million of his family's - into the bank, whose startup costs were $18.5 million.

One of Chain Bridge's hallmarks is Fitzgerald's refusal to allocate more than 55% of his deposits to loans. (The U.S. average is 97%, according to FDIC data.) Because of the credit crisis, many banks, including a few of the majors, are coming around to Fitzgerald's way of thinking about liquidity. Peruse the first-quarter earnings releases that have gone out in the past couple of weeks, and you'll see that banks are now touting declines in their loan-to-deposit ratios.

Fitzgerald's contrarian approach to banking is in step with his politics. He was the only senator to vote against the post-9/11 airline bailout, and he's best known for nominating Patrick Fitzgerald as U.S. attorney for Chicago. Patrick Fitzgerald (no relation) would later become the bane of his fellow Republicans.

Launching a bank in this economy may sound insane, but star bank analyst Meredith Whitney has been saying since last year that the timing couldn't be better. First, a new bank starts out with a nontoxic balance sheet. Second, its earnings are juiced by a steep yield curve that allows for a healthy spread between the interest the new bank is paying depositors and the rate it's earning on its loans. And best of all, it is competing with established banks that don't want to lend - they're focused more on plugging leaks in their balance sheets than on making new loans.

Some banks are so desperate to pare loans from their books that they're stiff-arming their best customers in hopes that they'll refinance with another bank, thereby removing loans from their balance sheets. That's essentially what happened to Michael Oxley, a former U.S. representative from Ohio, when he tried to refinance the mortgage on his vacation home last year. "They weren't the least bit interested in new real estate lending," Oxley says of his old bank. "Chain Bridge was all over it."

***

Gerald Fitzgerald, Peter's father, always emphasized to Peter and his brothers that it wasn't safe for a bank to allocate more than half its deposits to loans. Gerald was chairman of Chicago's Suburban Bancorp - where Peter was general counsel - before Gerald sold Suburban to Bank of Montreal in 1994 for $246 million.

"The reason is that loans are illiquid," says Peter. "If you go into a recession - and this is my family's 10th recession in banking - you can't sell a loan, even a performing one, in order to raise cash. A government bond, on the other hand, is liquid."

In the 1960s that point of view was the conventional wisdom. Between 1960 and 1980, however, the loan-to-deposit ratio for U.S. banks rose from 51% to 85%, according to FDIC data. It crossed 100% in 1997, and by 2007 the loan-to-deposit ratio for U.S. banks had hit 113%, which meant that banks were borrowing money to make new loans.

By the time Fitzgerald started recruiting for Chain Bridge in 2007, the consensus about loan-to-deposit ratios had changed so radically that most of the folks Fitzgerald interviewed thought he was nuts. "All the loan officers I was talking to told me, 'Oh, no, you'll get a higher yield on loans than if you just buy bonds. The name of the game is, How many loans can you put on the books?'" says Fitzgerald. "Well, those bankers weren't in the business in the early '90s, and they certainly weren't around in the early '80s. They were behaving as though we'd never have another recession."

Most banks are so illiquid right now that they have to borrow money to meet withdrawals, he says: "You can see right there why we've had the credit crunch."

At the end of last year Chain Bridge actually had less than a third of its deposits allocated to loans. Fitzgerald felt there was better value in Treasury bonds, high-grade corporate bonds, and taxable municipal bonds than in loans, and the strategy seems to be paying off. Chain Bridge's initial business plan assumed that it would take three years for the bank to turn a profit, but Fitzgerald says he's "cautiously optimistic" that it will do so in 2009 and open a second branch in 2010.

According to FDIC data, Chain Bridge's net interest income - which is basically the difference between what it's paying depositors and what it's earning on loans and investments - was $2.1 million in the fourth quarter of 2008, up from $356,000 during the same period in 2007. Total assets rose from $55 million to $127 million.

***

While Chain Bridge is off to a good start, Fitzgerald believes his bank would be even further along had the FDIC and his former colleagues in Congress not essentially suspended the free market for banking last fall. He was particularly irritated by the decision to temporarily raise the limit on FDIC deposit insurance from $100,000 to $250,000 and to extend the FDIC guarantee to non-interest-bearing accounts.

Before those FDIC moves, Chain Bridge was experiencing its strongest deposit growth: Deposits doubled, from $62 million to $123 million, between June and September 2008 as depositors fled weaker banks. "The reason we got into this situation is in part that people didn't care what their bank's balance sheet looked like because their accounts were FDIC-insured," says Fitzgerald.

By not allowing more bad banks to fail, and more good banks to gain market share, Fitzgerald believes the government is creating a banking system that ensures the survival of the not-so-fit at the expense of the fit. "They've only closed about 50 banks," Fitzgerald says of federal banking regulators. "During the S&L crisis of the '80s and '90s, we closed about 1,300 banks. By removing that excess capacity in the industry and by removing the zombie banks in the '80s and early '90s, they made the banking system healthier for those banks that withstood the early-1990s recession."

