Search News

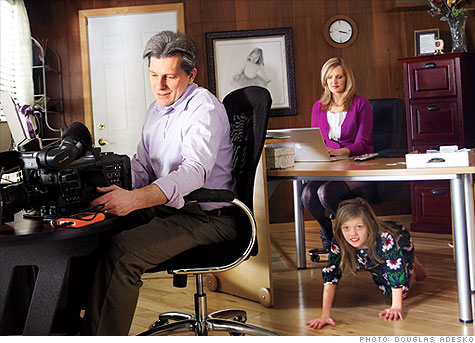

The Petersons work from home. Added perk: drop-in visits from daughter Cecily.

The Petersons work from home. Added perk: drop-in visits from daughter Cecily.(Money Magazine) -- Chris and Janie Peterson have an enviable life. They own a lovely 3½-bedroom ranch house just outside Minneapolis and have work schedules flexible enough to allow them lots of time with their children, Reece, 10, Cecily, 9, and Georgio, 7.

Chris, 54, is a freelance TV cameraman who shoots locally produced cable shows and pro football events. Janie, 42, loves being off the stressful fast track of her last job, where she earned about $200,000 a year as chief meteorologist at a Fox TV affiliate. That job ended in 2007, which is when Janie went freelance too, taking the occasional job acting in TV commercials and, with Chris, producing online videos for businesses.

|

| Freelancing gives the Petersons more time with Reece, Georgio, and Cecily. |

| MMA | 0.69% |

| $10K MMA | 0.42% |

| 6 month CD | 0.94% |

| 1 yr CD | 1.49% |

| 5 yr CD | 1.93% |

Last year they pulled in a combined $165,000; they have little debt and a net worth of more than $400,000.

But beneath this fetching façade is a shaky financial foundation. After paying for business expenses like video equipment and production costs, the Petersons' income is closer to $80,000 before taxes -- and they have not cut expenses enough to make up for the more than 60% drop in their income.

They have burned through most of their savings and have less than two months of living expenses in the bank. Clients often pay late -- or not at all -- creating a cash-flow nightmare that makes the arrival of Fred the mailman the biggest event of the day.

The individual health insurance policy they bought to replace Janie's group coverage at work has such a high deductible that they've sharply cut back doctor visits, skipping some routine care and going only when absolutely necessary.

They can no longer afford to contribute to retirement accounts and have just $7,000 saved for college for all three kids. They are living so close to the edge, in fact, that one financial emergency could wipe them out.

Despite the precariousness of the freelance lifestyle, households like the Petersons', in which both spouses work for themselves, are becoming more common. The reason is simple: Freelancing is where the jobs are.

In the last six months of 2009, as full-time positions continued to vanish at an alarming (if slowing) rate, employers went on a temp-hiring binge, adding 166,000 nonstaff positions. The trend helps companies cut costs but can wreak havoc on a family's finances.

"My question is whether freelancing is a financially viable lifestyle for the Petersons," says Colleen Weber, a financial planner in nearby Chanhassen, Minn., who met with the family at Money's request. "They can't take a vacation and are full of anxiety about whether to take the kids to the doctor. I'm not sure how long they can sustain that."

Janie Peterson met Chris Peterson in 1994 at the local Phoenix TV news station where they both worked. Since they had the same last name (though their families aren't related), they were treated as a married couple even before they tied the knot two years later.

When a weather story broke, the usual refrain was, "Let's send the Petersons!" Janie was no hairspray journalist -- she is certified by the American Meteorological Society -- and her rapidly advancing career took them to Pittsburgh, then St. Paul, and finally in 2000 to Fox 9 in Minneapolis, near where Janie grew up and Chris has family.

Around that time Chris decided to quit TV news, hoping he could make more money as a freelance cameraman than as a general assignment staffer. He landed a few gigs quickly, working with clients such as the Food Network and Animal Planet. Since Janie's job at Fox 9 was a part-time weekend weather shift (with benefits), she took care of their three children (born in rapid succession between 1999 and 2002) while Chris worked and vice versa.

But when she was promoted to chief meteorologist in 2002, that schedule was no longer feasible. The position came with a big pay raise -- she went from an $80,000 annual salary to $127,500 initially, plus bonuses -- but the hours (1 p.m. to 11 p.m.) were killer. Not comfortable sending the kids to day care, the couple decided Chris would become a stay-at-home dad.

The arrangement was tough on everybody. Chris was devoted to his work and had garnered multiple Emmy nominations. But the role switch meant he could take only morning jobs when Janie was home with the kids; as a result, he only earned $10,000 that year.

