The new king of luxury

Since taking the reins of one of the world's biggest fashion empires, Fran�ois-Henri Pinault has put his stamp on Gucci, YSL, and Puma. Now the luxury business is putting him to the test.

|

| François-Henri Pinault, chairman and CEO of luxury conglomerate PPR |

(Fortune Magazine) -- It's easy to envy the charmed life of Fran�ois-Henri Pinault.

He's the scion of a French family whose fortune exceeds $6 billion and whose holdings include the auction house Christie's and Ch�teau Latour, a top Bordeaux vineyard.

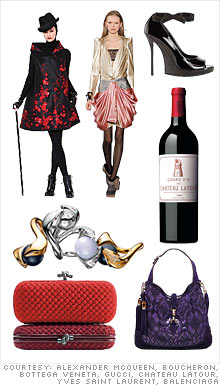

Since 2005 he has run the family's main asset, a publicly traded $28-billion-a-year conglomerate called PPR that owns some of the world's best-known luxury brands, including Gucci, Bottega Veneta, and Yves Saint Laurent. Stella McCartney works for him, as does enfant terrible designer Alexander McQueen.

On Valentine's Day this year Pinault (pronounced peen-oh) married Hollywood star Salma Hayek in a Paris ceremony and subsequently threw a masked ball in Venice for 150 of the couple's closest friends, including Edward Norton, Bono, Pen�lope Cruz, and Charlize Theron.

Yet for all the glitz, some harsh realities have been intruding into Pinault's kingdom lately. On an afternoon last March he spent three hours at a meeting in Paris with union representatives from various PPR businesses, talking about store closures, layoffs, and other cutbacks that he had put in place in reaction to the global economic crisis.

The meeting itself passed without incident, but as Pinault left, the taxi taking him back to his office was surrounded by angry employees protesting the cuts. They blockaded him in the car for an hour, hurling abuse and reading out a laundry list of demands, until police in riot gear came to free him. It was the highest-profile case of what the French call "bossnapping."

A video taken by the protesters and posted on YouTube shows Pinault, 47, in a dapper suit in the back of the taxi, uncomfortably chewing his fingers and studiously trying to ignore the rabble. Today he plays down the incident, saying, "I stayed stoic." Nonetheless, he admits, "it was intense."

Intense is, in fact, a pretty good way to describe Pinault's life at the moment as he confronts two challenges -- one financial, the other dynastic.

The financial one is that the $235 billion luxury market has taken a dive as consumers from Rome to Rodeo Drive slam their wallets shut and high-end department stores, including Neiman Marcus and Saks Fifth Avenue (SKS), slash prices to reduce stocks. Consultancy Bain & Co. estimates that global sales of luxury goods dropped between 15% and 20% in the first half of this year and will be down by 10% overall in 2009.

The dynastic challenge is less tangible but no less important. Industry watchers see the current crisis as a baptism by fire for Pinault's leadership skills. Will he be able to prove that he's a successful CEO in his own right, one who is at the helm of an empire founded by his father, Fran�ois Pinault, not because of who he is but because of what he can do?

So far the younger Pinault is off to a decent start. While many luxury brands are currently suffering, and two big European names -- Christian Lacroix and Escada -- have even filed for bankruptcy, Pinault has largely confounded the skeptics.

His bold $4.7 billion payment for a controlling stake in athletic shoe and clothing brand Puma in 2007 has helped buffer PPR from the luxury downturn. (The company now owns 70% of Puma.)

Pinault was also quick to spot the first signs of the consumption slump back in the spring of 2008 and rapidly imposed what he calls "wartime budgets" on all of PPR's divisions.

"He really saw it coming," says Ronald Frasch, president of Saks Fifth Avenue, who describes Pinault as "very engaged and with an innate feel for the business."

The ensuing tough cost cutting and inventory management have worked: On July 31, Pinault pleasantly surprised Wall Street by announcing that profits for the first half of the year fell 4.8%, to $1 billion, on revenue that was down just 3.6%, to $13 billion.

The luxury division, far from suffering the rout endured by some rivals, reported flat earnings and only a slight dip in operating margin. PPR stock jumped almost 30% on the news and has now made up for its steep 57% decline last year.

Those close to Pinault insist that he has gained markedly in self-confidence and stature with this crisis, and is well on his way to stepping out from under his father's shadow. Fran�ois Pinault senior, 72, thinks he's already done that.

"He has a lot of sang-froid," he tells Fortune, lauding his son's ability to take charge and make quick decisions. "I'm impressed - but don't tell him that. We're not a family that gives compliments easily."

