The inflation vs. deflation debate

Many economists are worried about prices -- but they disagree about whether prices are going up or down.

|

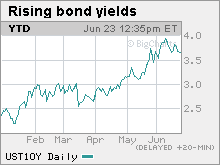

| The increase in the yield for the benchmark U.S. 10-Year Treasury note is a sign to some that the market is starting to worry about inflation. |

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- Should the Federal Reserve be more worried about the threat of inflation on the long-term horizon, or deflation in the short-term?

It's an important question to ask as the Fed's policy-making committee prepares to release a statement about the economy on Wednesday.

Those who fear inflation argue that the recent rise in oil prices, the dollar's loss of value and the recent rise in yields on U.S. Treasurys are all signs that consumers could soon be grappling with higher prices for lots of goods and services.

These economists say the seeds for inflation have been sown by the Fed's extraordinary efforts to keep the economy afloat over the past year.

Many believe the central bank needs to pull back quickly on the various programs it has created to pump cash into the economy, even if the U.S. economy is still struggling. If the Fed doesn't act, it could risk even worse problems down the road -- especially if long-term bond yields and the lending rates tied to them continue to rise.

"There's no doubt that what the Fed is doing today is inflationary," said Brian Wesbury, chief economist at First Trust Portfolios. "The real sign of that is the increase of commodity prices since early this year."

But others argue the economy is still so weak that deflation, or a drop in prices, is the more serious threat. The Consumer Price Index, the government's key inflation measure, posted its largest 12-month drop since 1950 in May.

This year-over-year decline in prices, coupled with rising unemployment and low factory utilization, could be signs that prices are likely to keep falling. And while lower prices might sound like a positive to consumers with budgets stretched to the breaking point, economists are in general agreement that deflation is far more destructive to the economy than inflation.

Businesses unable to make a profit in an environment of declining prices will likely cut production and lay off more workers. That could cause a deflationary spiral. The Great Depression and Japan's so-called Lost Decade of economic stagnation are both well-documented examples of the damage that deflation can cause.

"I think the predominant risk in the next 6 to 12 months is deflation," said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody's Economy.com. "There's excess capacity everywhere. There's vacant real estate across all property types. Unemployment continues to rise. I don't see how businesses can raise prices in this environment."

Zandi said one reason people don't need to fear inflation is because the Fed knows how to fight inflation -- with higher interest rates and tighter money supply.

"But if you get into a deflationary trap, it's very difficult to get out of. Japan is a good case in point," he said.

Rich Yamarone, director of economic research at Argus Research, said he's not concerned about such a trap. But he agreed with Zandi that people shouldn't worry about the prospect of runaway inflation either since the Fed can easily put the brakes on the economy if it has to.

"The next problem coming down the pipe will be inflation, not deflation. I just don't think it'll be happening any time soon," Yamarone said. "And I suspect the guys who control the spigots are on top of this."

Investors looking for clues about how the Fed views the threat of inflation or deflation won't have to wait much longer.

When the Fed wraps up its two day policy meeting Wednesday, it is virtually certain that it will leave its key interest rate near zero. What will be watched more closely is whether its statement has language warning of greater risk from rising or falling prices in the future.

In its last statement, the Fed said it "expects that inflation will remain subdued." It also rang a deflationary warning bell, indicating that "inflation could persist for a time below rates that best foster economic growth and price stability in the longer term."

But the so-called inflation hawks at the Fed have become more vocal since that April meeting about what they see as the growing threat of inflation.

Philadelphia Fed President Charles Plosser argued in a speech last month that unless the Fed soon becomes aggressive in raising rates and disposing of assets it bought during the financial crisis, it could spark the kind of high inflation levels seen in the late 1970s.

Wesbury agrees that the Fed has to be more vigilant about fighting inflation and added that the Fed may soon need to raise rates. He said low inflation today is only a result of oil prices falling from last year's record highs. Core price readings, which strip out food and energy, have remained stubbornly high despite the weak economy.

"In order to fight [inflation], you have to start tightening now," said Wesbury. "By the end of this year it'll be too late to stop the inflation that will be happening in 2011."

But Zandi believes Fed chairman Ben Bernanke and other central bank policymakers that he refers to as "deflation hawks" are still concerned enough about the risk of deflation that he does not think the Fed will rein in its stimulative programs anytime soon just because of long-term inflation fears.

"If they do bow to that view, then I think the risk will rise that we'll have outright deflation," said Zandi. ![]()