Jamie Dimon vs. Sandy Weill

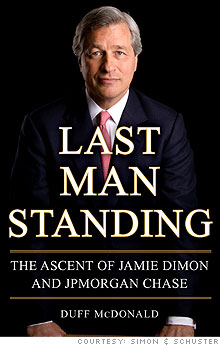

In an excerpt from his soon-to be-published book, Last Man Standing, author Duff McDonald sheds new light on one of the most complicated personal relationships in modern American capitalism.

|

| Author Duff McDonald |

NEW YORK (Fortune) -- In the annals of great business partnerships, few have achieved as much success -- or provided as much drama -- as that of Jamie Dimon and Sandy Weill. Starting in 1982, the two men worked side-by-side for sixteen years, a period during which they built a financial behemoth that included Smith Barney, Travelers and finally Citicorp. And then, in 1998, it was over. Just weeks after their greatest deal ever -- the merger of Travelers Group and Citicorp -- Weill fired his longtime prot�g�, surprising colleagues, Wall Street, and Dimon himself.

The personality clash that came to a head in a shoving match at a West Virginia resort called The Greenbriar has proved to have had a huge impact on the landscape of high finance. What if Dimon had remained in Weill's good graces and gone on to succeed him at Citigroup? Where would Citigroup, currently a bank crippled thanks to investments in complex illiquid securities, be now if the risk-averse Dimon had been at the helm during the years leading up to the financial crisis? And where would JPMorgan Chase be if Dimon had never left Weil's side?

Despite feeling a profound sense of betrayal at the time -- one that has hardly subsided in the decade since -- Jamie Dimon chose to take the high road, and largely kept his thoughts on the end of the working relationship to himself. Until now. In this two-part excerpt, appearing today and tomorrow from journalist Duff McDonald's new book, Last Man Standing, Fortune offers up new information on their time together, the dramatic end to their union, and the fact that even today, the two men have largely been unable to bury the hatchet.

--Editor's Note: This story contains profanity.

Jamie Dimon began working for Sandy Weill when he was fresh out of Harvard Business School in 1982. At that point, Weill was already a minor legend on Wall Street, having built and sold Shearson Loeb Rhoades to American Express. Just 26 when he signed on as Weill's assistant, Dimon was no shrinking violet either, and practically demanded through hard work and a forceful personality that Weill treat him as a junior partner. Four years later, when Weill began building his second empire at Commercial Credit in Baltimore, Dimon was right there beside him.

Working with a group of veteran executives, Dimon soon earned the nickname "the kid." The combination of Dimon's shrewd number crunching and Weill's vision and salesmanship put the two men on course to make a series of bold acquisitions, starting with the foundering financial services conglomerate Primerica, which owned both Primerica Financial Services and the investment bank Smith Barney. (They would later add Travelers insurance to the mix.) In March 1990, Weill made Dimon an executive vice president at Primerica.

During the early Nineties, Dimon was closer to Sandy Weill than he'd ever been before. If a visitor dropped by Weill's house in Greenwich, Connecticut on a Sunday morning, Dimon's Volvo wagon was invariably parked in the driveway, the two men already hard at work by 7:00 a.m. Three months after adding the EVP title at Primerica, Dimon also added those of executive vice president and chief administrative officer of Smith Barney.

By September 1991, Weill decided to officially recognize what much of Wall Street had finally come to appreciate, that Jamie Dimon was a driving force at Primerica. Weill named Dimon, just 35 years old, president of the company, relinquishing the title to his prot�g�. Weill had a peculiar style of mentoring, however. While he regularly rewarded Dimon, he often tested him by forcing power-sharing arrangements on him.

After making him chief administrative officer of Smith Barney in April 1991, for example, Weill then hired Bob Druskin away from Shearson Lehman, where he had been CFO, to be co-CAO with the younger man. Over the years Dimon would again and again find himself pitted against Wall Street heavyweights: first Frank Zarb, the former "Energy Czar" during the Ford Administration who was the chairman and CEO of Smith Barney from 1988 to 1993 and then veteran investment banker Robert Greenhill, who Weill installed as chief of Smith Barney after Zarb. The contradictory signals would eventually drive Dimon to an act of rebellion, but in the early part of the decade, he still held his boss on a pedestal, and took what he was given without much complaint.

It was in this period in Dimon's career that Weill began to develop his own doubts about Dimon as a successor. The reasons for Weill's losing faith in Dimon depend upon which associate of the two men you ask. Some feel it was Dimon's growing profile that irked Weill; others feel it was an incident involving Weill's daughter.

When a picture of the two men appeared in the New York Times showing Dimon in the forefront with Weill standing distantly behind, Weill was outraged. The headline of that July 1995 New York Times article was "Becoming His Own Man: At Travelers, Weill's Prot�g� Is On the Move." Despite the fact that Weill had endorsed the idea of the story, many viewed the seemingly innocuous celebration of Dimon's talents as a critical turning point in his relationship with Weill. Weill came to see the article as an unforgivable transgression, even if Dimon obviously had nothing to do with the choice of photos in the story. "It's not good for Jamie to be getting this kind of publicity," Weill's wife Joan mentioned to Dimon's mother Themis in passing. (The two families had been friends since the 1970s, when Dimon's father Ted had worked for Weill.)

While Weill himself made several glowing remarks about Dimon in the Times piece, he was taken aback by the suggestion from a board member that implied Dimon -- not Weill -- was the central figure at Travelers. Joseph Califano, a Travelers director, had actually said exactly that: "He runs Smith Barney," said Califano, adding that Dimon was more and more the driving force at Travelers as a whole. Several people told Dimon that the story was going to cause him problems. They were right. Weill barged into a meeting the next day. "Who the fuck told Joe Califano to say that? And who chose that photo?"