Fran�ois-Henri Pinault might be a fabulously rich dauphin with an impossibly glamorous wife, but talk to his family, friends, and business colleagues, and they'll tell you that he's not stuck-up.

His father says, "He doesn't have the arrogance of some heirs. He was never brought up to think of his inheritance as a right, but as something he had to conquer."

Fran�ois junior -- who changed his name to Fran�ois-Henri to avoid being confused with Dad -- does display some of the trappings of great wealth: He used to tool around Paris in an Aston Martin sports car (later traded in for a Lexus hybrid), and he has a collection of more than 60 pricey watches, at least one of which he's tried to dismantle out of curiosity.

But when he's not flying off to see Salma and their 2-year-old daughter, Valentina, in Los Angeles or New York, he likes to play tennis, work out with a boxing trainer, and even entertain his friends' children with card tricks he's been honing ever since he was a teenager.

Charles-Henri Le Bret, an investment banker who has been friendly with him for 20 years, goes so far as to describe Pinault as "humble."

His father's business maxim is "Think like a strategist; act as an animal." (The family's holding company, Art�mis, is named for the goddess of the hunt.) While the father and son have a lot in common, there are differences.

"Fran�ois-Henri has a lot of imagination, but he's more rational and analytical. He's a down-to-earth, figures-friendly guy," says Serge Weinberg, former CEO of PPR, who has worked closely with both men.

Pinault's father was a high school dropout who started in the timber business and built PPR through a series of shrewd acquisitions over the years. From lumber, in his home region of Brittany, he moved into industrial goods and then into retail.

Pinault junior attended the elite French business school HEC in the early 1980s and joined the family business in 1987. He almost didn't. At one point after graduation, he was living in L.A. and became so enamored with life in America that he almost attended Stanford business school. Unable to get a green card, he moved back to France.

His father remembers it differently. Fran�ois senior says that when he saw how tempted his son was to stay in California, he raised the idea of Fran�ois-Henri's coming back to take over the empire.

First, Fran�ois-Henri had to prove himself in a succession of jobs that amounted to a 13-year apprenticeship, starting off as a lowly salesman in timber and doing stints in various businesses, including the African operations.

Throughout he has shown a fascination with tech that's clearly visible in his strategy as CEO. Back in the late 1990s he launched FNAC, the book and electronics store, on the web, where it still outsells Amazon in France. Overall some $3 billion, or about 8%, of PPR's revenue now comes from e-commerce. The lion's share is from PPR's U.S. catalogue operations and FNAC.

Then it was time. On a Friday in April 2003, Pinault senior handed the reins to his son in a scene that speaks volumes about their relationship. He took his son out to dinner at the Paris bistro Ami Louis, and as they sat and chatted he pulled out three interlocking gold rings that his jeweler friend Joel Rosenthal had made specially for the occasion.

Engraved on the first was the date 1963, which is when Pinault first created his company. On the second was 2003, marking when Fran�ois-Henri was to take charge. On the third was a question mark. Attached to the rings was the key to Pinault's office at Art�mis, located in an elegant townhouse just off Avenue Montaigne.

As the father recalls, "I put it on his plate and said, 'On Monday you're taking over.'" Fran�ois-Henri was stunned. "He first thought it was a joke," says Pinault senior. It wasn't. He cleared out his drawers at Art�mis that weekend, and on Monday his son moved in as chairman. Two years later Fran�ois-Henri decided to run everything, and took over from Weinberg as CEO of PPR, who had managed the company for ten years and saw it was time to move on.

The younger Pinault eschews micromanagement and has delegated operational responsibility to PPR's division heads. Before making big decisions, such as the Puma acquisition, he wants to hear different points of view from his lieutenants. And he cultivates informality -- he's given out his cellphone number to a wide range of staff, including designers like Tomas Maier at Bottega Veneta, encouraging them to call when they have an issue.

The flip side of this informality is that he sometimes seems ill at ease in more formal corporate settings. Early in his tenure as CEO, he sometimes turned red when making formal presentations to a roomful of staffers, according to current and former senior executives, although that now happens less frequently.

The Pinaults are different from many business families in that they lack any sentimentality about the companies they build. "Nostalgia kills happiness," says Pinault senior. "It can be a big danger to get too attached to a firm's activities."

Fran�ois-Henri shares that unsentimental vision. One of his first acts as CEO was to sell off the Printemps department store chain that was the middle "P" of PPR (for Pinault-Printemps-Redoute -- the last a catalogue fashion business).

