My death-defying climb with Jim Collins

Scaling a 1,000-ft rock face with the management guru, our writer finds out what makes him tick.

|

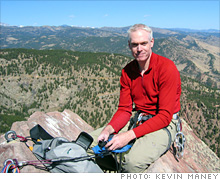

| Author Jim Collins. |

NEW YORK (FORTUNE) -- It's 7 a.m. when I park in front of Jim Collins' house in Boulder, Colo. He's already out front, slim and wiry, his 50 years given away by nearly-white hair. Collins looks up from sorting piles of hooks, harnesses, ropes and cantilevered clasps. "Want to see where we're going?" he says. Collins is energized, caffeinated, enthused -- which seems to be his natural state. If he were a dog, he'd be a Jack Russell terrier.

He lives in a middle-class neighborhood of circa-1900 stone homes. Growing up in Boulder, Collins delivered newspapers to the house he now owns. He points up over the rooftops at the First Flatiron, a 1,000-foot rock face set against the blue sky.

Collins has told me about the joys of rock climbing since we met 18 years ago -- before his bestellers "Built to Last" and "Good to Great" and long before his just-out "How the Mighty Fall;" before Collins had fans like Steve Jobs and Jeff Immelt; before his advice was sought by companies from Starbucks (SBUX, Fortune 500) to start-ups. Collins is a rock climber the way Bruce Springsteen is a Jersey boy or Anna Faris is a blonde. It's part of Collins' identity. It informs his thinking.

Which I'd always found intriguing -- from a safe distance. I never, ever wanted to go rock climbing with him or anyone. I'd never climbed anything harder than a chain link fence. But I recently agreed to try what I think I termed a "baby climb" with Collins -- and he chose the Flatiron looming above. We return to the house and see Jim's wife, Joanne. "You'll enjoy the climb," she says. "It's not that hard." She's a former World Ironman champion. So I don't believe her.

Collins hands me half the climbing equipment, and we set off toward the base of the First Flatiron, less than a mile away. He talks as we go, first about Tommy Caldwell, the Tiger Woods of rock climbing, who scaled the 3,000-foot Nose of El Capitan with Collins for Collins' 50th birthday. Collins segues into a riff about the economic crisis. He explains that his latest research, which will inform his next book, shows that innovation isn't the key to bouncing back from the recession. Discipline is.

"Our natural response when the world spins out of control as Americans is we have to do something new and different," Collins says. "Actually, things could be spinning out of control because we lost discipline. It's very hard to argue we got into this financial mess because we lacked innovation." It's a jab at hedge fund managers and their whizzy formulas, the real villains, in Collins' mind.

At the base of the cliff, we drop our packs and step into harnesses. Collins attaches a rope to mine. He'll free climb 150-feet up, anchor in, and then keep the rope taut as I climb, so that if I slip on the rock face I won't go much of anywhere.

Collins pulls out a pair of yellow Motorola walkie-talkies. He turns them on. They don't work. Motorola is one of Collins' big disappointments. In "Built to Last," Collins and co-author Jerry Porras identified Motorola (MOT, Fortune 500) as a great enduring company. Motorola is now a train wreck. In "How the Mighty Fall," Motorola is one of the fallen. Collins mutters something derogatory about Motorola products, leaves his yellow walkie-talkie dangling uselessly from his harness, and starts climbing.

About 30 feet up, he yells, quite loudly, "Oh, this is super good fun!"

Yeah, he can be kind of a nerd.

Collins' parents divorced when he was in sixth grade, and his mother remarried less than two years later. Collins coped with the changes by diving into school and books. His new stepfather signed him up for rock climbing lessons, not all that unusual in Boulder. "I think I whined something along the lines of, 'I'd rather study,'" Collins recalls. "He thought it would be good for me." Collins immediately loved it. He loved the physical challenge. He loved that gravity doesn't accept excuses. There is a black-and-whiteness about climbing -- you either get up the mountain or you fall down -- that seems to be a relief to Collins.

He has done big climbs around the world. He climbs near Boulder as a quick break. This rock face, which we'll inch up over the course of a few hours, he'll sometimes speed-climb solo in about 18 minutes. "It's one of the few things I do that completely puts you in the here and now," he tells me. "There's no past, no future, no deadlines, no projects. Just you and the rock and the ten feet around you. It's really good for your brain."

This I now understand. The First Flatiron is angled slightly from 90 degrees. That makes it seem a little less scary from the bottom, until I start up. The holds are tiny and hard to find. I support my weight on outcroppings smaller than a big toe. Only a few feet up, I get crazy scared and wonder if it's kosher to grab the rope tying me to Collins. But we make it to a ledge 500 feet up, and sit eating power bars, Boulder below looking like a Google Maps satellite photo. Between bites, I ask Collins how rock climbing affects his work.

"I see climbing metaphors almost everywhere," Collins answers. The financial collapse is one example, he explains. Investment banks thought they had magic formulas to beat gravity and took fantastic risks so they could climb faster, failing to use common safety mechanisms like anchors. When they slipped, nothing was there to stop their fall. "People took risks that were lethal to their enterprises," Collins says. "It's hard for me not to take my climbing brain and look at this stuff."

We get onto the topic of his next book. He and Morten Hansen of the University of California, Berkeley, just finished seven years of number-crunching research into why some companies do well during turbulent times, and others don't. This is how Collins came to the conclusion about discipline and innovation. When an industry or whole economy goes to hell, highly disciplined companies like Intel (INTC, Fortune 500) or Southwest Airlines (LUV, Fortune 500) come through it and even gain strength. Companies that rely too much on innovation hit a wall and crumble.

Collins is jubilant that the findings are directly counter to an American business culture that worships innovation the way ancient Egyptians revered Ra. But Collins is still thinking through the results and hasn't yet started writing.

In the meantime, "How the Mighty Fall" is fueling his fan base. Which brings me, here on the ledge, to ask Collins: Do you understand what a big deal you've become?

He laughs. A lot.

"I don't, and I'm not sure I want to," he finally says. "I sort of feel pretty much the same. Actually, it's more that I feel like I live on the edge of complete irrelevance."

The guy is the J.K. Rowling of management literature, and he suffers from self-doubt like the rest of us. Which is funny because I always felt Collins was one of the most assured people I'd ever met. The man rarely stammers or searches for answers. He comes to conclusions and fires them like mortar shells. When I asked earlier in the day what should be done about the U.S. automakers, he blurted, "They screwed up; they should die."

He seems to have a bedrock personal life: 29 years married to Joanne; 14 years in the same house in his hometown; the money to do what he wants. And his fans are legion. I have seen a hotel ballroom full of swaggering CEOs listen to Collins with the awe of first-graders getting a lecture from a fully-suited fireman.

Then again, you open up any driven person, and you're likely to find insecurity lurking inside. Happy people get complacent. As Collins wrote in his mega-seller's opening line: "Good is the enemy of great." Collins also realizes he has set himself up for criticism. "Good to Great," published in 2001, has sold 3 million copies, making it the best-selling hard-cover business book ever, but some of Collins' good-to-great companies turned into disasters. Circuit City liquidated. Fannie Mae (FNM, Fortune 500) helped bring the economy down. To some readers and business leaders, Collins has to prove himself all over again.

If you want to get an instant sense of vertigo, go to YouTube and type in "El Capitan climbing." The granite formation in Yosemite National Park is taller than two stacked Sears Towers. The magnificent prow in the middle is the Nose, and the route up said Nose is considered one of the premier -- and hardest -- climbs on the planet. A very good climber can do it in four days, spending nights on ledges. Tommy Caldwell has climbed the Nose solo in less than 12 hours.

When Collins turned 48, he started thinking that he wanted to do something "life-affirming" for his 50th. He worked out with a climbing coach in Boulder, and casually mentioned to the coach that one of his dreams, something he never thought he'd do, was to climb the Nose of El Cap in a day. The coach is one of Caldwell's best friends, and relayed to Caldwell what Collins said. Caldwell, in turn, had long admired Collins' books, and jumped at the chance to train and do the climb with him.

