The Informant: 'I thought I was bulletproof'

Former ADM exec and whistleblower Mark Whitacre talks about watching his life on screen in Steven Soderbergh's dark comedy, 'The Informant!'

|

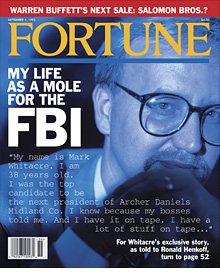

| Whitacre first made public many of the details of his story in the Sept. 4, 1995 issue of Fortune. |

NEW YORK (Fortune) -- Most people, if they know of Mark Whitacre at all, remember him as a whistleblower. In the early 1990s, the Archer Daniels Midland vice president turned FBI mole helped bring the company to its knees by wearing a wire for three years to expose its price-fixing scheme.

But the tale grew bizarre once ADM (ADM, Fortune 500) and the FBI discovered Whitacre had stolen $9 million from the company and compulsively lied his way through the whole case -- so much so that Fortune became a victim, too, publishing Whitacre's lies that an FBI agent had ordered him to destroy evidence and swung a briefcase at him, bruising his arm.

Director Steven Soderbergh found the Whitacre brouhaha so intriguing that he turned it into "The Informant!", which is in theaters now. So Fortune decided to go back to Whitacre and find out what he thought of the movie. (In a climactic scene toward the end of the film, Matt Damon, as Whitacre, tries desperately to use the fact that Fortune magazine--"THE Fortune magazine!" he says -- published these "facts" as proof that he's telling the truth.)

Whitacre, 52, talked about being diagnosed with bipolar disorder, spending almost a decade in prison, and lying to our publication.

What did you think of the movie?

I found it pretty good, actually. I understand Steven Soderbergh's reason for not wanting to do it as a serious movie. Shortly after he bought the rights to "The Informant!" -- he told us this at the premiere last week -- "The Insider" came out. And that was this serious whistleblower story, and he just didn't want to do another serious story. He thought it would be too much like "The Insider." So he decided on a dark comedy.

He flew us to Burbank and showed the movie to us in June, right when they had the final movie in the can. At the showing, it was pretty tough to relive some of that. Some of the crazy things I did, it's just -- to work for the FBI and take $9 million dollars at the same time. The things I did back then were just bizarre, and I think that's why they were able to make it into a dark comedy.

So you weren't upset that it was billed as a comedy?

Not really. I thought they were pretty sensitive to the mental illness part. I felt like most of the comical parts were really in the trailer.

When we met Matt Damon last week, that's one of the things he was really concerned about. He said, "I hope I really portrayed your plight and mental illness in a sensitive way." And I think he did. I mean, they were making fun of lots of things I did, and rightfully so, but I don't think they were making fun of my bipolar disorder.

How do you feel about Matt Damon playing you?

I think he did a great job. It had to be a tough part to play, especially with all those bipolar thoughts and manic behavior, and all those voiceovers.

[Screenwriter] Scott Burns talked to a psychologist or psychiatrist, someone who understood bipolar, and tried to describe to him what an undiagnosed bipolar person would be thinking. That's how they thought of all the voiceovers. They were trying to make a point that I would be thinking of trivial things at very serious moments, in serious meetings. I think the movie is more about untreated and undiagnosed mental illness than the price-fixing case.

A lot of the movie hinges on your compulsive lying.

Well, I definitely did a lot of that. Embellishment is one of the symptoms of bipolar; grandiosity, poor judgment on financial matters -- that's an obvious one. Usually, if bipolar is untreated under severe stress, suicide is a normal outcome. I attempted suicide twice.

They did have the suicide, one of the attempts, in the original movie, and they took it out. Soderbergh said he took it out because it's a lot for the family to live through, and with it being a dark comedy, a suicide attempt just wouldn't fit.

I thought I was bulletproof -- being able to stay at the company, be made the CEO. That's delusional. I mean, even if my actions weren't related to bipolar, I obviously had some serious issues that I had to deal with. I went through lots of years of seeing a psychiatrist two or three days a week, and I was heavily medicated for a couple years.

You spent almost nine years in prison. What did you learn there?

