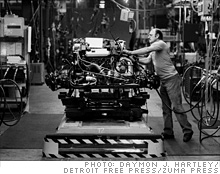

A GM factory gets a second chance

When GM opened a plant in Detroit 23 years ago, the hope was that it would revitalize the city. It didn't. Now the facility will build the plug-in hybrid Volt. Will this time be different?

|

| THEN: GM's Detroit-Hamtramck factory opened in 1986. |

|

| NOW: Det-Ham now builds the Buick Lucerne and will produce the Chevy Volt next year. |

|

| George McGregor, president of Det-Ham's union, UAW Local 22 |

DETROIT (Fortune) -- Here's George McGregor, autoworker. He's 63 years old, a gregarious, barrel-chested graybeard with a gold stud in his ear and a gold cross around his neck.

This is his story. It's a particular story, all his own. It's also an American story, specifically, a Detroit story, about a time that has passed and a city that will never be the same. And it's a story about a factory -- GM's Detroit-Hamtramck assembly plant -- one of only two factories still making cars in the city where carmaking was born.

GM first pitched the idea for a new Cadillac assembly plant on land straddling the line between Detroit and the municipality of Hamtramck almost 30 years ago, during a time of crisis in the auto industry. American carmakers, under attack from Japanese imports, needed to cut costs, and GM believed that a new factory with robots and other cutting-edge technology was just the answer.

To Coleman Young, Detroit's mayor at the time, the new plant was a godsend. Mayor Young believed so strongly in the project that he agreed to level an entire neighborhood known as Poletown -- 465 acres of homes, businesses, and churches -- to make room for it. An epic showdown ensued. The mayor prevailed. Poletown was obliterated, and the facility was built. The experiment didn't work out as hoped. Over the years demand for GM's cars waned, and the original 6,000 workers at the plant shrank to 4,000, then 3,000, and ultimately fewer still.

Today the U.S. automobile industry is again in crisis, and GM, in an eerie repeat of the past, is betting that technology is the answer. This is the factory where, late next year, GM plans to begin building the Volt, Chevy's $40,000 plug-in electric car.

The stakes have never been higher: for GM, which recently emerged from Chapter 11; for taxpayers, who wrote GM checks totaling more than $50 billion and now own 60% of the company's depressed assets; for the American auto industry, as it struggles to reinvent itself in the twilight of the internal combustion age; and not least for the city of Detroit, still betting, however improbably, on a Motor City renaissance.

"Detroit has been and always will be the home and epicenter of auto innovation," argues Mayor Dave Bing, a former NBA star with the Pistons. He sees his city as the logical place for the next generation of battery-powered cars to be engineered, designed, and built; it's an exciting opportunity to spur job and economic growth. And he will have help implementing this vision.

Earlier this year Gov. Jennifer Granholm and the state legislature, despite crushing fiscal woes, approved $945 million in tax credits and grants to encourage the development of alternative vehicles in Michigan. In August, Vice President Joe Biden came to Detroit to distribute to the state $1.35 billion in DOE grants, courtesy of the American Recovery and Investment Act.

But will it be enough and in time, or will Detroit once again fall short of its dreams?

Few hope for the success of the Volt and a bright future for Detroit more than McGregor. He came here 41 years ago, a Southerner with a high school education, searching for a better life. He was there at Det-Ham the day it opened in 1986. Today he's president of the plant's union, United Auto Workers Local 22. "I will do anything I can to keep my people working," McGregor says with a grim conviction that belies his private doubts. "As many as I can."

When McGregor was a teenager, he worked in a factory in Memphis, making handles for hoes and axes and earning minimum wage. "We sent handles all over the world," he says. "Dollar and a quarter an hour. Got my paycheck, $46, had to give my momma $20 of that, so that made me have $26 left."

He might be working there still if he hadn't been drafted. One night in the barracks at Fort Campbell in Kentucky, while everybody was sitting around shining shoes, the talk turned to jobs left behind. "There was this guy that worked for Chrysler," McGregor says. "He brought out his check stub. I looked at his check stub. I said, 'I'm going to Detroit when I get out of the Army.' I got out of the Army in '68 -- January the 20th, 1968. February the 7th, I hired in at Fleetwood Fisher body."

