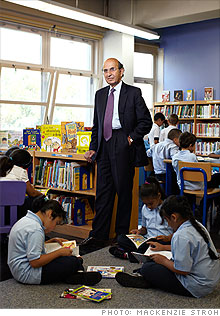

The CEO educator

New York City education chief Joel Klein talks about improving inner-city schools, competing globally, and how Jack Welch helps him groom his leadership team.

|

| Joel Klein, school chancellor of New York City public schools |

(Fortune Magazine) -- Joel Klein's title is New York City school chancellor, but he's really a CEO. He oversees America's largest public school system -- 1.1 million students -- with more authority than his counterparts in most other major cities, thanks to a landmark 2002 law that was just renewed for another five years.

With power comes accountability, and Klein has delivered impressively: Test scores have improved, graduation rates have risen, and the racial and ethnic achievement gap has narrowed.

Klein's progress in a chronically poor system has been so remarkable that two years ago his department won the Broad Prize for Urban Education, America's top education award. When Arne Duncan was confirmed as the new U.S. education secretary earlier this year, his first visit was to Klein.

Klein is a product of the schools he now runs. He attended New York City public schools for 12 years, then went to Columbia University and Harvard Law School.

He clerked for Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell and eventually became the Justice Department's antitrust chief under President Clinton. In that role Klein launched a major antitrust suit against Microsoft -- yet founder Bill Gates' foundation has since given millions to Klein's school system.

Klein was the CEO of Bertelsmann's U.S. operations when New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg asked him to become school chancellor in 2002.

As a new school year begins, Fortune's Geoff Colvin talked with Klein about why U.S. education is falling behind globally, how to bring business leadership training to public schools, ways New York City schools transformed Klein's own life, and much else. Edited excerpts:

What's at stake here? We've all seen how U.S. students stack up against those in other countries, and it doesn't look good. Is this a problem that's getting better or worse?

It's getting worse, and it's looking very troubling. You've got the whole set of new countries like China and India with the focus they have on education. Then look at the [30] OECD countries and look at us.

In 1995 we had the second-highest graduation rate. We are flat 10 years later, and we've gone from second place to 16th. Graduation rates in the rest of the competitive countries have gone up 10, 15, 20 points. In Korea, where they're outperforming us dramatically on any math or science test, they have a month more of schooling each year than we do. That stuff matters.

What explains the U.S. decline? As other countries develop economically, they naturally advance in education, but something seems to be going on in the U.S. as well. What's the problem?

It's a question that, until I got in the middle of this, I didn't think a lot about, but now I think about it all the time. You say we all know the numbers, but people don't react to them with passion and a sense that we've got to do something. I think the reason is that they don't impact all of us the same way.

My kids are going to get an education. Your kids are going to get an education. But poor kids -- kids who grow up in challenged environments -- they've gotten the short end of the stick as far back as anyone can remember.

When you have something like 9/11, nobody thinks 9/11 is going to attack different neighborhoods in different ways. We're all in that together -- public safety we're in together. But education is a disaggregated service, and so we're not in it together. In addition, I still don't think most people understand the 10-year-out global challenges we're going to face.

What are they? What's down the road for U.S. global competitiveness?

I spend a lot of time with people in the corporate world talking about these issues. Large global corporations are going to go where the talent is at the price that makes the most sense. They'd like to say we'll hire Americans first, but the world isn't going to allow them to make those decisions.

So in places where they're training up lots of engineers or investing heavily in training up technical expertise -- software designers and so forth -- the business is going to go there.

I see colleagues who are using tutoring services where kids get online with people in India tutoring them in math. This is the challenge. Other countries are not going to wait for us. We're going to have to step on the gas and really accelerate what we're doing.

To what extent is culture a factor? Everybody who has traveled to China and India is blown away by the passion for education you see there, the value everybody in the society assigns to education. In the U.S. you get the feeling that maybe we don't assign the same value to education we did when you and I were in elementary school. Is that a factor?

I think it is. I also think there's not an immediacy about it. There's a belief in most middle-class or affluent communities that their kids are getting a good education.

In fact, they're worried about the stress -- they say there's too much high-stakes testing. But our kids are going to grow up in a world with high-stakes testing at every level, high-stakes challenges in a very aggressive global economy.

We've got to acculturate ourselves to the fact that our kids are going to grow up in stressful, challenging environments, and the pressures of the global economy are going to have an impact on them. I don't see people perceiving the immediacy of that challenge.

You've been in this job seven years now, after having never previously worked in education. What is the No. 1 thing you've learned about improving public education?

It's to improve the teachers and to have a teaching force that can really take your kids to an entirely different level. That's been the focus of so much that we've done in New York -- raising salaries, alternative certification, bringing people into the teaching profession from entirely different pathways, differentiating pay. We're still in the early innings. There are a lot of other things that have to go with that, but if you focus on effective teaching, that's the game changer.

You mention differentiating pay -- rewarding teachers who achieve better results. In the business world that's obvious, but it's not the way things have traditionally been done in public education. How hard was it to make that happen?

Public education is an entirely different culture. Fundamentally, the only differentiator is seniority. The power in the system is fundamentally the power of the bureaucracy, of the political forces, of the union.

When I was at Bertelsmann, we were constantly focused on how to incentivize the workforce, inject increasing accountability, deciding where to substitute technology for human capital.

In a public school system it's an entirely different set of questions. And until you get used to the questions, you can't think too well about how you want to answer them.

But one could argue that public school teachers, especially the best ones, aren't in it for the money in the first place. Does paying them for performance really work?

I think it does. We haven't seen enough of it in America to know. But think about it this way: Every university I know pays differently for science teachers than it does for English teachers. But I pay the exact same for a science teacher and a physical education teacher. And then I pay the same whether you work in my highest-need school or in my most successful school.

