Would you eat 2,900-calorie cheese fries?

More cities are requiring restaurants to tell customers how much fat is in that burger. Smart business owners are embracing the trend.

(FORTUNE Small Business) -- Driven by curiosity and customer demand, Marc Geman, CEO of the Spicy Pickle restaurant chain, sent 30 of his top-selling dishes to a testing lab for nutritional analysis. It cost him about $2,500, but he learned everything about each dish, from calories to sodium content, which he then posted on the Spicy Pickle website.

"It was expensive to do, especially for a small business like us," says Geman, whose Denver-based company of six stores and 30 franchises pulled in about $20 million last year. "But I understand that people want to know what they're eating."

Geman is one of a growing number of restaurateurs embracing nutritional disclosure - before the government demands it. To fight an obesity epidemic, dozens of cities and states are considering laws that mandate the posting of nutritional information on menu boards. Officials are targeting chains, because according to a study by market research firm NPD Group, that's where Americans eat 64% of their restaurant meals.

Early adopters include New York City, where a judge recently enforced the hotly-contested law; San Francisco, whose laws take effect in the fall; and King County (Seattle), Wash., which will make changes Jan. 1.

On a national level, U.S. Senator Tom Harkin, D-Iowa, reintroduced legislation in March mandating that chains with at least 20 locations disclose calories, fat, and sodium on menus. While the various laws and proposals differ, most demand that chains with at least 15 restaurants display a calorie count for each dish (including the 2,900-calorie cheese fries at Outback Steakhouse) on or next to menu boards, and post more extensive information elsewhere in the restaurant. Sit-down chains must insert the information into individual menus.

Getting and posting nutritional information isn't cheap, but it's not prohibitively costly either. Beyond the testing fee, Geman estimates that it will cost him and his franchise owners about $5,000 a restaurant to redo the menu boards. But he and other smart owners of small restaurant chains are embracing disclosure as a marketing tool and as a way to discourage officials from outright bans on certain foods and ingredients. (New York City's trans-fat prohibition takes effect in July; Maryland may mimic Chicago's ban on the sale of foie gras.)

These owners also see disclosure as a way to get on the right side of customers. A survey by food services giant Aramark found that 83% of diners want restaurants to make nutritional information available.

"We've seen a jump in orders not only because of the laws but because more restaurants are getting requests from consumers for the nutritional composition," says Erica Bohm, a vice president at Healthy Dining, based in San Diego, which charges $150 for a software-based nutritional analysis of a plate of food. (Lab studies cost $600 to $800.) Bohm estimates that in the past two years requests for software analysis have risen 50%.

Reflecting the view of most industry groups, Chuck Hunt, executive vice president of the New York State Restaurant Association's New York City office, derides the disclosure laws as cumbersome micromanagement of small businesses. And, he adds, "14 years ago the FDA started requiring nutritional information on goods to be eaten in the home. Has that addressed obesity?"

Maybe not, but more consumers are demanding the ability to make informed choices in restaurants. And for both diners and business owners, laws requiring disclosure are far better than the alternative: nanny-state restrictions on what can be served.

For restaurant owners looking to the future, the smart move is to accept the inevitable and try to soften the laws' harsh edges. The National Restaurant Association is advocating more flexibility in sign requirements, and Washington State's restaurant association negotiated raising the minimum chain size from ten to 15 and allowing restaurants to post calories on signs near menu boards.

"Once we got the ordinance changed, I think people's comfort level rose," says Trent House, WRA's director of government affairs.

The Original SoupMan - a 32-location chain based on the Seinfeld Soup Nazi character - is embracing disclosure as a way to differentiate itself in a saturated market.

"We're for it," says president Bob Bertrand, who has paid around $10,000 to have his 40 soups analyzed. "If people see that our nutritionals are better than another fast food, we think that can be good for us." ![]()

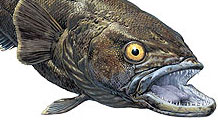

9 forbidden foods: Government agencies have outlawed these forbidden foods, but epicures love them.

Popeyes 'Famous' creator Al Copeland dies

Lunch-hour liposuction

Tips for promoting a new restaurant