Another problem: "Technology changes so fast in my business that it was hard to keep up," he says.

Janie, meanwhile, was constantly sleep-deprived and heartbroken at getting to spend only a half-hour a day with Reece before he left for school. Plus, the demands of her job seemed unceasing: When she took an afternoon off to attend Cecily's music recital, a freak weather event -- high winds blew a window cleaner off his scaffolding into the windows of the skyscraper where he was working -- landed her in trouble at work for showing up to cover the story in her jeans rather than camera-ready attire.

So when a management shakeup led to Janie's contract not being renewed in 2007, she saw a chance to regain some balance in her life. Jobs in local news were getting tougher to find anyway, as viewership shrank with the expansion of cable channels and the Internet. Why not let Chris go back to the work he loved and have Janie spend more time with the kids? As a freelancer, she could help Chris get gigs, audition for commercials, and team up with her husband to make online videos.

But the prospect of giving up Janie's high salary and benefits was terrifying -- "I was panicked," she says -- because the Petersons knew they were not financially prepared for such a risky venture.

They had only $40,000 in the bank and $20,000 in mutual funds. Their lack of savings was partly the result of sometimes lavish spending -- when Janie was pulling down a big salary, she occasionally indulged in purchases like a $500 throw pillow.

The couple also shelled out $100,000 on renovations after buying their house in 2003, putting in new flooring, landscaping, siding, and a driveway. But their savings were also compromised by a deep aversion to debt. They had made a $110,000 down payment on their $425,000 house, paid off both cars, and made extra payments toward principal every chance they got. "I do not like debt at all," says Janie.

In the end, though, Janie considered it even riskier to keep placing her fate in the hands of corporate bosses in a declining industry. "I wanted to take control of my situation," she says, "instead of being at the whim of someone else."

The Petersons launched their dual-freelance life in early 2007 with a flurry of activity.

Chris says he felt unshackled. "I called everybody I knew and said, 'I can work every day now!' " Janie signed up with three talent agencies for help booking auditions and started cold-calling local advertisers to pitch their online video business. But her efforts yielded few paying jobs.

That first year, the amount the Petersons took home plummeted from $210,000 to $85,000. Making matters worse, more than a third of that money went to buy equipment they needed for their video business -- two new computers, the latest editing software, and a $13,000 videocamera -- leaving them with only $52,000 to live on.

They also staggered under the expense of replacing Janie's group health insurance from her old job. Retaining it through COBRA would have cost $1,500 a month, so they opted to buy an individual policy instead. At $516 a month, the coverage was far cheaper, but the $3,600 deductible meant the Petersons had to pay for all doctor visits and other routine care out of pocket; the coverage would kick in only for hospital stays or a serious illness or injury.

The family cut back sharply on spending, saying "no more" to vacations in Maine and "yes" to hand-me-down clothes for the kids from relatives. But they were still spending far more than they earned: The van suddenly needed repairs, there were Christmas gifts to buy, they needed cash to pay a $4,500 bill for life insurance that had slipped their minds. To make ends meet, they had to tap $22,000 in savings and cashed out mutual funds for another $10,000.

By the summer and fall of 2007, though, business had started to pick up. Janie had landed them an $8,000 video project for General Mills, and Chris was paid $10,000 to shoot a commercial for a gas company.

"We just hadn't been prepared for how long it took for clients to make business decisions," she says. They also learned theirs was a seasonal endeavor, with more demand for outdoor shoots during the warmer months. Sure enough, jobs picked up the following spring, and they ended 2008 with revenue of $136,000, a big jump over their take in 2007.

When their revenue increased again in 2009, the Petersons began to believe they could really make their new life work. As the unemployment rate soared last year, they felt they had more job security as freelancers able to get work from a variety of sources than if they were on staff, dependent on a single company or a single boss.

And yet the Petersons can't avoid the grim fact that they are down to their last $11,000 in savings. Meanwhile, their monthly health premiums are up to $750 a month and, because of the high deductible, Chris and Janie haven't had full physicals in three years, even though heart disease runs in his family and colon cancer in hers. When Reece gashed his knee falling off his scooter, Janie hesitated before taking him to the emergency room, concerned about the bill. The outcome: five stitches and a total outlay of more than $1,000. "I'm always worried somebody will get ill and we won't be able to pay for it," says Janie.

The Petersons do have a fallback. If their savings run out, they have a $30,000 home-equity line of credit they can tap; they've dipped into it a few times already but have always managed to repay what they borrowed quickly once checks from clients arrived.

