Search News

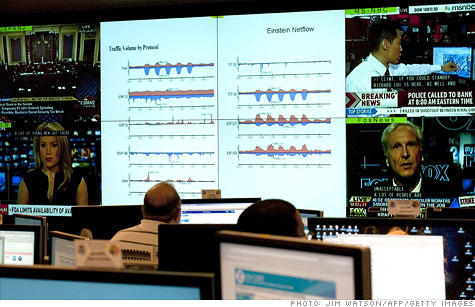

Analysts at the National Cybersecurity & Communications Integration Center keep tabs on America's digital infrastructure.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- Cybercrime isn't just a threat to your bank account or personal computer -- it's an issue of national security.

Foreign spies and organized criminals are inside of virtually every U.S. company's network. The government's top cybersecurity advisors widely agree that cyber criminals or terrorists have the capability to take down the country's critical financial, energy or communications infrastructure.

"The reality is that our infrastructure is being colonized," said Tom Kellerman, former commissioner of President Obama's cyber security council, at a Bloomberg cybersecurity conference held in New York last week. "The terrifying thing is that governments no longer have a monopoly on this capability. There is code out there that puts it in anyone's hands."

Using cyberspace to take over our infrastructure, turn off our electricity or release toxins would amount to "a digital Pearl Harbor," Richard Clarke, the coordinator of President George W. Bush's counterterrorism initiative, famously said in 2009.

Staving off such an event is a logistical nightmare.

Much of America's critical infrastructure is owned by businesses. Gaining intelligence on cyber threats -- both in advance and after an attack has been launched -- requires cooperation from companies and, often, from private individuals.

That's why Congress is taking up as many as six different bills this week that deal with that issue: balancing the security of our core infrastructure with the privacy of corporations and people.

There are some key differences between the bills, and lawmakers are furiously trying to merge them together.

The bill most policy analysts focus on as the likeliest to pass is the Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act, introduced by Representative Mike Rogers, chairman of the House Intelligence Committee. It passed his committee with strong bipartisan support (a 17-1 vote) in December, and it has more than 100 co-sponsors on both sides of the aisle.

At the bill's core are incentives for private businesses that control core, critical infrastructure, particularly in the finance and energy sectors. Those businesses would receive tax breaks if they share information with one another and the government about attacks. There are rules that would force them to strip out any non-crucial information from customers or business partners.

A rival Senate bill, sponsored by Sen. Joseph Lieberman, would instead mandate information sharing through government regulation. That bill is supported by President Obama, but most speakers at the conference thought it had little chance of passing.

Critics have attacked the bills both for being too lenient on privacy and for being too rigorous. The bills have been blasted by both civil liberties organizations, and, interestingly, those in the intelligence community.

"All the bills on the Hill are insufficient," said Mike McConnell, formerly President Bush's national intelligence director. "We say we don't want to infringe on privacy rights or burden industry in any way, so the result is we don't do anything."

At a corporate security conference last month, FBI Director Robert Mueller warned attendees: "There are only two types of companies: those that have been hacked, and those that will be."

McConnell thinks it will take a "catastrophic event" to force changes.

"We are incredibly vulnerable," he said. "If we don't make our policy makers think about this seriously, we'll be dealing with something like 9/11."

Other nations and organized crime organizations have more and better intelligence on U.S. citizens and businesses than the U.S. government itself does, in McConnell's view. That's a major policy dilemma.

Privacy advocates like the American Civil Liberties Union counter that the Rogers bill would kick off a free-for-all in sharing of customer records.

The bill would "create a cybersecurity exception to all privacy laws and allow companies to share the private and personal data they hold on their American customers with the government," the ACLU wrote in a December letter to Rogers and others in Congress.

It added: "We will vigorously oppose this legislation as inconsistent with the long tradition of Americans' reasonable expectations of privacy."

Yet other security professionals stressed that we have to rethink privacy in a world where hackers have already infiltrated all our systems and know everything about us.

"Let's get real," said Kellerman. "We have 100,000 Big Brothers. Meanwhile, the United States is fighting this with one hand behind its back."

"We have been juvenile about the discussion of privacy," said Roger Cressey, senior vice president at security consultancy Booz Allen Hamilton. "This is an issue of leadership. If we don't take it seriously, we're going to have a serious attack."

"We have to change our perspective on what's permissible and not permissible," said Col. Cedric Leighton, a former military intelligence officer with the U.S. Air Force. "It's not a lost cause, but only if we know what we're facing."

The bills aren't perfect, but even opponents of the Rogers bill said something needs to be done.

"We don't all have to agree on everything to do something," said Howard Schmidt, President Obama's current cybersecurity coordinator. "We talk about it and talk about and talk about it, and all we're doing is just admiring the problem. We need the authority to do the things we've been talking about for quite a while." ![]()