Still, Dimon failed to initially recognize the shift in his boss' perspective. "I was still a little bit of a kid," recalls Dimon. "Weill's PR people orchestrated it. He knew about it. He knew better, and I didn't. But I don't think it was really about the picture. He looked more like a proud father in it than anything else. It was about Califano's quote. All of a sudden there was the question: 'Is Jamie really running this place?' I think that was what got to him."

And then there was the daughter. In 1994 Dimon had welcomed Weill's daughter, Jessica Bibliowicz, to Smith Barney as an executive vice president in charge of sales and marketing in the company's $55 billion mutual fund division. Bibliowicz would report to Dimon and not her father. In January 1995, Dimon named Bibliowicz chairman of the company's mutual fund operations, then the ninth largest in the country. He'd even pushed her ahead of a candidate favored by the company's head of asset management, Jeff Lane, taking some political heat in the process. But in reality, Bibliowicz only ran the mutual fund sales department, which had a mere 18 people in it. Despite the loftiness of the title, she didn't oversee money management, operations, or finance for the fund group.

Friends since childhood, the relationship between Dimon and Bibliowicz began to fray the next year, when Dimon pushed for the company to sell no-load mutual funds in response to the success of Vanguard and other no-load fund companies. Bibliowicz resisted the idea, arguing that the company should stick to its own internal funds -- brokers were far more motivated to sell them, after all, given the commissions -- and Weill himself sided with her in discussions on the subject. Dimon eventually won the debate, and in July 1996 Smith Barney was the first Wall Street broker to sell no-load funds.

Dimon increasingly became convinced that Bibliowicz's strengths were limited to "soft" skills, like marketing, and that she lacked a thorough enough understanding of the numbers of the business. He began to criticize her openly, alienating Bibliowicz and irritating Weill.

Not long after, in February 1997, Dimon committed what Weill regarded as another ignominy upon his daughter. He named three executives to the Smith Barney planning committee -- including Smith Barney's general counsel Joan Guggenheimer -- and excluded Bibliowicz. Weill's daughter felt it was a message directed squarely at her: A woman, yes, but not you. Guggenheimer, it should be pointed out, managed hundreds of people compared to Bibliowicz's 18. From Weill's perspective, though, it was an unforgivable slight. His reaction was one of near-hysteria.

The final, irreconcilable breach in Dimon and Bibliowicz's relationship came when Dimon actually acceded to Bibliowicz's ambition. When she asked him how she could get ahead in the company, he asked her what she aspired to. "Well, I'd love to run Smith Barney one day," she replied. Dimon told her that if that were ever going to happen, she needed experience in the retail side of the business. He then called Mike Panitch, who oversaw the retail branches, and asked him to put her in charge of one of the company's four divisions -- East, Midwest, Southwest, or West.

Panitch offered her California, offering the rationale that the other three states in the West division -- Nevada, Montana, and Idaho -- added too much travel and headache for someone settling into a new position, and assigned them to another division head. Dimon signed off on the arrangement as well, thinking that it wouldn't be a comedown for Bibliowicz, considering California's 2,100 or so brokers versus 2,700 for the four states combined. He was wrong. Bibliowicz felt slighted. Weill exploded when he found out. "You insulted her!" he raged to Dimon.

Ultimately, Bibliowicz decided to resign. Dimon told Bibliowicz she was doing the right thing. "Honestly, Jessica, you're not going to be treated properly around here anymore," he said. "Not everyone is telling you the truth. Not everyone is telling your father the truth. He's gotten too involved. You need your own life outside this company."

Years later, Weill still stews over how Dimon handled the situation. "I've said this to him in the past, and he doesn't like me to say it," recalls Weill. "I think Jamie built terrific loyalty from some people and developed a group of people who he really had great relationships with. Others bumped into that, and those that bumped into that, their fate was not great."

The last straw came for Dimon and Weill came with the arrival of Deryck Maughan to their growing financial services company. Maughan, a debonair Englishman, had been handpicked by Warren Buffett as CEO of Salomon Brothers after Buffett purchased 20% of the firm in the wake of a 1991 Treasury bond scandal. On September 24, 1997, it was announced that Travelers was buying Salomon for $9 billion. And Dimon now had a new bone to pick with his boss.

Although Dimon had been effectively running Smith Barney by himself since Greenhill's departure, the Salomon deal brought Maughan along with it, and Weill told Dimon that he had decided to make Maughan a co-CEO of Smith Barney alongside Dimon. Dimon was enraged. He reminded Weill that in previous negotiations with Salomon, Weill had indicated that Dimon would have complete control. But now, with the deal done, Weill refused to budge on the matter.

When Travelers had flirted with the idea of buying Salomon the previous year, Weill had told associates that he would fire Maughan if the deal were completed. To view him now as the answer to his problems was a stunning about-face. Within Travelers, there was a long-running joke about Sandy Weill's fickleness. If you walked by Weill's office and saw a new face, you might be moved to ask, "Who's that?" The answer: "That's Sandy's new best friend." Maughan would continue to become closer to Weill, often hanging around his office, while Dimon gave Weill a wide berth -- a tactical error that would create problems for him when Weill attempted the biggest merger of his career.

Read Part Two: When a banking feud got physical

Part one of two parts excerpted from Last Man Standing: The Ascent of Jamie Dimon and JP Morgan Chase, by Duff McDonald, to be published by Simon & Schuster on October 6, 2009. © Duff McDonald ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More