TARP cop: Get tough on banks

Neil Barofsky says a lot could go wrong with bailouts. He wants better disclosure and stronger conflicts rules. Sparks controversy over total cost.

|

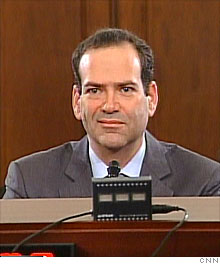

| Neil Barofsky will testify before a House panel Tuesday about stamping out potential fraud from the bailout. |

WASHINGTON (CNNMoney.com) -- The top cop tracking the $700 billion bailout program said Monday that he's concerned federal officials are ignoring his proposals for preventing tax dollars from being wasted or pilfered.

Neil Barofsky, the special inspector general overseeing the Troubled Asset Relief Program, released a 260-page report detailing a long list of concerns about government efforts to prop up hundreds of banks, Wall Street firms and auto companies.

The report criticizes the Treasury Department the most for its unwillingness to adopt some of his recommendations.

Barofsky cites two examples: He wants Treasury to force bailout recipients to keep track of how exactly they are spending TARP funds. He also wants officials to erect a "firewall" to prevent private investment managers -- the kind hired to manage and invest taxpayer dollars -- from taking advantage of insider knowledge.

"Although Treasury has taken some steps towards improving transparency in TARP programs, it has repeatedly failed to adopt recommendations that SIGTARP believes are essential to providing basic transparency and fulfill Treasury's stated commitment to implement TARP 'with the highest degree of accountability and transparency possible,' " the report stated.

Barofsky is set to testify about the report Tuesday morning before a House Oversight panel.

The special IG's office, which was established as part of the TARP program enacted last fall, has also launched 35 criminal and civil investigations into a range of allegations from accounting and securities fraud to insider trading and public corruption, the report said.

Some of Barofsky's investigations have already led to criminal and civil charges against those accused of fraudulently benefiting from the government's bailout program.

Some lawmakers are already squealing about one figure in Barofsky's report, which assigns an eye-popping value of $23.7 trillion as the sum total of dozens of federal programs supporting companies, industries and consumers affected by the economic meltdown.

"Any assessment of the effectiveness or the cost of TARP should be made in the context of these broader efforts," Barofsky is expected to say to the House panel, according to testimony acquired by CNNMoney.com.

The $23.7 trillion number is a "staggering figure," said Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., the ranking minority member of the House Oversight panel.

Yet, the aggregate figure contains programs that the government is no longer on the hook for. For example, it includes $12.9 billion bridge loan to JPMorgan Chase to buy failed investment bank Bear Stearns in March 2008 -- that loan was repaid in full with taxpayers making $4 million in interest.

The aggregate figure also includes bank debt backed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Taxpayers are on the hook if the banks can't make good on the debt, but so far taxpayers haven't lost a dime and have in fact made billions in fees paid to the program, said industry analyst Jaret Seiberg, who generally supports transparency and disclosure of risk.

"You can start raising questions about lots of different components, but that's throwing lighter fluid on an already politically-charged fight to produce nothing of substance," said Seiberg of Concept Capital's Washington Research Group.

A Treasury official on Monday called the $23.7 trillion figure "inflated," saying it ignores fees and interest that regulators collect to compensate taxpayers for taking on risk. The official added that Barofsky's estimate doesn't take into account assets the federal government now owns that "offset the risk" in these programs.

"While quantity and quality of the assets backing all of these programs vary, ignoring that side of these programs misrepresents 'potential exposure' associated with them," the official said.

The report primarily focuses on pressing regulators to adopt suggestions Barofsky has made in previous reports, including asking all bailout recipients to account for their actual use of TARP funds.

Barofsky said he surveyed hundreds of TARP banks several months ago and all of them responded, saying they tended to use their bailout money to lend and to shore up their balance sheets. However, Treasury does not require banks to provide detailed and public reports on how they use the bailout dollars.

The report also pushes for a stronger conflicts walls inside firms that have been hired to pair private dollars with public investments to buy troubled securities from banks in so-called Public-Private Investment Funds.

The government recently announced that it has chosen nine firms to manage the public-private funds. The firms have 12 weeks to raise $500 million each from private investors willing to invest in toxic securities held by banks. Those investments will be matched by the Treasury and supplemented with debt financing from the agency.

Barofsky warns that allowing fund managers to work with taxpayer dollars while also serving other clients could tempt managers to use insider information to benefit other clients.

"The reputational risk that Treasury and the program could face if a PPIF manager should generate massive profits in its non-PPIF funds as a result of an unfair advantage ... justifies the imposition of a wall," the report states.

Treasury officials, in correspondence that Barofsky includes in his report, say they believe they have put enough protections in place to prevent conflicts of interest. They feared that requiring such a wall would deter fund managers from partaking in the program and would also prevent government from getting access to firms' "A-team."

"While using a segregated team to manage the PPIF might reduce the possibility that non-PPIF investors could benefit at the expense of taxpayers, Treasury concluded that such an arrangement is simply not practicable," wrote Herbert Allison, the assistant secretary for financial stability.

The report makes clear that Barofsky's work is just beginning. He plans to release future reports on how bailed-out companies are complying with executive pay caps, whether outside parties influenced regulators in their bailout decisions and the process by which the first nine bailouts were bestowed -- with a focus on Bank of America (BAC, Fortune 500). ![]()