Search News

Just-harvested soybeans are stacked high at a Cargill grain elevator in Albion, Neb.

FORTUNE -- Greg Page's only misgiving about the job offer he received from Cargill in 1974 was that it was from Cargill. He had grown up in tiny Bottineau, N.D., six miles from the Canadian border. His dad was the local John Deere dealer, who also owned an 800-acre hobby farm with 40 cows. "Cargill has historically had probably mixed sentiments about it out on the prairie," says Page. "That's who you sold your grain to." Farmers knew that if they didn't keep their wits about them, they might well get squeezed by the food giant. You knew to "keep a weather eye out," he says.

Page took the job anyway. He labored happily "in close proximity to livestock" for his first 24 years at Cargill, beginning with the feed division, then in meat, at home and abroad, until he was picked for bigger things. Eventually he was promoted all the way, in 2007, to chairman and CEO of the country's largest private company. Today he runs a business that is vastly larger and more influential than the Cargill of his youth.

|

| CEO Greg Page has spent his entire 37-year career at Cargill. The business he runs today is vastly larger and more influential than when he started. |

With $119.5 billion in revenues in its most recent fiscal year, ended May 31, Cargill is bigger by half than its nearest publicly held rival in the food production industry, Archer Daniels Midland (ADM, Fortune 500). If Cargill were public, it would have ranked No. 18 on this year's Fortune 500, between AIG (AIG, Fortune 500) and IBM (IBM, Fortune 500). Over the past decade, a period when the S&P 500's revenues have grown 31%, Cargill's sales have more than doubled.

But those numbers alone don't begin to capture the scope of Cargill's impact on our daily lives. You don't have to love Egg McMuffins (McDonald's (MCD, Fortune 500) buys many of its eggs in liquid form from Cargill) or hamburgers (Cargill's facilities can slaughter more cattle than anyone else's in the U.S.) or sub sandwiches (No. 8 in pork, No. 3 in turkey) to ingest Cargill products on a regular basis. Whatever you ate or drank today -- a candy bar, pretzels, soup from a can, ice cream, yogurt, chewing gum, beer -- chances are it included a little something from Cargill's menu of food additives. Its $50 billion "ingredients" business touches pretty much anything salted, sweetened, preserved, fortified, emulsified, or texturized, or anything whose raw taste or smell had to be masked in order to make it palatable.

Despite Cargill's extraordinary size, strength, and breadth, it has long been remarkably successful at keeping out of the public eye. But the days when the company could get away with saying nothing and revealing less are over. "I think the world has curiosity about where its food comes from that is more earnest than it's been in the past," says Page, who earlier this year took the unprecedented step of allowing Oprah's cameras inside a Cargill slaughterhouse. (No video of the actual slaughtering, however.)

The simple fact is that the bigger Cargill gets, the more attention it draws. Timothy Wise, research director at the Global Development and Environment Institute at Tufts University, points to several factors that have increased concerns about Cargill's rising power, including recent wild gyrations in commodities markets, "sticky-high" prices at the supermarket, and the ever deeper integration of Big Ag with global financial markets. Perhaps the most hot-button issue of all is food safety. In August, Cargill announced the largest poultry recall in U.S. history -- 36 million pounds of ground turkey linked to a salmonella outbreak at a factory in Arkansas that sickened 107 people in 31 states and killed one. "The public is justified in being wary of having any part of our food system controlled by a small number of large corporations," says Wise.

With wariness comes intense scrutiny of Cargill's motives and its means: from organizations like Rainforest Action Network, worried about Cargill's impact on Indonesian and Brazilian ecosystems; from Congress, concerned about antitrust issues and speculative trading strategies; and from the international community. Food security -- the challenge of feeding the world -- has recently risen to the top of the G20 agenda. The UN says that a billion people go to bed hungry every night, and that we need to double food production by 2025 just to keep up with population growth and better diets in the developing world -- grim truths that concern Cargill deeply, whether Cargill believes that solving world hunger is its job or not. "We're not a philanthropy," says Page, in one of a series of rare interviews that Cargill granted to Fortune over the past several months. "I think we have to be careful not to lay claim to an altruism that doesn't exist."

And then there's climate change. It's hard to think of an organization anywhere in the world with a bigger stake in understanding potential disruptions to the food supply wrought by global warming than Cargill. Page does not disagree, although his take may surprise you. "Clearly the volatility can be an opportunity," he says, acknowledging that sharp price swings can play to Cargill's vaunted trading expertise. Then he adds, "The big part of our business is the physical handling of tens of millions of tons of food. If we believe the world is headed toward a varied weather pattern, those services become more important."

In other words, signs point to Cargill's influence -- and profits -- continuing to grow. But is what's good for Cargill good for the world?

Keeping it in the family

At 60, even in a clean white shirt and rimless spectacles, Page still looks like a farmer. He's tall and angular with thick silver hair, ruddy skin, and a chin like a block of wood. His accent is pure nasal prairie. I met him at Cargill headquarters, in Wayzata, Minn., just west of Minneapolis, in the Founders Room, surrounded by oil portraits of CEOs past. No matter what Page does to distinguish himself, his portrait will never hang here. The Founders Room is only for Cargills and MacMillans, the two families joined by marriage at the turn of the last century; they built Cargill and ran it as a family business until CEO Whitney MacMillan's retirement in 1995.

Page is the third CEO in a row to come from outside the family. Today not a single Cargill or MacMillan remains in a senior executive position at the company. Outsiders (six) and managers (five) outnumber family members (five) on the board. What hasn't changed is ownership. Cargill introduced a limited employee stock ownership plan in the '90s that allowed some family members to cash out. However, roughly 100 descendants of the founders still own around 90% of the stock, worth some $52 billion as of the last official tally. Generally, they've been content to plow profits back into the business and watch the value of their asset grow. Dividends are calculated on a rolling two-year cycle and paid at a rate that Page describes as de minimis. "The capital's not only private," he says, "it's patient and permanent."

Cargill's roots lie in the ancient, risky business of buying, storing, and selling grain. William Wallace Cargill, the second son of a Scottish sea captain, started with a single warehouse in Conover, Iowa, in 1865. Conover is a ghost town now, but Cargill still deals heavily in grain. Wherever it grows and wherever it goes.

Cargill ships other commodities too: soybeans and sugar from Brazil; palm oil from Indonesia; cotton from Asia, Africa, Australia, and the Deep South; beef from Argentina, Australia, and the Great Plains; and salt from all over North America, Australia, and Venezuela. The company owns and operates nearly 1,000 river barges and charters 350 oceangoing vessels that call on some 6,000 ports globally, ranking it among the world's biggest bulk shippers of commodities. "In one sense, you can think of Cargill as just a big transportation company," says Wally Falcon, deputy director at the Center on Food Security and the Environment at Stanford University. "Their game is: extremely efficient, high volumes, low margins, and just being smarter and quicker than anybody else."

Sometimes the same ship that picks up a load of soybeans at Cargill's deepwater Amazon port in Santarem, Brazil, after unloading in Shanghai, will carry coal from Australia to Japan before rinsing out its holds and returning to Brazil for more beans. In fact, Cargill's ocean-transport business moves more coal and iron ore for third parties than it does foodstuffs, oils, and animal feeds for itself, by a factor of two. "From places of surplus," to quote the Cargill mantra, "to places of need."

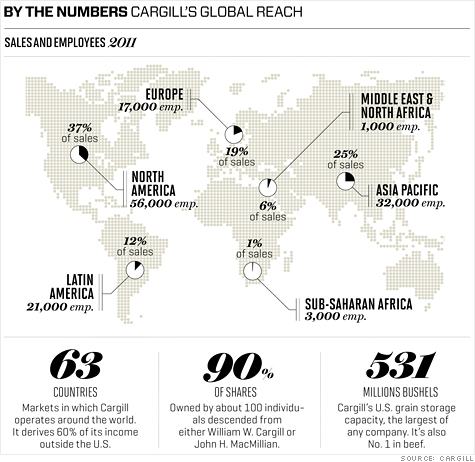

Cargill reluctantly sold its 64% stake in fertilizer manufacturer Mosaic (MOS, Fortune 500) for $19 billion earlier this year, and it exited the seed-engineering business long ago. But farmers in many of the 63 countries where Cargill operates -- 60% of earnings are generated outside the U.S. -- can still buy everything they need to plant their crops and feed their livestock from a local Cargill rep, as well as crop insurance, hedging instruments, and marketing advice.

The company has a long, if underappreciated, tradition of developing innovative new businesses. Cargill was the first commodities trader to set up shop in Geneva in 1956; others followed, and today Geneva is the center of the commodities-trading universe. In 2003, Cargill created an independent subsidiary called Black River Asset Management, a $5.6 billion hedge fund that leverages the company's unmatched global intelligence-gathering capability to make big bets on commodities and land on behalf of pension funds and university endowments. Among Cargill's many units is one, growing 15% a year, that's dedicated to replacing petroleum-based oils and lubricants with products made from plants. And the company recently brought to market a new no-calorie sweetener, Truvia, made from the white-flowered stevia plant, that has quickly become the No. 2-selling sugar substitute in the U.S. "We like to add new capabilities in the same way that we like to expand into new geographies," says Cargill's British-born vice chairman, Paul Conway.

One business Cargill is not in, curiously, is farming. With the exception of two large palm plantations in Indonesia, Cargill does not own land. That's partly a capital-deployment choice, much like its decision to charter, not own, ships. (Cargill has owned ships in the past, though, and may own them again soon. Cargill's former head of ocean shipping, Gert-Jan Van den Akker, who now runs the company's energy, transportation, and industrial businesses in Asia, told me he sees a "pure trading opportunity" developing in the next four or five years and has set up a partnership to buy distressed shipping assets: "We will buy when things are looking bad and at times sell when things are looking better.") But it's more fundamental than that. "They're not corporate farmers," says Shonda Warner, a former Cargill trader who went on to Goldman Sachs (GS, Fortune 500) and now runs an investment firm, Chess Ag Full Harvest Partners, that buys farmland. "Farming is not their business. Grain handling and grain trading -- trading the produce -- is their business."

That means stimulating new markets, opening new trade routes, matching producers with consumers, and, above all, ensuring steady flows of agricultural commodities in a changing global environment. "As far as how our corporate strategy works," says Conway, "we don't say, 'We think the world's going to look like this, let's define our strategy for that world.' We say, 'We don't know what the world's going to look like. We need a strategy or a set of strategies that can be successful almost irrespective of what the world looks like.'" Which helps explain how Cargill got into the cocoa business in Vietnam.

Bringing Cocoa to Vietnam

Seventy percent of the world's cocoa grows in West Africa, and most of that in one country, Ivory Coast. Since 1999, Ivory Coast has been through a bloody succession of military coups, rigged elections, and civil wars. "We were concerned about running into a ceiling on production there," says Harold Poelma, managing director of Cargill Cocoa. So Cargill began looking for other options. The solution that it came up with perfectly illustrates the company's global reach and long view.

Cocoa trees look like something Dr. Seuss would draw, with clusters of hard-shelled pods, as big and colorful as Halloween gourds, sprouting directly from the trunk and limbs. They don't grow just anyplace. They need shade, warmth, and humidity, as well as deep, rich soil -- conditions generally found within a band 20 degrees north and south of the equator. That band passes through Vietnam.

Cargill was one of the first U.S. multinationals to return to Vietnam when President Bill Clinton normalized relations with the government in Hanoi in 1995. Today it is the country's largest domestic producer of livestock feed and a central player in Vietnam's fast-moving shift from a state-controlled agricultural economy to one where small farmers are encouraged to work private plots for private gain. The effect of that shift has been transformative. Not long ago, Vietnam was importing a million tons of rice a year. Last year it became the world's second leading rice exporter. "Same people, same land," Vietnam's director of crop production, Dr. Nguyen Tri Ngoc, told me in his Hanoi office, speaking through a translator. "Before, farmers were not really farmers. They were workers in the fields, and they worked under the supervision of the government." And the difference now? "Free markets!" he says in English.

In 2004, Cargill launched a public-private partnership with one of its biggest customers, chocolate giant Mars, and the governments of Vietnam and the Netherlands. The aim: to create something that had never before existed in Vietnam, a cocoa-export economy.

First, Cargill had to convince a front line of growers to switch to cocoa from well-established crops like coffee, black pepper, and cashews. Two years before the first harvest (it takes at least that long for cocoa seedlings to produce fruit), before there was anything to buy, Cargill opened two fully staffed cocoa buying stations on major roads, in Ben Tre and Dak Lak provinces. It made an early commitment to transparency, posting on the Cargill website and offering by text message both the daily international price on the London market and what Cargill is paying locally; growers can lock their price for three weeks, the time it takes to ferment and dry the beans after harvest. Cargill also built a network of more than 100 demonstration farms, where curious growers can learn from their neighbors. And in February 2011 the company took delivery of the first Vietnamese cocoa beans to carry UTZ certification -- an independent sustainability program through which growers can earn an extra $100 per ton.

This year Vietnamese farmers will produce about 2,500 metric tons of cocoa, 70% of which will go to Cargill. That's a tiny sliver of the 3.4 million-ton global market, but the growth trend is impressive: 40,000 acres under cultivation in 2010, compared with 1,200 in 2003, and already 32,000 active growers in 12 provinces. Poelma sees the potential for 100,000 tons by 2020. Instead of shipping all of that to Cargill's North Sea Canal processing plant in Wormer, the Netherlands -- a voyage that takes 24 days -- Cargill hopes to have a Cargill factory in Vietnam by then, processing cocoa liquor, cocoa butter, and cocoa powder for export to growing markets in China and India.

None of that happens without the eager participation of thousands of small growers. One I met last summer was Trinh Van Thanh, a smooth-cheeked 43-year-old with a wife, three daughters, and roughly four acres of land in Baria-Vungtau province, a two-hour drive southeast from Ho Chi Minh City. Five years ago Thanh was growing pepper and coffee and raising pigs, and he was struggling. His pepper trees were afflicted by blight. The yield from his mature coffee trees was declining year by year. He says he was $5,000 in debt.

Thanh planted his first cocoa saplings, as Vietnamese farmers often do, in the shade of his coffee trees. He enrolled in an agricultural extension program in Ho Chi Minh City, where he learned how to build a specialized slow-drip irrigation system based on technology invented on an Israeli kibbutz. When the first crop came in, Thanh made the ambitious choice to ferment and dry the cocoa beans himself. Ultimately, he built more fermentation boxes and drying tables than he needed for his own crop, which meant he could perform those value-adding services for other growers. Soon he wasn't just farming, he was running a collection station. Next he planted a cocoa-tree nursery. Then he launched an irrigation consulting business. (The man gets the concept of a virtuous cycle.) Thanh still sells all his beans to Cargill but maybe not for long. What he really wants to learn how to do next, he told me, is make and sell chocolate.

Thanh's success so far almost defies belief. He says his mini cocoa conglomerate will gross more than $850,000 this year. And if his daughter, who's about to graduate from high school, wants to go to college in America -- and he hopes that she will -- he can easily afford it.

Later in Hanoi, I tell Ngoc all about my visit to Baria-Vungtau province. When does a farmer like Thanh, I ask him, become too much of a capitalist for the Socialist Republic of Vietnam? Ngoc beams. "No limit!" he says. Again in English.

No slowing down

As mighty as Cargill may be, it is not immune to setbacks. In fact, the company's fiscal 2012 is off to a dismal start. Revenues rose 34% in the quarter ended Aug. 31, but earnings were down 66%. That after earnings rose more than 60% in the first quarter of fiscal 2011.

Page blames a perfect storm of unforeseen events: spring flooding in the Midwest (Cargill spent $20 million to prevent the Missouri River from washing out its corn-milling plant in Blair, Neb.); the salmonella outbreak in its turkey plant, which led to a partial shutdown and layoffs ("instead of a business that was making money, we have one absorbing the costs of the recall"); a significant wrong bet on a single, unnamed commodity; a "risk-on, risk-off" market environment that otherwise neutralized Cargill's vaunted trading expertise; and, above all, the global recovery that wasn't. "We underestimated the degree to which the world was gonna back up," says Page.

Remarkably, though, Cargill didn't slow down. The company maintained what Page calls a "big acquisition agenda," completing deals for a Central American poultry and meat processor, a German chocolate company, an Italian feed company, and the grain business of AWB Ltd., formerly the government-owned Australian Wheat Board. (Page says the $1.3 billion AWB purchase fills a hole in Cargill's global grain network: "We're in Russia," says Page, "we're in the Ukraine, we're in Canada, we're in the U.S., we're in Argentina, and we just didn't have as vibrant a footprint there.") Cargill also has a pending $2.1 billion offer for Provimi, a global feed company with 7,000 employees in 26 countries; that deal is expected to close by year-end. Few public companies could be that aggressive after bad results. "People always ask, 'Why is Cargill private?' " says Page. "This is probably one of those moments."

Page may not be under pressure from the family shareholders, but that doesn't mean that he is unworried about the future. The real threat to Cargill's long-term prosperity, Page says, is that forces beyond the company's control will infringe on its freedom to operate across markets. Cargill is clearly concerned with the way the global conversation is bending on food security. "You don't want to end up with policies that are counterproductive to feeding everyone," says Page, "and we don't want to end up with a business model that doesn't have any freedom to operate."

Trust us, he's saying, to feed the world, to keep our food safe, to respect the environment, and, by the way, to not gouge farmers or food shoppers at the supermarket. That's asking a lot. Greg Page is keeping a weather eye out. We'd better do the same.

This article is from the November 7, 2011 issue of Fortune. ![]()