I learned my family was the most important thing in my life. My wife moved to every state I was located and came every Friday, Saturday, and Sunday for eight and a half years. Basically, Monday through Thursday I'd be waiting for Friday night, and she'd come all day Saturday and all day Sunday. And I don't mean for an hour or two. I mean from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. That's definitely not the norm. I mean, the divorce rate in prison is 99%, and the divorce rate in society is over 50%. I'm very lucky, and she's really what kept me alive. My wife, she's definitely a trooper.

I started to look at all the things I did. That's pretty depressing at first. And maybe part of it wasn't because of my mental illness. I think I was the youngest corporate vice president at age 35. I got that promotion the week before I met the FBI, so I was all about greed and power.

I definitely lost my balance. I took my family for granted and all I did was work, work, work and travel, travel, travel. It's good to be ambitious, but I was definitely hyper-ambitious, to the point where it wasn't healthy. It probably made my mental illness even worse.

I had a sense of entitlement and felt like anything I took was mine; the company owed it to me because I worked hard enough. I wasn't worried about them firing me when I was taking money, because I knew if they ever came to me and said, "Look, Mark, you took $9 million," I'd say, "Wait a minute, you guys are stealing hundreds of millions on the price-fixing scheme every month." So I wasn't worried about the company turning me in. That was the warped thinking I had back then. But once they knew I was the informant, then they had no reason to hold back.

What's the status of the presidential pardon you requested?

The pardon really won't happen yet because a pardon requires five years out of prison. Now the FBI and even one of my former prosecutors have tried -- tried to go around the guideline to apply for a pardon. They tried to show, because of my mental illness and because of the bigger case, that I gave them more compared to what I did wrong, but I'm not even three years out until this December. But when I hit that five-year mark, we're really going to push it hard. Really, the pardon doesn't really do -- I mean, my family stayed with me, and I'm employed.

So how did you get your current job as COO of Cypress Systems, since you're a convicted felon?

Luckily, people stayed with me. That's not the norm. It happened to be the professor, which I did my Ph.D. under at Cornell University, where I graduated from 25 years ago. One of my professors was doing some research in cancer alongside Cypress, and he does a lot of selenium work, and that's what I have my Ph.D. in -- selenium biochemistry. And there's not many selenium biochemists in the world, maybe 100 or 200. It helped me that so few people had expertise in that field.

So that professor mentioned my name to the CEO of Cypress, a small biotech. In 2001, the CEO came and visited me in prison. He was also very involved in prison ministry in California and helping people re-enter society. He got to understand the case, and that made him understand my mental illness better. He knew my selenium background was strong, and one thing led to the next. I got out on December 21, 2006, and I started work on the 22nd.

So overall do you think you did the right thing?

Well, it was really my wife. She made the decision that if I didn't tell the FBI about the price-fixing, she was going to. So in reality she did the right thing and not me. I see her more the whistleblower than myself. She had the moral compass.

Both of us feel now after what we went through that we were being na�ve that we could survive this. It's been too much loss, too much chaos. But on the other hand, there are some good things. I have a more balanced life today, and my bipolar disorder was diagnosed. And maybe ADM would still be price-fixing ...

Anything else you'd like to add?

I'd like to apologize to Fortune magazine. A lot of the stuff [then-Fortune staffer] Ron Henkoff wrote in his cover story, ["So Who is This Mark Whitacre, and Why is He Saying These Things About ADM"], in September 1995, there was a lot of accuracy, and that was from the heart. If you look at that one, most of the things I said end up still being true today.

But after that, [on later stories], some of the things I did tell him weren't true. I told him the FBI agents did this and that. I apologize for lying to your group. I know it had to be -- those stories based on what I'm saying and then, a couple weeks later, I'm saying stuff didn't happen, and Fortune already had the article out -- I mean, it wasn't a good situation.

I thought a lot about that in prison [voice starts to quiver]. I really did, you know, about the chaos I caused for other people because of my actions. Fortune was definitely on that list. Please apologize to your editors, too. That was a big mistake and I'm sure it caused some chaos for you all. ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More