Search News

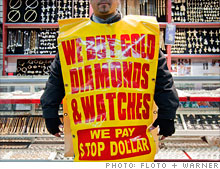

A scrap-gold buyer with purchased items in a shop on Manhattan's 47th Street

A scrap-gold buyer with purchased items in a shop on Manhattan's 47th Street

FORTUNE -- I'm standing in a stream in upstate New York shoveling dirt into a bucket. Danny Miller, a 58-year-old retired industrial engineer, shows me how to scatter the dirt into a sluice propped against rocks in shallow water. He dumps the residue from the sluice into a green plastic pan and shakes it, looking for "color." "I almost thought I saw a little piece of gold," says Danny, who heads the New York chapter of the Gold Prospector's Association of America. "Boy, I thought I saw a speck there for a second."

Danny, there is no gold in your pan. There's no more than a few specks in this whole damn stream. In fact, all the unmined gold in the entire state of New York would probably fit into that one-ounce vial your buddy Zeke gave me before we headed into the woods. Worse, you explained all these dismal facts to me before I flew all the way to Syracuse, then drove another hour to meet you and seven other members of this nutty little club at a firehouse in West Eaton, N.Y. A giant American flag hung on the wall near the pool table as club member Kenneth Roman, 64, told the group that so far he has found exactly four specks -- "about a quarter the size of fly poop." Then you reminded us that according to an archaic law, any gold we do find belongs to the State of New York.

|

| A shop on Canal Street in New York |

So what in the world are we doing out here?

Danny and the gang say they're not disappointed if they don't find gold -- they just love being outdoors. The truth is a bit more complicated: Danny and millions all over the world have caught gold fever, a condition that disrupts normal cognitive processes. With the price of gold tripling over the past five years -- reaching $1,400 per ounce in November -- it is an increasingly widespread disorder. Once primarily the obsession of libertarians, survivalists, and conspiracy freaks, gold appears to be going mainstream. When even a barren state like New York gets its own chapter of the GPAA (launched in February), you know something strange is going on.

People are rummaging through their dressers for gold rings and bracelets to sell through Kmart, Sears (SHLD, Fortune 500), or to a new cash-for-gold company, Gold Promise, that rescued Mr. T from oblivion to become its pitchman. Gold vending machines are selling out in Abu Dhabi and Germany and heading to the U.S. Cable ranters from Jim Cramer to Glenn Beck urge viewers to buy gold. Hedge fund heavyweights like John Paulson and George Soros have loaded up, gold-mining stocks are hot, and exchange-traded funds have made it easy for average investors to own physical gold without having to bury bullion bars in their backyards. The president of the World Bank has suggested creating a modified gold standard for world currencies.

There is remarkably wide agreement that gold is or soon will be a bubble -- "The ultimate asset bubble is gold," Soros said earlier this year -- and the biggest question seems to be whether it will burst years from now or next week, the day after you bet your life savings on Krugerrands. And yet gold feels different from other recent manias, with none of the futuristic cool of tech or the flamboyance of real estate. Gold has a serious image problem, more redolent of Lyndon LaRouche than Steve Jobs. That's why your friends may be buying gold without admitting it, lest you think they'll start spouting paranoid theories about why there hasn't been an independent audit of the gold in Fort Knox since the Eisenhower administration. This makes it a queer, stealth mania, though it seems only a matter of time before -- wait a minute, why hasn't there been an independent audit of the gold in Fort Knox?

Confessions of modern-day gold investors

It's late October in the overflowing main ballroom of the Hilton New Orleans Riverside. Newt Gingrich and Dick Armey are onstage exulting over the impending Republican takeover of the House, columnist Charles Krauthammer is decrying the "parasitic" public workforce, and author Robert Ringer wonders where in the Constitution it says the government has the right to redistribute wealth. In the back row, a 32-year-old real estate agent from Alaska named Gerardo Del Real is shaking his head. "It makes me cringe," he says.

Del Real, you see, is an Obama supporter. The fact that someone like him is attending the New Orleans Investment Conference for the second straight year is a sure sign that gold mania is spreading beyond the fringe "God, guns, and gold" crowd. The event was founded in 1974 by a gold bug named James U. Blanchard III, who once hired a biplane to tow a "legalize gold" banner over President Nixon's inauguration (private ownership of gold was legalized in 1974). Many of the same 700 or so older white libertarians come here year after year to seek investment advice, listen to speeches, and hone their gold strategy: Physical or paper? Coins or bars? ETFs or mining stocks?

