Rescuers still fogbound

The feds find more tools for fighting the credit crisis, but what the market wants from Washington is leadership.

|

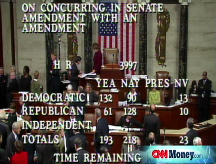

| Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson's proposal to use $700 billion to buy troubled assets from financial institutions was defeated. |

NEW YORK (Fortune) -- Regardless of what happens with the mortgage rescue bill now headed for a vote in the Senate, policymakers haven't run out of tools for hacking away at the edges of the credit crisis.

Unfortunately, it's far from clear that they can be trusted to use their powers wisely, or to any great effect. And if there's any lesson to be learned from the response to the federal interventions of September, it's that the siege mentality in the credit markets won't lift until investors and taxpayers get a sense that Washington is pursuing a grander strategy than writing checks as fast as it can.

"All Washington wants to do is throw money at things," said Robert Lutts, chief investment officer at Cabot Money Management in Salem, Mass. "What we need is for someone to lay out a tangible plan."

The fast-growing financial-meltdown tool chest is getting bigger. The Senate plans late Wednesday to vote on the $700 billion bank rescue plan that the House rejected two days ago. A new provision in the bill would raise the federal bank-deposit insurance limit to $250,000 from $100,000.

Meanwhile, regulators and accounting watchdogs met to further clarify mark-to-market bookkeeping rules. Those rules have been blamed in some circles for intensifying the financial sector's woes by leading companies to write down the value of loans, including some where the payment history was fine.

Those aren't the only options for officials seeking to limit the damage after a month that has seen the failure or nationalization of six major financial firms. The government may soon buy preferred shares in troubled institutions, create tax credits for new home purchases or even cut interest rates again, in the name of helping banks bolster stricken balance sheets.

But simply recycling old tactics or coming up with new ones that have lots of zeros attached to them and saying "trust us" isn't going to restore investor or taxpayer confidence. Washington, says Lutts, must take "a more realistic attitude" than the one behind Henry Paulson's proposal to buy $700 billion worth of troubled assets from financial institutions.

Paulson's plan met with harsh criticism in part because the Treasury secretary proposed his asset purchases - financed with taxpayer dollars - should be exempt from congressional or judicial oversight. But even after legislative leaders killed that notion, the plan they offered up gave little insight into how the money would be spent, or how Paulson would manage the apparent conflicts of interest inherent in buying illiquid assets from cash-strapped firms.

"Any sales at current market value would inflict huge losses on these institutions," wrote Michael Levitt at Hegemony Capital Management in a recent assessment of the bailout plan. "The alternative is for the government to grossly overpay for these assets, which would constitute a disguised capital infusion into these firms that would short-change the American taxpayer."

Yet for all the shortcomings of Paulson's recent efforts, few political leaders have shown any insight into how to fix the nation's economic problems, says Simon Johnson, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

He notes that neither John McCain nor Barack Obama took the opportunity in Friday's presidential debate to say how they would lead the nation out of the credit morass. Both recently advocated raising the FDIC deposit limit, but Johnson calls that a "no-brainer" that leaves countless other questions unresolved.

Among those is the degree to which the candidates would use taxpayer dollars to recapitalize the banking system, which by all accounts is necessary, and where they stand on moves aimed at easing the U.S. consumer spending slowdown - such as new stimulus plans, for instance.

"This is shaping up as the defining issue for the next president and the next Congress," said Johnson, who is also a management professor at MIT. "I don't think they can keep punting on it."

Meanwhile, investors remain frustrated by the failure of policymakers to explain the principles that will guide their intervention in financial markets. After a month that brought the failure of Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual, the nationalization of AIG (AIG, Fortune 500), Fannie Mae (FNM, Fortune 500) and Freddie Mac (FRE, Fortune 500) and the sale of Wachovia (WB, Fortune 500) and Merrill Lynch (MER, Fortune 500), it remains unclear which financial firms will be deemed worthy of government support and which won't.

The feds' waffling on this point - the government stood behind investment bank Bear Stearns to force a sale, while letting a similar firm, Lehman Brothers, collapse without explanation nine months later - will have to be resolved before funds start flowing to financial firms again.

The demise of Lehman and of Washington Mutual, the nation's largest thrift, left creditors nursing hefty losses, and the action in the credit markets of late shows that lenders are determined not to get burned again. If banks keep hoarding their money rather than lending it out, an already struggling economy will inevitably slow even further.

"The current crisis erupted after U.S. policy makers followed a series of seemingly inconsistent policies toward bank failures," wrote Merrill Lynch economist Alex Patelis. "It will end when a line in the sand is drawn between those institutions that are to remain and those that are to disappear."

First, though, someone will have to draw that line. ![]()

-

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More

The retail giant tops the Fortune 500 for the second year in a row. Who else made the list? More -

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More

This group of companies is all about social networking to connect with their customers. More -

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More

The fight over the cholesterol medication is keeping a generic version from hitting the market. More -

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More

Bin Laden may be dead, but the terrorist group he led doesn't need his money. More -

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More

U.S. real estate might be a mess, but in other parts of the world, home prices are jumping. More -

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More

Libya's output is a fraction of global production, but it's crucial to the nation's economy. More -

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More

Once rates start to rise, things could get ugly fast for our neighbors to the north. More