Search News

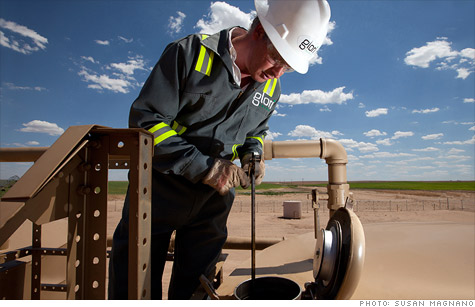

Glori Energy says it can get 30% more crude out of a well by growing bacteria on the oil. Here, a Glori employee performs tests at a well in Kansas.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- In the days of rising oil prices and fears of dwindling supplies, it makes sense to get as much crude as possible out of any given well.

After a well is drilled its natural pressure gradually subsides, eventually making it too costly to pump out the remaining crude. Although a well may seem dry, up to two-thirds of its oil remains underground.

Enter Glori Energy and the bacteria.

Using technology originally developed in India, Houston-based Glori is using a novel system to stimulate the growth of bacteria in an oil well. As the bacteria grow on the droplets of oil, it becomes slicker and allows it to flow more easily.

"Our strategy is to go from brute force to biology," said Glori chief executive Stuart Page.

Reviving old wells: Glori's technology is aimed at older wells where the natural pressure has decreased to a point where the oil no longer flows to the surface by itself. Of the 5 million or so barrels of crude oil produced in the United States each day, about half come from such wells, said Page.

Glori isn't the only one operating in this space, there are a number of companies and technologies intended to keep production going once the natural pressure subsides. Injecting water, carbon dioxide and natural gas are all common ways to maintain pressure in the well.

Glori's technology works with wells that use water to maintain the pressure and force the oil to the surface.

The company will take a sample of the particular bacteria present in a well, then develop proprietary nutrients at its lab that it believes will encourage more bacteria to grow in the water there. It then injects those nutrients down a well, in addition to taking measures to clean the water and develop a circulation pattern that enables the bacteria to grow.

Page said the impact on the water quality in the well -- which is not drinking water -- is minimal. In fact, he said the water often comes back cleaner then before the process was begun.

In addition to growing on the oil droplets themselves and making them more viscous, Page said the bacteria also change the size of the droplets and brings more oil to the surface.

Page estimates the technology can make old oil wells about 30% more productive.

"There's billions of barrels of oil available without drilling a single well," he said.

From the four corners of the world: The company is truly the product of the globalization era, a marriage of firms from four continents.

The technology was developed by the Indian National Oil Company back in the early 1990s. In 2005 a New York-based private equity firm founded Glori. They quickly advanced the technology through the purchase of an Argentinean biotech outfit and oilfield expertise gained through a partnership with Norway's Statoil.

The company has caught the attention of some influential people within industry.

Earlier this year Glori was one of a handful of companies chosen to present on an "innovators" panel at IHS Cambridge Energy Research Associates' annual energy conference in Houston, the largest oil conference in the United States.

And the company recently received an undisclosed investment from a venture capital fund controlled by General Electric (GE, Fortune 500), utility NRG (NRG, Fortune 500), and ConocoPhillips (COP, Fortune 500).

Still, the challenges for an upstart firm operating in a field of giants are many.

Chief among them is getting getting oil companies to invest additional money in projects than have already cost them millions, if not billions, of dollars.

Due to the high costs associated with developing an oil well, big oil firms are not known to be fast movers when it comes to adopting new technology, said Neal Dingmann, managing director of equity research at SunTrust Robinson Humphrey in Houston.

Plus, many of the big oil companies, as well as big oil service firms Halliburton (HAL, Fortune 500) and Schlumberger (SLB), are developing similar technologies in-house.

"You're taking the big boys on directly," said Dingmann.

To succeed, he said a company like Glori needs to get one big-name oil company to adopt the technology, then the others will see that it really works.

Page said the company, which is still privately owned, is working on doing just that.

He said said Glori in talks with a half dozen oil companies currently, and plans to announce its first commercial partnership next week with a smaller U.S. oil company.

But he said a deal with big oil firm could be on the horizon. ![]()