"It's not the philosophy of the group to be unchanging," he says. "We're there to accelerate the development of a sector, to give a strategy, to put people in place, and then to grow it over 10 to 15 years." If that sounds uncannily like the goals of a private-equity firm, Pinault insists there's one major difference: "We don't define the exit. It's not based on ratios but on the degree of maturity of the business."

Pinault picked a good time to sell Printemps, at the height of the real estate bubble, and got $1 billion for the asset. The sale wasn't a big surprise -- it had been mulled internally for some time -- but his next move was: He used that cash to help buy a replacement P -- Puma.

Puma and PPR's other retail businesses strike some as an odd fit with the luxury group. Gucci's brands in 2008 accounted for just 17% of PPR's revenue but more than 40% of its operating income. In July, Luca Solca, a luxury-goods analyst at Bernstein Research, suggested breaking up PPR and floating off the luxury division as a "pure play" company. Others have called for PPR to sell FNAC and the home furnishings operations, which have languished in recent years and become a drag on earnings.

Pinault rejects such talk out of hand. The combination of mass retail, with its big markets but lower margins, and luxury, with much smaller sales but very high margins, "gives us both volume and resistance [to downturns]," he says, arguing that it's "coherent" to have both parts together. What's important in Pinault's world are brands, luxury or not, that have potential for rapid international growth. In Puma and the Gucci group he thought he had clear winners, and for a while they soared. Then the sky fell in.

In the fall of 2007, as PPR's management was drafting budgets for the following year, Pinault instructed them to take into account a probable economic slowdown. "We said, 'Watch out,'" he recalls. At an executive committee meeting in July 2008, Pinault slammed on the brakes.

The slowdown hadn't yet hit luxury and Puma. Still, from September, all the divisions shifted gears, working to reduce inventory and save cash. "In a recession you must be able to call into question everything you've done before," Pinault says.

Such talk is markedly different from that of Bernard Arnault, CEO of PPR rival LVMH, who publicly declared in 2008 that his company was effectively "immune" to recessions -- before he, too, had to slash spending.

Robert Polet, who was hired from Unilever to head the Gucci Group, says that an entire change of mindset had to take place -- "from managing high growth to planning for negative growth." Polet has cut capital spending by 25% to 30%, but selectively rather than across the board. China and some other parts of Asia are faring much better than luxury's core markets of Europe, the U.S., and Japan, and Gucci, Bottega Veneta, and Balenciaga have continued opening new stores there, even in the downturn.

Behind the scenes, all the brands have been scouring for ways to save cash. Hiring and salaries have been frozen since last September. Bonuses for this year have been halved too. Inventiveness has become the order of the day.

Polet tells the story of how he dropped in to Bottega Veneta's headquarters in New York City last November to find designer Maier on the floor with the brand's shoe manager, wading through a huge pile of books filled with samples of leather and skins. They were checking how much of each material they had in stock, planning to use it up in the next collections. "I left the room and thought, Wow," Polet says. "Finding ways to manage down inventory has almost become a sport."

Despite the cost controls, some of the group's brands are suffering, including YSL, which reported a $24 million operating loss in the first half.

Pinault, however, insists that the crisis has not altered the core attraction of luxury. "People are still buying it, and price perception has not changed," he says.

What has changed is that there's been a shift in demand, with consumers looking for less expensive entry-price items. At Saks Fifth Avenue, Frasch says the highest-priced items are still selling, as are the lowest ones, but the middle is getting squeezed.

Suits priced around $2,000 (yes, that's the middle) are now "very difficult" to sell, while they are still moving in the $900 to $1,500 range, he says. Dress shirts need to be under $200, and ties around $100.

After years of charging what they like, that's an adjustment for many brands, but Frasch singles out Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent as highly responsive to changing consumer demand. "I give them a lot of credit -- they're reacting very, very quickly," he says.

Will that be enough? Pinault remains cautious about the short-term outlook. But as this downturn plays out, one thing is certain: It's Fran�ois-Henri who is calling the shots.

Polet recounts how Pinault senior would sometimes stop by his London office during the first couple of years of his son's tenure as CEO for a one-hour chat. Near the end, he would ask, 'How are you getting on with my son?'" Polet relates. "I'd say, 'Okay.' Then he would say, 'Good. I'll show myself out.'"

That's now stopped. Pinault senior jokes that if he does drop in to a Gucci store these days, "It's only to check for dust." Speaking of his son, he says, "I follow his activity, but I'm not looking over his shoulder every morning to see what he's doing."

That's just fine by Fran�ois-Henri. He's in frequent contact with his father, but he's not about to dwell on the delicate issue of his filial relationship. "He's my father," he shrugs. PPR, Gucci -- and the gut-wrenching downturn -- are his children now. ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More