Search News

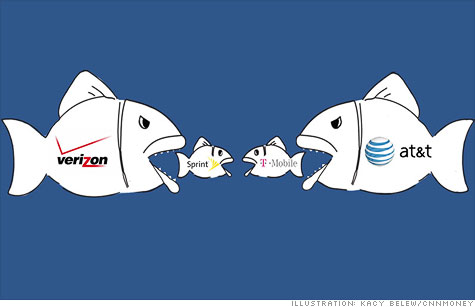

Big wireless carriers are all hunting for spectrum -- which often means buying out their rivals.

This is part two of a week-long series on the cell phone capacity crunch.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- As airwaves become scarce, the spectrum crunch is turning a field of "haves" and "have-nots" into a sharply divided set of winners and losers.

Those carriers with the biggest batches of high-quality spectrum have more bandwidth to satisfy customers' growing demands for mobile phone calls, texts and Internet usage. That means fewer dropped calls and faster download speeds.

Those that don't? Picture a repeat of what happened to AT&T shortly after the iPhone 3G debuted. The data overload crippled the network, leading to spotty reception and slow speeds in some regions.

"Wireless operators have to decide whether they spend money acquiring new spectrum or building tens of thousands of new cell sites all over the country," says Dan Hays, a partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers' consultancy. "That's the big dilemma."

Both of those options cost billions. There's a third choice: consolidate. By merging, carriers can gain access to both spectrum and more cell sites.

That can also cost billions, but it's a turn-key solution.

"You get economies of scale, and that buying power advances the kind of network you can have," says Akshay Sharma, analyst at Gartner.

There's just one glaring problem with that scenario: Regulators hate it.

AT&T's failed $39 billion bid for T-Mobile was largely aimed at getting its rival's spectrum. The Department of Justice and the Federal Communications Commission killed the deal, saying it would be too damaging to wireless competition.

That put the entire industry on notice: The carriers will have to solve their problems without any blockbuster takeovers.

The regulators' main concern was that the deal would take the ranks of national carriers down from four to three. That's why experts now expect the big players to focus instead on acquiring smaller, low-cost carriers like MetroPCS (PCS) and Leap Wireless (LEAP). Their spectrum could relieve capacity issues in large metro areas, which are the places most crippled by the crunch.

Industry analysts also think that Sprint and T-Mobile could gain approval to merge, though that's a bit like two drowning victims clinging together. Sprint is losing piles of money every quarter, while T-Mobile is hemorrhaging customers with contracts.

Another possibility is that several carriers could partner in a spectrum-sharing joint venture.

But the most likely scenario is that the carriers continue fighting each other to snap up the last remaining large swaths of high-quality spectrum.

Last year, AT&T bought a sizable chunk from Qualcomm (QCOM, Fortune 500), which the chip company had used for its failed Flo TV venture. Verizon recently agreed to pay $3.6 billion to buy spectrum from a consortium of cable companies.

That means there are only two commercial holders left of big spectrum chunks: The Dish Network (DISH, Fortune 500) and LightSquared.

LightSquared, a venture-backed company that wants to build its own nationwide wireless network, has vast ambitions and an equally gigantic problem. Its spectrum is only licensed for satellite services, not the terrestrial transmissions needed to carry wireless phone signals. LightSquared is currently caught in -- and losing -- a high-stakes regulatory fight over the issue.

That leaves Dish. The company has considered building its own wireless network, perhaps by snapping up Sprint or Clearwire, but the costs of doing that are scary. Some analysts think Dish will take the plunge, while others predict that it will go the safe route and sell off its holdings.

Either way, it's got vultures circling.

"If a competitor doesn't make it, you can assume that AT&T or Verizon would munch up that competitor," says Rory Altman, director of technology consultancy Altman Vilandrie & Company.

So who needs Dish the most?

Probably AT&T (T, Fortune 500), which has excellent spectrum but is quickly running out of it in many markets. Rubbing salt in the wound: AT&T had to give T-Mobile $1 billion worth of spectrum as part of the failed deal's breakup terms.

Despite that gift, T-Mobile still has the least spectrum of all the national carriers. It's also got the smallest supply of unused airwaves, according to the FCC. It has no path to deploying a 4G LTE network, and its parent company is eager to sell it off.

Sprint (S, Fortune 500) has by far the most available spectrum through its partnership with Clearwire (CLWR). But not all spectrum is created equal. Clearwire's is in such a high frequency band that signals travel very short distances and have terrible building penetration. That means Sprint has to build many more cell towers than it otherwise would.

Experts agree that Verizon (VZ, Fortune 500) is in by far the best position, with ample capacity for the immediate future -- particularly if its spectrum deal with the cable companies gains regulatory approval.

The nation's largest carrier also has the highest-quality spectrum. It's got a foothold in a large, contiguous band across the nation that experts liken to "beachfront property." Signals in that band can travel long distances and penetrate buildings. That enviable resource made it possible for Verizon to launch the nation's first and largest ultra-fast 4G LTE network.

But even Sprint and Verizon will need more spectrum within the next few years.

"You're seeing a move toward broadband and video on mobile devices," says Brian Clark, managing partner of MC Partners, a wireless venture capital investor. "There will be continued massive bandwidth needs, so it's not like companies' current spectrum holdings are fine and there's nothing to worry about."

Coming Thursday: Why the capacity crunch means your cell phone bill is going up. ![]()