They also get an earful of conspiracy theories, like the one about how the U.S. government has been secretly swapping gold with other central banks to keep the price artificially low and prevent gold from competing with the dollar -- that's why there has been no independent audit of the gold in Fort Knox for more than 50 years, according to Chris Powell of the Gold Anti-Trust Action Committee, who spoke here. But gold is rising anyway. With paper currencies collapsing, government debt out of control, and the Fed pumping billions into the economy, the general consensus here is that the world is going to hell in a handbag. This creates an atmosphere of doomsday glee, summed up by Gary Alexander, emcee for the Gingrich-Armey panel: "All these crises have been very good for gold!"

The main motivations for buying gold, says conference host Brien Lundin, editor and publisher of Gold Newsletter, are the usual culprits: fear and greed. Del Real is happy to align himself in the greed camp, though he adds that it's on behalf of his wife and three children back in Anchorage, his Mexican immigrant parents, and the domestic-violence shelters and artists he wants to support. With slicked-back hair and the affable air of a born salesman, Del Real made some clever investments during the real estate boom and emerged with $90,000 before the bubble burst. Now he sees another boom in the making and is hoping for a big score, putting 85% of his money in junior gold exploration and mining stocks that carry considerable risk but enormous potential. "I'm not a geologist, but I am a decent judge of character," Del Real says, convinced he can find the honest players in an industry where the truth can be as hard to find as 24-karat nuggets. As we ride the escalator down to yet another gold workshop, he says, "I feel so lucky to be alive right now -- this is such a great time in history!"

At the opposite end of the emotional spectrum are Dewey Mundwiller, 70, and his wife, Sandy, 56, financial advisers in St. Louis who are attending the conference for the first time. They never seriously considered investing in gold until the crash of 2008. With a low-seven-figure portfolio in stocks and cash, they had thought they were set for life, but now they're terrified of losing it -- to either runaway inflation or an economic cataclysm. They are leaning toward putting 10% of their holdings in some combination of gold CDs, mining stocks, and coins. "Fear is motivating me," Dewey admits over dinner at Antoine's Restaurant in the French Quarter. "I don't know that the economy is going to fall off a cliff, but in case it does, I want to have some options."

Will the story of gold mania validate Del Real's exuberance or the Mundwillers' dread? Either way, such volatile emotions don't seem conducive to rational thinking about investments -- unless you're Newt Gingrich. The former Speaker of the House and potential presidential candidate in 2012 believes economic conditions make gold seem like an eminently sensible option.

"There's probably a base below which gold doesn't fall," Gingrich told me after his panel discussion. "Therefore, if you think in catastrophic terms, you buy gold as a hedge against the downside. And there's a risk of genuine inflation, in which case you're buying gold as a hedge against inflation. They're different but parallel tracks. And if you think both could happen -- that is, the stock market could collapse or inflation in the Weimar sense took off, or in the Third World it took off -- then gold is a rational investment."

Armey, who has a Ph.D. in economics, is blunter. The former House majority leader turned lobbyist turned Tea Party leader tells me backstage that people are being driven to gold by "the "irresponsible debauchery of the currency."

And yet both Gingrich and Armey admit they don't actually own any gold themselves. "I'm probably more traditional in my expectation that over the last 120 years, very long-term investments in the stock market work," Gingrich says.

Gold: The one true currency?

Leaving New Orleans, I decide to call on some hedge fund managers. Several hedge fund titans widely credited with bringing gold into the mainstream by taking strong positions -- John Paulson, Eric Mindich, and David Einhorn -- decline to be interviewed. But Richard Hurowitz, the 36-year-old manager of a $1 billion boutique fund called Octavian Advisors, agrees to break it down for me.

A history major at Yale, Hurowitz argues that our current infatuation with gold is actually in keeping with ancient cultural patterns. Gold is a currency, not a commodity, he says, because it has few real-world uses beyond jewelry, dentistry, and computer parts. It has always been accepted as payment around the world, and it is far more stable than dollars or yen because its sole issuer, Mother Nature, follows an extremely tightfisted monetary policy: All the gold ever mined would fill up fewer than four Olympic-size swimming pools.

While there has been much outcry over the U.S. government's expansion of the money supply and debasement of the currency to stimulate the economy and increase exports, Hurowitz points out that Cleopatra did basically the same thing. "Her father had run up huge debts, so the first thing she did was to stop issuing gold and silver coinage and only issued bronze coinage," he says. "Debasing the currency immediately solved the issue."

As paper money loses its value, the price of gold jumps. That's why libertarians consider it the one true currency, more reliable than the "fiat" legal tender issued by the state. That's also why Hurowitz's fund got into gold for the first time during the financial crisis of 2008, when the U.S. government cranked up the printing presses. Octavian began investing in gold-mining companies, which now make up a substantial portion of its holdings. Hurowitz especially likes a firm called Centamin Egypt Ltd., which recently began production in an area of central Egypt that has been mined for 4,000 years, dating back well before Cleopatra. "If gold does next year what it did this year, it'll go to $1,800," he says, pulling it closer to gold's inflation-adjusted all-time high of $2,387 in 1980.

Other well-heeled investors seem to share his optimism. According to a November survey of the high-net-worth members of the Tiger 21 investment club, 56% of respondents have a gold position in their portfolios, about equally divided among physical gold, ETFs, hedge funds, and mining stocks. This was the first year the group even posed the question in a survey, and no member had previously ever mentioned owning gold.

The age of home gold parties

"Hello, my name is _____. Last night I was with Brad Pitt. He put his butt in my underwear. And I said, 'Wow!'"

A dozen women erupt with squeals of laughter, pound their thighs, and begin chattering in rapid-fire Italian and English. I'm in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn at a gold party, the modern equivalent of the Tupperware party, where Joanne Amato and her mom, Rosaria, have invited a group of friends over to sell their scrap gold and silver. The ladies sit on furniture wrapped in protective plastic and sip white wine as Joanne breaks the ice by asking each guest to list her favorite leading man, male body part, undergarment, and verbal expression. When she strings the answers together, hilarity ensues.

In the kitchen, Scott Simon of the Gold Standard, a gold-buying firm based on Long Island, has set up his pennyweight scale and slate-and-dye kit for determining karats. One by one the women file in to have their old jewelry weighed and receive a cash offer -- 80% of the spot price of gold, with Simon and the hostess splitting the remainder. The invitation read, "Eat Drink Laugh/Leave With Cash."

Later Simon tells me this is hardly the most risqué party he's done -- one included sex toys and another featured competitive teams of burlesque dancers. Otherwise it's a normal night, if a bit slow -- he buys only about $1,215 worth of jewelry (the average is closer to $3,000). Amato, who has organized three gold parties, says she has noticed women becoming far less embarrassed about letting friends know they are selling jewelry. "It used to mean you couldn't pay your bills," she says. "Now they're much more comfortable with it." Tonight's guests could save the hostess's 10% commission by going to a local jewelry store, but most of them don't mind because this party is so much more fun than going to the mall or a pawnshop.

What's more uncomfortable to these women is buying gold jewelry. With the price of gold rising, many young couples can't afford gold wedding rings anymore, and the recession has devastated the jewelry industry. Simon says his family sold its manufacturing business a few years ago and is now prospering by buying scrap gold -- the company owns nine gold-buying stores in the area and is opening a new store in Manhattan this month. Last year twice as much gold was melted down from scrap jewelry as was used to make new jewelry in the U.S.

Making a living in gold

Gold still has deep cultural roots in countries like India and China, where the jewelry market is expected to explode along with economic growth. But in the U.S., gold is viewed less and less as a precious material and more as a currency, with as much emotional weight as a dollar bill.

It's a currency that doesn't require a job to obtain, which makes gold prospecting a tempting option for the masses of the unemployed or retired folks without enough savings. On my way home from the gold party I remember standing in the stream as Danny explained that although he's not motivated by economic necessity, he often drives to places like Michigan or North Carolina because there's a lot more gold there and, as in most states, it's legal to keep what you find. "With gold as high-priced as it is, it doesn't take much to get a day's wages to feed yourself and survive," Blake Harmon of the GPAA told me. "One twentieth of an ounce is worth $65 to $70 now, so it's not out of the question for someone to do that every day on a regular basis."

Beats working at Wendy's (WEN). If I couldn't find a job, what would I do? I have a wife and child to support. You can buy a sluice for $100, a pan for $8, and my pair of Muckmaster boots set me back only $120. GPAA members can camp out on their mining properties for months, so we'd definitely save on rent. If I got really ambitious, I could pick up a suction dredge/sluice with a Honda (HMC) engine from Keene Engineering that sells for $1,999 online -- or its top-of-the-line model for $14,350.

In the prospecting world, they call this "mining the miners" -- and we all know that the people who struck it rich during the California gold rush weren't the 49ers, but makers of picks and shovels. Still, buying that suction dredge would seem like a smart investment if I could find enough color to support my family -- and who knows? Maybe gold prices will keep climbing, to $2,000 an ounce, or $5,000, or more if the economy continues to tank. Danny's friend Zeke told me that he was going to take his buckets home to run the dirt under a microscope. Great idea. When I got home I stood over the kitchen sink for a very long time, washing the dirt off my boots, looking for gold. ![]()

| Overnight Avg Rate | Latest | Change | Last Week |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 yr fixed | 3.80% | 3.88% | |

| 15 yr fixed | 3.20% | 3.23% | |

| 5/1 ARM | 3.84% | 3.88% | |

| 30 yr refi | 3.82% | 3.93% | |

| 15 yr refi | 3.20% | 3.23% |

Today's featured rates:

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |