Making Detroit a tech hub - One mogul's vision

Online-mortgage mogul Dan Gilbert wants to spark a revival by moving his headquarters and 1,700 workers to the heart of the city.

|

| Dan Gilbert, founder and chairman of Quicken Loans |

|

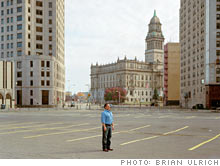

| Gilbert stands in deserted downtown Detroit on a weekend. Workdays aren't much busier. |

(Fortune magazine) -- It is noon in downtown Detroit, a glorious autumn day in the nexus of the city's business district. A large crowd of people stride up the street toward a sleek, glass-walled tower in the Campus Martius complex.

Steps away, office workers lounge at café tables in a plaza, eating and chatting beside a fountain and a Civil War-era statue. A row of historic storefronts beckons shoppers. On the roof of the Lafayette Building at the corner, two trees stand, as if in a garden, their leaves a seasonal gold.

Only as you draw close do you see that the milling crowd belongs to a movie production: a studio remake of "Red Dawn," lured here by generous incentives from the state of Michigan. Most of the renovated Merchants Row storefronts have yet to find tenants. The rooftop trees, growing wild 14 stories up, are real but doomed, as demolition crews gouge out chunks of the crumbling building, proceeding with a teardown.

This is Detroit 2009, where announcements of a renaissance can be as illusory as an army of movie extras. Despite billions in public and private investment over the past 15 years -- including two new stadiums, a river walk, three new casinos, thousands of new hotel rooms and loft and apartment units -- downtown Detroit may be the quietest major city in America.

The GM Renaissance Center is emptying out; the 47-story Penobscot Building, once a throbbing hub, is in receivership; and the stately Comerica building is only a branch office since the banking company moved its headquarters to Dallas in 2007 after 158 years in Detroit. A Detroit News report recently identified 48 empty buildings downtown of 10,000 square feet or more.

This year the remaining semblance of a local economy was battered to a surreal degree. The Detroit school system went into receivership, the unemployment rate hit 28.9% in the city, and two of the Detroit Three automakers filed for bankruptcy. Could the climate get any worse for doing business here?

"Pick any point in time -- it's about as bad as you can get right now. There's no new tenant activity," says Cameron McCausland, director of brokerage service for Colliers International, based in the city's suburbs.

Even the R-word seems hexed. Renaissance Detroit, a civic group of business leaders, has abandoned the urban theme, renaming itself Business Leaders for Michigan.

Part of Detroit business tradition, however, almost as much as the epic decline, is the periodic emergence of a square-jawed, impatient entrepreneur who believes he can spark a turnaround by force of will.

The newest is Dan Gilbert, 47, founder and chairman of the online mortgage company Quicken Loans, who announced in July his decision to uproot 1,700 employees from a low-slung headquarters in suburban Livonia and plant them next summer in the glass-walled tower at One Campus Martius, in the barely thumping heart of the city. (See editor note at bottom.)They'll occupy four floors of the Compuware headquarters building, where they'll share use of a preschool, fitness center, and cafeteria.

Gilbert has made a concerted effort to get his suburban employees enthused about the move, including field trips to the city, where some workers toured lofts and apartments.

"The reality is better than I thought," says Kristin Broadley, 35, a Quicken Loans manager who plans to move downtown rather than commute. "The possibility of living in an urban area is quite exciting."

The $400 million Compuware tower, opened in 2003, is the legacy of another pioneer, Peter Karmanos, 66, the founder and CEO of the business-software maker. It was Karmanos who first persuaded Gilbert to seriously consider moving, and whose conviction rubbed off on him. "I have to believe that, objectively, it's the right thing to do," says Gilbert.

He knows that his march into Detroit won't be a success unless people follow, not just for sentimental or quixotic reasons, but because it makes good business sense. Right now a primary selling point is cheap rents: office space at $18 a square foot, vs. $32 in downtown Chicago, often with the first year free on a five-year lease.

"It's the opportunity to get in low and sell high," says Gilbert. "It's an untapped market from an intellectual standpoint, and from a physical standpoint there are great buildings. The idea is to get to the tipping point where companies start believing that they can't afford not to be in Detroit."

His intention is to recruit a flock of innovative, edgy companies into the Campus Martius area. The fact that Gilbert and Karmanos are onto the same notion has created energy, a whiff of hope. "When they move, you start thinking, 'What do they know that I don't know?' " says Rich Homberg, president of Detroit Public Television. The station, which relocated to exurban Wixom, now plans to open a new studio in Detroit.

For self-made Detroit moguls, there are two important steps toward becoming a local legend. One is owning a sports team, even if it's not necessarily local. Gilbert owns the NBA's Cleveland Cavaliers, and Karmanos, the NHL's Carolina Hurricanes. Mike and Marian Ilitch, the founders of Little Caesar's pizza, own the Tigers and the Red Wings.

The other step is committing resources to downtown revitalization, a sign of civic gravitas and even machismo: It's not for the faint of heart.

"I think there's a mindset that there's civic responsibility to do it," says Peter Cummings, a real estate developer who served as chairman of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. What makes it an Olympian task, he says, is the cycle of "encouraging signs followed by further deterioration and disappointment. You have to have a passion for it, because you can get a better return on your time and your financial capital elsewhere."

Ever since Henry Ford II staked out the territory, leading Ford Motor Co. (F, Fortune 500) to build the Renaissance Center on Detroit River frontage in the 1970s, Detroit's challenge has exhausted and disappointed investors. In October 2008, Cleveland-based developer John Ferchill triumphantly reopened the historic, 455-room Westin Book Cadillac Detroit hotel after a $200 million renovation, just in time for the financial crisis.

"I like to say that the country shut down when the hotel opened," says Ferchill, who welcomes the Quicken Loan arrival as critical to the downtown's survival. "I really believe it's as significant a move as anything you could possibly do."

It's also characteristic of Gilbert, a driven, charismatic personality who won notoriety at Michigan State for his part in an illegal sports betting ring, for which he paid a fine and did community service. He became a legit entrepreneur when he joined with his younger brother Gary and a friend, Lindsay Gross, to start Rock Financial in 1985 with just $5,000.

"We were 23, and we barely knew what a mortgage was," says Gross. Dan was the driving innovator. "He'd say, 'Why are we going through a middleman, the realtors, to get to the customer? Why not get to the clients first?'"

So the company started 1-800 call centers to expand nationally and later converted them to web centers in 1998. Voilà! A sizzling tech company was born. Seeking to expand its Quicken brand of software, Intuit (INTU) bought Rock Financial in 1999, renaming it Quicken Loans, for $532 million in stock. The marriage ended in 2002 when Gilbert and an investor group bought back the company for $64 million, retaining the Quicken name.

When Gilbert hatched his plan to move downtown two years ago, it was an even grander scheme. "This is more than a project for me. It's a movement," Gilbert said at the time, unveiling plans to build his own office tower. He was then eyeing the longprepped site that last housed Detroit's premier department store, Hudson's.

Shortly thereafter the mortgage meltdown kicked in, rattling Quicken's bottom line. The company laid off 250 employees in 2008 but adjusted, picking up market share as other mortgage lenders disappeared.

The company is known for its hypercompetitive culture. While it ranked this year as one of Fortune's 100 Best Companies to Work For, it is fighting two class-action lawsuits by hundreds of former employees who claim they were denied overtime pay. The company contends their jobs didn't qualify for it.

Gilbert's vision for Detroit is to reweave the social fabric of business. He wants to attract a hub of tech companies, a cluster of creative minds. It will start with just one building: Compuware's 2,300 workers and Quicken's 1,700 will fill the tower at One Campus Martius almost to capacity. "My point is that if you go to Silicon Valley or Boston or Chicago, people are close together, eating and bumping into each other, drinking coffee, and literally creating value," Gilbert says.

Detroit's 139 square miles, and its endless suburbs, pose a geographical obstacle to human connection. That's what needs to be reversed. Gilbert sees young employees -- the average Quicken worker is 30 -- eager to live in urban areas.

Without a viable downtown, companies like his won't be able to attract smart, educated people. "We're going to bring more companies. That's my goal. I want people to ultimately think Detroit is a great investment, that young people want to be there, living, playing, and working."

The job of linking up a disconnected city has been assigned to Matthew Cullen, the president of Rock Ventures, a company that coordinates Gilbert's holdings. Gilbert hired Cullen from GM, where the executive engineered the automaker's 1996 purchase of and move to the Renaissance Center.

Among Cullen's projects is M1 Rail, a private light-rail project that would bridge the currently forbidding three-mile stretch between Detroit's downtown hub and the midtown area anchored by Wayne State University and the city's first-class Detroit Institute of Arts.

Gilbert acknowledges the long stall in Detroit's revival but blames poor execution. He cites the RenCen, whose towering mass looms at the eastern edge of downtown, both isolated and daunting for visitors to navigate.

Even the city's riverfront was underused and wasted until it was officially reclaimed and opened in 2008 as a walkable, landscaped, three-mile-long park. "You can't just do it 95% right," Gilbert says of previous turnaround projects. "It has to be 100%."

Gilbert has a willingness to play hardball -- and a disdain for inaction and bureaucracy that's a rebuff to Detroit's old automotive corporate culture. You could argue that GM's bankruptcy, and other Detroit disasters, punctured the city's defensive resistance to change.

Dave Bing, the NBA Hall of Famer who is now Detroit's mayor, is challenging once-sacrosanct union rules and benefits. The city's urban-farming advocates include John Hantz, a financial services entrepreneur seeking to rezone vast acreage for commercial crops.

Dan Gilbert, for his part, has always had visions of doing big things. In his dreams for Detroit, he just needs a little more company.

Laura Berman is a columnist on local and national affairs for the Detroit News.

-- An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to Dan Gilbert as CEO of Quicken Loans. He is founder and chairman. A corrected version is above. ![]()