McGregor was almost too late. He arrived six months after the '67 riots, and long after Detroit's population had peaked in the 1950s at around 2 million and the city had begun emptying out.

Today barely 900,000 inhabitants remain, spread thinly across 138 square miles, about a quarter of which, incredibly, are not just uninhabited, they're utterly empty. No people, no structures -- just tall grass bending in the summer breeze, mixed with nodding blue cornflowers and Queen Anne's lace.

But Detroit in the late '60s was still the bustling hub of the automobile universe. General Motors was still the biggest, most profitable corporation in America. Hudson's colossal redbrick department store on Woodward Avenue still towered over a vibrant downtown shopping district. "The city was beautiful," McGregor remembers. "It was alive!"

McGregor built bodies for Cadillac in a six-story factory on Fort Street in the West End. Two miles north, at the corner of Michigan and Clark, was an even larger factory that received the bodies and married them to chassis. Together those two factories employed 18,000 dues-paying, health-insured, pension-accumulating members of the UAW, many of whom didn't just build Cadillacs, they bought them for themselves.

McGregor has in his East End garage a 1977 Cadillac DeVille d'Elegance with a 425-cubic-inch V-8 and an eight-track tape player. His current ride is a Cadillac CTS (it's a little cramped for his taste), but he'll never sell the DeVille. It's a relic of a bygone era whose demise began with the coming of the oil crisis in 1973 and the subsequent invasion of the Japanese imports.

Throughout the 1970s, as Japanese automakers steadily gained market share, Washington threatened to impose tariffs. Japan responded by shifting production to North America, starting with Honda's Marysville, Ohio, plant, which opened in 1982.

By 1990 every major Japanese carmaker had at least one "transplant" in the U.S. Because the transplants were heavily automated, typically non-union, and often located south of the Mason-Dixon line, they only accelerated Detroit's decline.

Det-Ham was supposed to reverse that alarming trend. It would be ultramodern in every way, an efficient, single-level facility stuffed with the latest technology, and it would be in Detroit.

The last time anyone had built a new car factory in Detroit was in the 1950s. The city establishment went gaga, and instantly the fate of Poletown's 4,200 blue-collar Polish- and African-American residents was sealed.

"They were lining up against these major forces," says documentary filmmaker George Corsetti, who chronicled their struggle. "You had the archdiocese, who wanted to dump these churches. [It quickly sold two, St. John's and Immaculate Conception, to the city for $2.39 million.] You had General Motors, of course, that at the time was one of the biggest corporations in the world. You had the city of Detroit, which was desperate. And the UAW. The residents weren't going to win this fight, and I knew that from the beginning."

They did fight, though. There were marches, demonstrations (joined by lefties as well as libertarians), and on the summer morning that the wrecking ball arrived to demolish Immaculate Conception, a final, heroic occupation that resulted in 12 arrests.

Throughout, Mayor Young professed bafflement at why anyone would oppose what he viewed, gratefully, as a gift to his beleaguered city. On the day in January 1982 that the new plant's first structural column was lifted into place, Young, looking on with GM chairman Roger Smith, told the Detroit Free Press that GM had been the victim of a "vicious and unreasonable assault." "I don't know," Young said. "It's like shooting Santa Claus."

McGregor agreed with Young. He viewed the new factory as a blessing -- a modern, spacious, air-conditioned facility with "a place for everything and everything in its place." Standing on the roof on a clear day, he could see the old GM headquarters building on West Grand Boulevard. "We all felt good about it because it was an ideal place to work," McGregor says. "Everybody was proud of it."

Of course it was heartbreaking for the many people who would lose their jobs. McGregor remembers walking through the plant in the days after it opened, listening to co-workers complain, "Oh, man, that's my job, and the robot's doing it!"

(There were problems with the robots from the outset -- serious accidents, not all of them easily explained. That led some workers to cast a wary eye on an old cemetery, hidden behind high walls on the northern edge of the property -- it's all that's left of Poletown -- and conclude that the plant was cursed. "We always had problems," McGregor says. "Lights would go off, couldn't get nothing to work. Like an omen or something.")

But McGregor above all was a realist. "I knew there was no way in the world General Motors could survive building cars in a factory six stories high, then shipping them down the highway so they could be completed," he says. "No way."

