Where are the subprime perp walks?

Three years after the housing bubble popped, prosecutors have yet to bring a major case tied to the subprime fiasco. What gives?

|

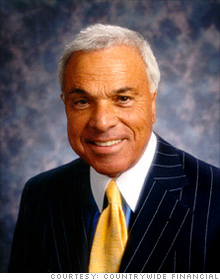

| Ex-Countrywide chief Angelo Mozilo is fighting SEC civil fraud and insider trading charges. |

NEW YORK (Fortune) -- Where are the perp walks for the subprime mortgage executives that dragged us into this mess?

Three years after the housing bubble popped, federal prosecutors have yet to bring a case against the executives whose firms took part in some of the worst excesses of the subprime mortgage market.

It's not like there's a shortage of abuses to investigate. The landscape is littered with the wreckage of financial institutions that crashed under the weight of bad loans, costing shareholders and taxpayers billions of dollars.

"Many" lenders that went bust were cooking their books before they collapsed, according to a 2007 FBI report. Meanwhile, top officers at many mortgage shops were pocketing hefty paychecks and stock sale proceeds.

And though it may be early to judge the law enforcement response -- corporate fraud cases can take a long time to assemble, thanks to their complexity and limited enforcement resources -- some observers are nonetheless struck by the lack of high-profile prosecutions.

"The perp walk has been remarkably absent during this crisis," said Steven Ramirez, a law professor at Loyola University Chicago, referring to the practice of parading a criminal defendant before the press on the way to court. "I don't think it's because of a lack of criminal activity."

Bank reports of mortgage fraud have quadrupled since 2004, according to FBI data. The agency says 80% of mortgage fraud loss cases involve industry insiders, and the cost of the cases it kept track of last year was well in excess of $1 billion.

The Justice Department and the FBI have reported some success in bringing some low-level fraudsters to justice.

Prosecutors in California last year indicted six people in a scheme to defraud Long Beach Mortgage, a subprime mortgage shop that was part of Washington Mutual, the giant Seattle-based lender that collapsed last year and was acquired by JPMorgan Chase (JPM, Fortune 500).

One defendant was sentenced to 15 months in prison and four others entered guilty pleas, Justice said. One participant in the scheme was a Long Beach employee who received $100,000 for making sure the firm funded fraudulent loans, the Justice Department said.

But some students of white collar crime are skeptical of the notion that the big subprime lenders were primarily victims of mortgage fraud.

Prosecuting low-level cases without holding highers-up accountable risks "trivializing" white collar crime -- and paving the way for the next round of financial shenanigans, said Henry Pontell, a criminology professor at the University of California at Irvine.

"We really have learned no lessons from the savings and loan crisis," he said, referring to the wave of bank failures in the 1980s that led to a number of notable fraud convictions. "The most germane one is that fraud plays a central role in these episodes. It acts as an accelerant for financial bubbles."

The only major criminal prosecution to come out of the financial crisis so far is a case due to go to trial next month against two former Bear Stearns hedge fund managers who are accused of securities fraud.

The biggest civil enforcement action is one the SEC filed in June against Angelo Mozilo, the former CEO of mortgage lender Countrywide.

The SEC accused him and two other Countrywide executives of insider trading and securities fraud, contending they misled investors by claiming Countrywide was lending prudently when it was making loans Mozilo himself labeled toxic in an internal email. Mozilo's lawyer called the allegations "demonstrably false."

Pontell says proof that fraud was rife at the big subprime mortgage houses resides in the lenders' files. Questions about borrowers' income or assets were answered, in some cases, by taping computer-generated figures to blank, pre-signed documents.

"These people were so brazen, they never bothered to take the cut-and-paste documents out of the files," Pontell said. "Arresting those guys is like catching the fish that jump into the boat."

But as shameless as the mortgage fraud might have been, connecting back office corruption with the executive suite isn't easy.

"The problem is finding the executives' fingerprints on the consumer files," said Peter Henning, a law professor at Wayne State University. "Angelo Mozilo may have set the tone at Countrywide, but there is no way you're going to find his fingerprints on any of those mortgages."

Countrywide -- now owned by Bank of America (BAC, Fortune 500) -- and some of its former hard-charging subprime competitors are also dealing with a wave of private civil suits.

New Century Financial, once the No. 2 subprime mortgage originator, filed for bankruptcy in April 2007 after admitting that its financial statements weren't correct. A judge last year allowed a securities fraud class action against it to proceed after noting "a staggering race-to-the-bottom of loan quality and underwriting standards."

Two of the firm's three co-founders made millions selling shares in the year before the firm's collapse. A third co-founder, Brad Morrice, who was CEO when it filed for Chapter 11, made $8.3 million in salary and bonuses between 2003 and 2005, the latest years for which data are available.

Morrice is now managing partner at consultancy Cypress Strategy Group. The firm's web site bears the slogan "I'm mad as hell and I'm not going to take it anymore."

Complicating matters for prosecutors are the rising demands on the Justice Department since the Sept. 11 terror attacks.

Corporate fraud prosecutions have fallen by two-thirds since then, according to Justice Department data tracked by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University.

"There has not been a lot of stomach for bringing big cases," said Ramirez. He said he was surprised that the Obama administration hasn't been more aggressive in prosecuting financial crimes.

The Justice Department rejects that critique. A spokesman notes that regulators have successfully prosecuted admitted investment fraudster Bernie Madoff and are pursuing a case against alleged bank swindler Allen Stanford, who was arrested in June.

But Pontell notes that unlike the S&L cleanup, which was funded by the passage of the Financial Institutions Reform Recovery and Enforcement Act, this crisis has brought no round of new money for the enforcement agencies from Congress.

That means the battle against what he calls the starched white collar criminals is competing for scarce resources with the wars on terror and drugs, among other things. And this battle is taking place while the still powerful banking industry is lobbying to keep regulation and oversight at low ebb.

Ramirez said that if Congress doesn't loosen up the purse strings for stronger enforcement, the bill for the next scandal could be even bigger.

"People say bringing these cases is expensive," said Ramirez. "But when you have laxity in law enforcement, the costs are off the charts." ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More