Collins probably could not have conquered the Nose of El Cap had he not written "Good to Great." The book is famous for its catchy concepts familiar to much of the business landscape. "First Who" is the idea that choosing the right people is more important than anything. "The Stockdale Principle" says that you have to face the brutal facts of reality, but believe you will persevere. "The Flywheel" is about constantly building momentum.

Collins says he decided to do El Cap only because Caldwell agreed to get involved. "I had THE 'First Who' to go train with and have this experience with," Collins says. About 18 months before the El Cap climb, Caldwell started preparing Collins. They worked out a training roadmap, and Collins started pushing on his flywheel. On the cliffs around Boulder, Collins built up to climbing 1,200 feet in a day, then 1,500, then 1,800. Some days, he'd work out for three hours, ride his bike 40 miles, then climb for eight hours. "He was so over prepared it was ridiculous," Caldwell told me, laughing. "As Jim does with everything, he took it to the extreme."

Through all this, Collins kept working. Unable to move much more than his typing fingers and eyeballs on recovery days, Collins would sit and write or crunch data. Collins and Caldwell made trips to Yosemite to scout El Cap and do other big climbs in the park. So he scheduled meetings at Yosemite with research partner Hansen, who lives in San Francisco. "I'd drive to Yosemite and we'd go on some walks and talk and we did our work, so it was no problem," Hansen says. "We're both organized individuals. Although, Jim is a little more extreme."

The data nerd in Collins played a role, too. He wanted to pick the perfect time to go, with a window of opportunity in case of a storm blew in or he got a stomach flu. On a government Web site, he found 100 years of Yosemite daily weather data, downloaded it, and dumped it all into a spreadsheet. He crunched all the numbers to find the window of time when temperatures start to fall and storms almost never blow in. "That window is September 15 to October 7, " Collins says. Then Collins looked for the date of the full moon in that time frame. "If I was going to climb partly by headlamp, I wanted a full moon in my favor," he says. The full moon would be out on Sept. 26, 2008. That became his target date.

The weather data exercise "taught me a lot about Jim," Caldwell says, again sounding amused. "Jim is really Jim in everything he does."

It takes a while, but Jim and I finally conquer the Flatiron and stop on the summit to snap pictures of each other. The back side of the First Flatiron drops straight down about 200 feet to a trail, which we could hike back around to the front where we'd started. I have a slight are-you-kidding-me moment when Collins tells me to lean back off the cliff so he can lower me to the trail.

Our climb finished, the two of us lounge in the sun, backs against a couple of rocks in the park below the Flatiron. It's about noon on a perfect, cloudless day. Collins dives into stories about the El Cap ascent.

He and Caldwell made decent time and neared the summit at about 6 p.m., 20 hours after they started. Collins by that point had been up about 36 hours. Between the physical exhaustion and lack of sleep, Collins says he felt like he was slipping into a state he'd never experienced. He gets reverential as he tells the story:

"I stopped about 30 feet from the top," he says. "And something overcame me, thinking I should just take this in. The sun to my left was going down over the central valley, a giant orange fireball, everything bathed in that end-of-day pink and orange. I looked down and if I dropped a quarter, it would've gone 3,000 feet without hitting anything. I looked to my right, and there was the full moon coming up for the night.

"And I had this amazing experience of...um...the only word I can use is just gratitude. It was a five-minute experience that was absolutely perfect, and it took two years to create, and it just washed over me."

We walk the rest of the way down the trail and across the park, the climbing gear around our waists and over our shoulders clinking with the movement. I feel like I understand the attraction Collins feels for rock climbing...and yet don't. The adventure, the physical act of climbing, the focus, the beauty -- I get all that. The fear, I don't get and didn't like. Climbing with Collins took me part way toward comprehending his passion, but not all the way.

At his house, Joanne is gardening. She and Collins get into playful banter about how she puts up with his climbing except that Jim is not allowed to come home and bleed in bed. The next-door neighbor walks over and complains about people breaking the sprinkler heads sticking out of his lawn. Collins and I say our good-byes and he disappears inside. All of it becomes one -- the books, the house, the life, the rocks beyond, coalescing into a man unlike any I've encountered on the business landscape. ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More