So McGregor made his peace with progress; with the closing of two obsolete factories and the elimination of 18,000 jobs in exchange for the promise of 6,000 supposedly rock-solid jobs at Det-Ham. It turned out to be a bad bargain. Over the next quarter-century GM's sales faltered, and the factory shed all but 1,300 jobs.

It's 2009 now, a hot and windy Thursday in August. Det-Ham's vast parking lot is mostly empty. The plant is slowly gearing up to resume production after an extended two-month summer layoff. "We'll start to be in full rock-and-roll position early next week," says plant manager Teri Quigley, who greets me in the lobby.

Quigley's dad was a PR man for GM in the days of Roger Smith. Of the 14 assembly plants GM operates in the U.S., only two are run by women. Quigley is one of them. She's vibrant and disarmingly petite ("five-two on a good day"), a self-described "manufacturing rat all my life" with long brown hair that's pulled back into a bun for safety as we head for the plant floor.

Rock and roll, Quigley explains, is not what it used to be. Production of Det-Ham's current line -- the Cadillac DTS and the Buick Lucerne, two closely related luxury sedans -- is at a fraction of capacity. The hope for growth lies with the Volt.

If you want to see one today, you need to drive 10 miles north of Det-Ham to GM's Tech Center in Warren, Mich. There, vehicle line director Tony Posawatz ("Sounds like kilowatts -- I was born to do this program!") shows off a third-generation test Volt, the version where "everything comes together."

Outwardly it's a conventional compact sedan, with space, barely, for five, and a body that's unlikely to turn heads on the highway. The instrument panel is pretty cool -- vaguely suggestive of an iPod.

Otherwise the justification for the $40,000 price tag for a Chevy is hidden: Under the back seat, where the 400-pound cross-shaped lithium-ion battery resides and under the hood, where there's a 1.4-liter gasoline engine whose sole purpose is to recharge the battery, extending the Volt's 40-mile range to more than 300 miles.

Back at Det-Ham, Quigley is on schedule to begin limited production of the Volt as early as next March. Workers will get some special safety training so they don't electrocute themselves, says Quigley, but otherwise the Volt is an assembly job like any other, requiring no special processes and no additional staff.

She is looking forward to when "the spotlight comes on" in November 2010, and road-ready Volts start rolling off the line. Rolling slowly. GM isn't talking exact numbers, but Quigley says the initial output will be "low." That means no more than a few thousand units in the first year. She adds, "As we prove out the technology and the market demand comes, we can run this plant to full capacity."

Whatever benefit Detroit gets from the Volt, if any, won't be felt for years. Even if Volt sales climb into the tens of thousands, Det-Ham could handle that annual volume with only one shift. That would hardly put a dent in an unemployment rate in Detroit that, at 17%, is nearly twice the national average.

And where would those workers come from? Probably not Detroit. More than 70% of Det-Ham's current workforce lives outside the city. GM is also investing $43 million in a renovated facility in southeastern Wayne County, where it plans to build the Volt's battery packs. (Assemble them, that is. The battery cells themselves will be manufactured in Troy, Mich., by Compact Power, a subsidiary of Korea's LG Chem.) All that may help Michigan but not Detroit.

Even so, Quigley has no illusions about what's at stake here. GM, remember, is a ward of the U.S. Treasury. Its CEO is a government appointee. Its track record in green tech is spotty at best, even when compared with its laggard U.S. competitors.

Now it's proposing to leapfrog its rivals with a hastily developed, expensive technology, knowing it needs nothing less than a grand slam if it's going to regain the confidence of investors, begin paying back the taxpayers, and jump-start the green-car economy that may well be Detroit's last hope.

How important, then, is the Volt? Quigley doesn't hesitate: "How much more important could it possibly be?"

Right. And honestly, who in his right mind isn't rooting for GM to pull this off? At the same time, who in his heart really believes that it can? Does McGregor even think so?

"It's like this," he says carefully. "A drowning man will grab anything. That's what we do. Guys are losing their jobs, their 401(k)s. So they throw us the green jobs and the small electric car, and guess what?" He's laughing now. "Here we go!" Or not. ![]()