"Look at Northern Trust," Fitzgerald continues, referring to the Chicago bank that has weathered the current credit crunch about as well as any depository institution. "In 1929, Northern Trust had $50 million in deposits. By 1933 or 1934 it was a $250 million bank. During the Great Depression it thrived while other banks were being closed, because it had a strong balance sheet. It actually ran ads in the Chicago Tribune showing that its assets were in government bonds, not loans."

Because of the higher limits on FDIC insurance, depositors now have even less incentive to police their banks. The FDIC has compounded the problem, Fitzgerald says, by hiking fees in ways that hurt small banks - which rely more heavily on FDIC-insured deposits for funding - more than the large banks that caused the credit crisis.

"Why are you putting the burden of paying for the FDIC on the community banks that are funded the old-fashioned way, by core deposits?" Fitzgerald says. "The burden for funding the FDIC should be put on the banks that operate with riskier wholesale funding - the Citigroups of the world. If you're too big to fail, maybe you need to have higher capital requirements. Maybe you need to pay higher risk premiums on FDIC deposit insurance. Maybe what you pay [for FDIC insurance] should be based on your total assets instead of on your deposits."

FDIC chief Sheila Bair counters that making weak banks pay to replenish the deposit insurance fund isn't feasible. "In any insurance system premiums paid by healthier members are supposed to help cover the losses of weaker members," Bair said at a meeting of the Independent Community Bankers Association in March.

***

Fitzgerald lays some of the blame for what he sees as the wrongheaded response to the banking crisis at the feet of Barack Obama, the man who succeeded him in the Senate. "I served with Barack in the [Illinois] state senate in Springfield," says Fitzgerald, who was a vocal supporter of John McCain during the presidential campaign. "I chaired the government operations committee when Barack was the ranking Democrat. It was very clear to me that he was a very bright and hard-working and talented individual. However, his sweet spot is constitutional law. It's not the economy."

The dig is not sour grapes. Fitzgerald was never cut out to be a lion of the Senate. He chose not to seek reelection in 2004 for the seat Obama eventually won. Fitzgerald claims it was family concerns that kept him from seeking reelection. Between his weekday work in Washington, where his family lives, and his weekend trips back to Illinois to press the flesh with constituents, he says, "I never saw my wife or son." His 16-year-old son, Jake, is a now a pitcher on the baseball team at Washington's prestigious St. Albans School. Fitzgerald says that when Jake was in Little League, he was rarely able to make it to his games.

He also had a hard time with the horse-trading that is part of being a legislator. Indeed, Fitzgerald's most important legacy as a senator is the aforementioned nomination of Patrick Fitzgerald as U.S. attorney for Chicago. Patrick Fitzgerald would subsequently help bring down the Republican Illinois governor, George Ryan, on corruption charges and also cause countless headaches for the Bush administration after being named special prosecutor in the Valerie Plame CIA leak case. (Of course, Patrick Fitzgerald's latest target is a Democrat: Rod Blagojevich, the former Illinois governor, who was indicted on corruption charges in April.)

Presidents customarily defer to senators in their party with regard to nominations of U.S. attorneys. And as the lone Republican senator from Illinois, that responsibility fell to Fitzgerald in 2001. Worried about corruption in state politics, Fitzgerald took the highly unusual step of seeking a U.S. attorney from outside Illinois. "I wanted somebody who was not under the thumb of the powers that be in Chicago," says Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald asked FBI director Louis Freeh for a recommendation, and it was Freeh who suggested Patrick Fitzgerald, a no-nonsense terrorism prosecutor in Manhattan's U.S. Attorney's Office. When word got out, Fitzgerald says, Bush's White House chief of staff Karl Rove told him he had to select someone from Chicago - a directive Fitzgerald obviously ignored. But the press reacted so favorably, Fitzgerald says, "the White House was just inclined to go along."

Fitzgerald also alleges that the Speaker of the House at that time, Dennis Hastert - a Republican from Illinois - at first asked the White House to let him make the nomination instead of Fitzgerald. Hastert was close to Gov. Ryan - who is today serving a 6½-year sentence for corruption - and Fitzgerald believes that Hastert wanted to install a U.S. attorney who "would put a kibosh on the Ryan investigation." Hastert denies Fitzgerald's claims. Rove declined to comment.

Today the banker-turned-senator-turned-banker thinks the major problem with the Obama administration's approach to the recession is the misguided belief that stimulating the economy and fixing the banking system are compatible goals. "They're not," says Fitzgerald, who contends that banks need to be making fewer loans, not more.

Fitzgerald is particularly critical of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency for not requiring banks to keep some share of their deposits and assets in liquid investments. "The OCC will not get after them," says Fitzgerald. "That's because the OCC wants the banks to support President Obama's stimulus program and lend as much as possible."

OCC deputy comptroller Timothy Long counters that the regulator does take liquidity risk seriously. "Liquidity risk has always been a significant focus of OCC supervision," says Long. But while the OCC closely monitors bank liquidity, ultimately "the responsibility to manage this process lies with management and the board of the individual bank."

If you're Peter Fitzgerald, that goes without saying. ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More