Look, money isn't the only thing that drives teachers -- indeed, it isn't the only thing that drives school chancellors -- but money is an ingredient in the mix of things that matter to people. Fairly compensating them if they take on the tougher assignments, if they're doing the work where it's harder to attract people, like science and math -- that seems to me a critical component.

Another big change you made was bringing in figures from the corporate world, such as Jack Welch and others, to help train school principals in leadership. Why did you do that?

From the beginning we said there's no such thing as a great school system; there are only systems comprising great schools. The unit that matters is the school, and no unit is going to succeed without great leadership. That's an important concept.

In education the principal is the weakest link in the chain. Bureaucracy has a lot of power; politics has control of money; the teachers have power because they have a very strong union. But the principals are in a union with the assistant principals, and there are more assistant principals than principals.

So the leader, in a weird way, is the weakest link. We really started to focus on leadership training, and we have a program now that was built on the Crotonville model [from General Electric] where we have boot camp for principals and aspiring principals over the summer, and then they mentor and intern with one of our more successful principals. It is amazing to me that the same school with two different principals can get entirely -- entirely -- different outcomes.

Jack [Welch] did something that was great: He challenged all my senior leaders. We had a retreat, and he said, "You guys keep talking about 'instructional leaders.' That's because you're uncomfortable talking about leadership. In the phrase 'instructional leader,' the more important word is 'leader.'"

Don't you have to change the system for any of this to work?

If you want great leadership, you've got to empower your leaders. When I started, superintendents used to pick the principals and then pick the assistant principals. I said, "If the principal can't put together his management team, it's not going to work." And they said, "Well, Chancellor, you shouldn't do that because our principals can't pick assistant principals." I said, "If they can't pick assistant principals, we've got to get new principals."

Isn't that ridiculous? Shouldn't principals be deciding which administrators they need, which guidance counselors they need, what community programs they want to bring in, whether they want to have extended day, extended week, extended year, and start to differentiate based on their challenges and also maybe take some risks in this game?

To what extent are they allowed to do those things today?

Much, much more now. Principals in New York City have significantly greater discretion on issues like extending the day, having Saturday programs, hiring a teacher, hiring another assistant principal.

By the same token, there's far more accountability, and that's a big change. I think people would be surprised by this: Every principal in New York City signs an agreement saying what their prerogatives are, what discretion they have, and also what their accountabilities are. And if they don't meet their accountabilities, we can terminate them or close their schools. We do that. And that's a very different way of doing business.

Most people who came to public education think that if you show up on day one and just stay out of trouble, you can be there forever. We're trying to develop a performance-based, accountability-driven culture, and we've had quite a bit of success with our principals.

No one will be surprised that you've had some conflicts with the teachers union. Bottom line, are teachers unions friends or foes of improving public education?

I think it's more nuanced than that. It's like the old song about "that's the glory of love." You know, "You've got to give a little, take a little, let your poor heart break a little. That's the story of, that's the glory of love." It's also the story of and glory of union management negotiations in public education.

The unions' job is to protect the workforce. That's a legitimate and appropriate role. As we move away from what I view as an arbitrary, politically driven system to an accountability-based system, then when teachers don't perform well, we have to figure out ways to move them out of the system.

It doesn't surprise me that unions aren't at the forefront of the movement to end or change tenure or to move off a seniority-based system. But I think there's a dialectical process. With the President out front on this, talking about pay for performance and teacher accountability, I think that will change the discussion.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has made public education one of its priorities and has given your department money to try some experiments -- even though when you were U.S. antitrust chief, you sued Microsoft. What have you learned from those experiments?

The Gates Foundation has given us [a total of] $150 million, and a principal said to me very wisely, "Think what the Gates Foundation would have given you if you hadn't sued Microsoft." But $150 million is not a bad number.

They gave us about $110 million to redesign large, failing high schools. We had 30 to 50 that had graduation rates of only 25% to 28%. They had around 3,000 kids each.

We have closed those and replaced them, bringing in partner organizations like Outward Bound, the Asia Society, or New Visions, and instead of having one school with 3,000 kids, we now have six schools with 500 kids. So you have much more personalization.

Politically this was an enormous challenge, so it was great that we didn't have to use public monies to do the retooling.

How are those experiments working?

You'd expect that some of them are working very well, some working okay. Overall, the graduation rate in the smaller schools with the same students is significantly higher, but not every small school has worked well.

You've had more definite results in your experiments with charter schools?

When we started, we had 16 or 17 charter schools. When we opened school this fall, we were one short of 100. So we really got that going, and that has brought some competition.

This is a word you've got to whisper in education, but competition is a good idea that has helped us some. The leadership thing has helped us. Some of the pay things -- still too early to tell. But we're getting good progress. We've got a long way to go. But for the decade before we got here, the city graduation rate was about 46%. It's now over 60%. Is that anything to go home and shout about? No, but it's real progress.

When you look at your own story, what was most important in your achieving what you did?

I really believe it's education. My parents taught me early that in the absence of education, I could end up living in the same public housing that I was living in as a child. My father never made it out of high school. Nobody in my family had ever been to college. This was an important message. I didn't like living where I lived when I was a kid.

But it was teachers, time and again, who would challenge me. My high school physics teacher, Sidney Harris, basically convinced me that I could go to Columbia College -- that I could get in. He got me a National Science Foundation fellowship my junior year in high school. I'd never been out of my parents' world.

It made me realize that, first, I can actually run in this race, I can play in this game. And second, I met people who then inspired me. It was my teachers who kept saying, "Don't let your background, your family situation, define your world." And I believe it deeply -- that's the transformative power of education. ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More