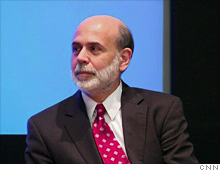

Bernanke denies making threats to BofA

Fed chairman tells Congress he did not threaten to fire Bank of America CEO Ken Lewis and did not order former Treasury secretary Henry Paulson to do so.

|

| Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke told Congress Thursday that he did not issue threats to Bank of America management after the bank considered abandoning its purchase of Merrill Lynch. |

|

| While Bank of America shares have recovered somewhat, many investors still blame the ill-timed purchase of Merrill Lynch for the company's struggling stock price. |

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke denied accusations Thursday that he pressured Bank of America to follow through on its purchase of Merrill Lynch late last year or risk having top management removed.

Testifying the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, the central bank chief maintained that his agency acted with the "highest integrity" in dealing with BofA, countering charges made recently by BofA (BAC, Fortune 500) chief Ken Lewis that Bernanke threatened him with his job when his company considered pulling out of the deal.

"I did not tell Bank of America's management that the Federal Reserve would take action against the board or management," Bernanke said Thursday.

The Fed chief also rejected the notion that he asked former Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson to act on his behalf, a claim made by Lewis earlier this year that came to light during a related investigation on Merrill Lynch bonuses.

Thursday's hearing into Bernanke's role in the controversial deal comes at a time when the administration is looking to expand the Federal Reserve's regulatory powers and just months before his term as chairman expires.

Lawmakers have been eager to determine if the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department overstepped their bounds in pushing through the merger. There have also been questions about whether Bank of America may have used the threat of scuttling the deal as a bargaining chip for additional government assistance.

"We need to get all the facts out on the table before we are in a position to say what happened and when it happened," committee chairman Rep. Edolphus Towns, D-NY, said Thursday.

Testifying before the same committee two weeks ago, Bank of America's Lewis offered up his side of the story, saying he and other company executives were not looking for a handout. Lewis said that BofA approached regulators after discovering the scope of Merrill's losses late last year.

At the time, Bank of America considered invoking the "material adverse change" or MAC clause, of the deal, which would have allowed Bank of America to walk away from the purchase.

But regulators feared that an unraveling of the deal would jeopardize the health of the U.S. financial system and the two firms themselves.

After some behind-the-scenes wrangling, regulators reached an agreement to give BofA $20 billion in aid in January to help them absorb Merrill. That assistance came on top of the $25 billion it received as part of the Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP. BofA also received loss guarantees on $118 billion in assets.

At times Bernanke appeared shaken and frustrated by members' pointed questions about what he did and did not say when the merger appeared as if it might fall apart.

On several occasions Thursday, lawmakers cited a Dec. 20 email by Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond president Jeffrey Lacker. In that email, Lacker recounted a conversation with Bernanke, in which Lacker recalled the Fed chief saying that "management is gone" if Lewis tried to invoke the MAC.

Bernanke maintained that he could not remember the details of that conversation, which made for a heated moment with Rep. Dan Burton, R-Ind.

"One of the things that I learned was in order to keep people from perjuring themselves they couldn't remember anything. Are you sure you can't remember?" asked Burton.

Bernanke clarified Lacker's comments, noting that what he said was that if Bank of America abandoned the deal and later on needed further government assistance as a result, then the firm would have to answer to regulators.

"I think if somebody makes a decision that results in their company failing and being rescued by the government, I think there should be consequences for them," he told lawmakers.

Bernanke also modified his "bargaining chip" remark that was widely cited in a Republican memo prepared for Thursday's hearing. Bernanke noted that at first he believed Lewis was using the MAC threat to gain more assistance. But he said Thursday that further talks with Lewis later led him to believe that the BofA chief was just really uncertain about what to do.

As was the case during Lewis' hearing two weeks ago, members of Congress also seized on the issue of disclosure during Thursday's hearing.

Bernanke and Paulson have been accused of ordering Lewis not to disclose the details of talks with regulators. Others have charged that the two men failed to keep their fellow regulators in the loop, namely the Securities and Exchange Commission and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, regarding what was happening with Bank of America.

Bernanke denied claims that he and Paulson tried to keep details of the negotiations with Bank of America a secret. On Wednesday, Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif, the committee's ranking member, went so far as to call the Fed's actions in the BofA-Merrill deal a "cover-up."

The issue of transparency at the Federal Reserve comes at a critical time. Lawmakers are carefully considering whether to give the agency a broader regulatory reach, one of the key components of the regulatory reform plan announced by President Obama last week.

This has given some lawmakers pause, particularly in light of what happened with Bank of America and Merrill Lynch.

"We can't afford to make the Fed a super regulator, as some have proposed, without also increasing its transparency in meaningful ways," said Rep. Dennis Kucinich, D-Ohio. ![]()