As for paying for college, the Petersons hope that by the time Reece is ready to enroll in eight years, he can save money by living at home and taking classes online.

And their own retirement? The couple seem resigned to work until they drop. Until then, the Petersons' strategy is to work hard and hope for the best. "I just try to have a good, positive attitude," says Chris, "and not sweat the small things."

Blind faith is not enough to get the Petersons on sound financial footing. Financial planner Colleen Weber recommends these steps:

Build an emergency reserve: The Petersons should have at least $30,000, or four months of living expenses, tucked away in a savings account so they can pay their bills on time, even when their clients pay late, says Weber. Eventually they should bump that up to the ideal target for freelancers: six months to a year of readily accessible funds.

To get there, the couple should stop making extra mortgage payments and redirect that money into a savings account. Next, take out a $30,000 business line of credit and tap it to pay all business expenses, until they've hit the goal for their emergency fund.

Using a business line of credit is preferable to borrowing from their HELOC, says Weber, because the loan won't be secured by personal assets, and the interest deduction is more valuable.

Smooth out cash flow: Once their savings swell, the Petersons should create a system to pay themselves just as if they had a regular job by setting up a biweekly automatic transfer of $3,500 from their business to their personal accounts to cover living expenses. That will end the daily drama about when the mailman will arrive, creating both peace of mind and budget discipline.

They should also set up a separate savings account for taxes, transferring in 25% of every payment they receive from clients to cover Social Security and Medicare taxes as well as income taxes.

Take advantage of tax breaks: Weber urges the Petersons to be more scrupulous in keeping track of the many work deductions freelancers are allowed. Among them are write-offs for a home office, business supplies, Internet access, phone lines, and travel for work.

They can also deduct their health insurance premiums, as well as any money they contribute to their health savings account to pay out-of-pocket medical expenses (including their deductible), up to a maximum of $6,150 for family coverage in 2010.

Create your own benefits package: Unfortunately, it's unlikely the Petersons will be able to find an affordable health plan with better coverage than their high-deductible policy. So they don't sweat how they'll pay every health-care expense they face, Weber suggests they set up automatic biweekly transfers of at least $200 into their HSA -- about what they spent out of pocket last year, excluding premiums -- and then tap that account to pay their medical bills as expenses arise.

The couple have gone without disability insurance but that's a big mistake, Weber says. She urges both Chris and Janie to get individual disability policies that will replace 70% of their income for five years if illness or injury prevents them from working. To keep the premiums down, the planner suggests opting for a 90-day waiting period before benefits kick in, vs. a 30-day policy. Likely cost: around $1,500 a year each.

Weber also advises them to dump their whole-life policies ($250,000 for her, $190,000 for him), and go with 20-year term coverage instead. They'll get a much higher payout ($500,000 each), while saving $2,000 a year.

Once they've beefed up their emergency fund, the Petersons should start saving again for retirement. To retire comfortably at age 70, Weber estimates they'll need to put away $20,000 a year, first by maxing out Roth IRAs ($6,000 for him because he's over 50; $5,000 for her) and then in a Simplified Employee Pension, the self-employment retirement account that's tax-deductible. The advantage of using a Roth is they can withdraw their contributions if needed, without penalty. That effectively adds $11,000 a year to their emergency fund.

The Petersons will be hard-pressed to sock away that much money for retirement; Weber estimates that to maintain their current lifestyle and set aside what they need for retirement, the couple would have to gross twice as much as they take in now. Janie believes that's feasible and is full of ideas about how to reach that goal, including branching out into weather forecasting for corporations and expanding their production company into marketing for social media forums like Facebook and YouTube.

But even if the Petersons can't engineer a financial turnaround and Janie is forced to look for a staff job again, she says their adventure in freelancing will have been worth it. She'll never forget the anchorman colleague who told her his son was graduating from high school and how much he regretted missing the boy grow up.

"All the time I've spent with my kids -- taking them to hockey practice, meeting them at school for lunch -- that's irreplaceable," Janie says. "Would I do this again, knowing in advance what it would do to our finances? No question about it."

Money magazine is looking for Detroit families (including people who have recently moved away) who are willing to discuss their finances and are looking for financial advice. If interested, email your contact information to gmannes@moneymail.com. ![]()

| Overnight Avg Rate | Latest | Change | Last Week |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 yr fixed | 3.80% | 3.88% | |

| 15 yr fixed | 3.20% | 3.23% | |

| 5/1 ARM | 3.84% | 3.88% | |

| 30 yr refi | 3.82% | 3.93% | |

| 15 yr refi | 3.20% | 3.23% |

Today's featured rates:

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |