Search News

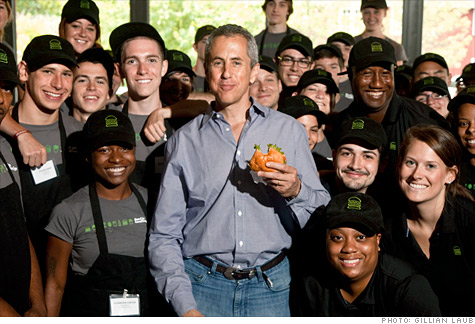

Meyer at a Connecticut Shake Shack: "The burger is only the starting point."

FORTUNE -- Now here's a cultural oxymoron: Danny Meyer, 53, is one of the great American restaurateurs of his generation; his Union Square Hospitality Group owns three of the Zagat Guide's top five fine-dining establishments on the island of Manhattan. When you think of a USHG restaurant, you think of a primo chef, maître d', flowers, and linen tablecloths. So why is Meyer's newest place a burger joint in the middle of suburbia -- just off Exit 19 of Interstate 95 in affluent Westport, Conn., across the street from Sharkey's Cuts for Kids?

Welcome to the first roadside Shake Shack, a potential game changer that could reshape Meyer's entire corporate profile. The inaugural Shack opened seven years ago in a public park in the Flatiron District of Manhattan. (Meyer says the name must have come to him subliminally from watching Grease so many times, since there's an amusement park attraction called Shake Shack in the "You're the One That I Want" dance finale. Good thing that it did, as Meyer had earlier considered the inglorious Custard's First Stand and Dog Park.) All the other nine established U.S. locations -- five in New York City, including the Theater District and Citi Field; two in D.C.; one in Miami; and one at Saratoga Race Course in upstate New York -- are in urban areas or sports venues. There are also two licensed Shacks newly opened in Dubai and Kuwait City.

The suburban Shack is the only one you have to drive to (good luck in the odd-shaped parking lot, which takes patience and daring to navigate); there's even a giant billboard a few miles away on the highway proclaiming the new Black Angus burger in town. The Shack has none of the primary colors of the classic fast-food structure, like the reds and yellows favored by McDonald's (MCD, Fortune 500). Instead, the Westport Shack used muted tan and rust tones. It represents a test of whether the Shack model -- delicious but expensive fast food (plus wine and beer and ShackMeister Ale) combined with thoughtful design and sentient staff -- will appeal in car-centric, affluent, sprawling suburbia. It's a throwback to the kind of place Richie Cunningham and the Fonz used to visit with the gang.

Meyer is pretty earnest when talking about his food joints. He believes restaurants are as much about creating gathering places "to make people happy" as about serving food -- and he sounds much more like an evangelist than a CEO. "The burger is only the starting point," he says. "The magic is how we make people feel." For him, each new Shack has been an experiment: Will folks wait in line outdoors for half an hour at a Mets game? (Okay, it's often better than watching the actual Mets game.) Will they want to eat fancy $9 Double ShackBurgers while watching the ponies run? At each turn so far, the customers have been happy. In the next year, half-a-dozen or so Shacks are set to open: in Philadelphia; Coral Gables, Fla.; the Middle East; and (probably) Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan.

Shake Shacks already constitute "almost a third" of USHG's profits, notwithstanding the $37 Grilled Lamb Chops Scotta Dita at Union Square Cafe. While Meyer won't disclose margins, he smiles when asked about them, and he's commented to others about the "profitability edge" of the Shacks. Meyer knows all about the lure of scale, but is loath to franchise -- he's done so in the Middle East only because he was approached by a successful international franchiser and because his U.S. audience wouldn't see any growing pains halfway around the world. "We can make our victories -- and mistakes -- far away," Meyer says, "and we make a profit that forestalls the day when we need to go out and raise more money."

Meyer has long been ambivalent about growth. It took him four years before he opened a second Shack, he says, "because I didn't intend it to be replicable." His investors continue to be friends and family rather than private equity partners. He's never considered taking USHG public, as other restauratrepreneurs like Steve Ells of Chipotle (CMG) have. As it is, Meyer's managers at the domestic Shacks typically have previously worked at one of his upmarket restaurants, which makes rapid expansion difficult. "It's just not in our DNA," he beefs.

There are surely risks with the suburbs. In Westport there are cheaper, faster offerings every 200 yards along the main drag, and of course there's the famous Super Duper Weenie a couple of towns away. But if the Westport outpost succeeds -- and so far it's been bustling with midday businessmen, after-school teenagers, nighttime families, and weekend couples -- it represents a lucrative prototype. Real estate is cheaper in the suburbs, and you don't have to pick one-off locations like a major league stadium or an urban park. In not so many years, it's a good bet you'll be seeing more Shacks in suburbs around the country. For Danny Meyer, the DNA of the boutique burger may be changing.