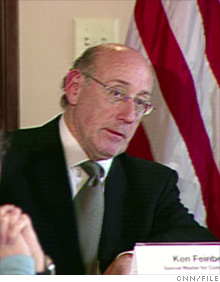

Bailed-out banks: Meet the pay czar

Firms that required multiple interventions, including GM, Citi and AIG, to submit pay plans for top performers to White House overseer Ken Feinberg.

|

| White House pay czar Kenneth Feinberg |

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- Just how much is a rainmaker at a bailed-out bank really worth? Or a senior executive at a recently bankrupt automaker for that matter?

Such questions will soon be a subject of discussion at the White House as the biggest recipients of government aid begin submitting compensation plans for their top 100 employees to the Obama administration's recently appointed pay czar.

Seven companies -- AIG (AIG, Fortune 500), Chrysler, Citigroup (C, Fortune 500), Chrysler Financial, Bank of America (BAC, Fortune 500), General Motors and GMAC -- are due to submit proposed employment contracts for their 25 highest-paid employees Friday. Compensation proposals for the next 75 most compensated employees are due by Oct. 13.

Kenneth Feinberg, the man charged with handling the task, is expected to rule on the first set of pay plans within the next 60 days. That information is due to be made public by Treasury sometime after, although any announcement may not include details of pay packages for individual employees.

Feinberg, a Washington attorney who first entered the public spotlight after overseeing compensation payments to September 11 victims, has already met with the seven firms to discuss some of the employee payment plans.

However, details of those talks have remained mostly under wraps, although there have been indications of a lot of back-and-forth between Feinberg's office and the institutions.

Citigroup, for example, has been working hard to claim that its agreement to pay star energy trader Andrew Hall $100 million this year is beyond Feinberg's authority, according to recent news reports.

Feinberg's authority, while broad enough to approve or deny proposed employment contracts, is more limited on bonuses and other retention awards promised before Feb. 17 of this year. Citigroup is claiming that Hall's compensation package is protected since his contract was signed before the law creating the compensation review program was established, according to the New York Times.

Thorny problems: Resolving the issue of Hall's pay would certainly clear a major hurdle for both Citigroup and Feinberg, who effectively serves as an adviser to the Treasury Department.

But experts contend that making determinations on the other 699 employees at these seven firms could very well be a very messy process, particularly as it relates to those workers at AIG, Citigroup and Bank of America.

Imposing too many restrictions could prompt more top performers to flee Citigroup and Bank of America, hampering the firms' ability to attract talent.

Both banks have already experienced a loss of talent in recent months, both to foreign firms such as Deutsche Bank and competitors such as JPMorgan Chase (JPM, Fortune 500) that are no longer beholden to government.

At the same time, the issue of excessive pay remains a rallying cry for lawmakers and taxpayers alike, who are still incensed over bonuses paid out to AIG executives earlier this year.

"It is a bit of a balancing act," said Claudia Allen, a partner at law firm Neal Gerber & Eisenberg and the chairwoman of the firm's corporate governance practice. "In some ways, how he deals with compensation will be a reflection of what the Treasury and the [Obama] administration finds to be appropriate or acceptable."

What's appropriate?: What the White House has offered so far in terms of what is proper and what isn't, has been limited.

When it outlined its pay restrictions for banks and other firms that got money under the Troubled Asset Relief Program in June, it decreed that any company that got help this year must limit bonuses for senior executives and other highly-paid employees to one-third of their total compensation.

At the same time, it absolved those employees making less than $500,000 in total annual compensation at those firms that were bailed out more than once, saying they would not be subject to scrutiny.

But that still leaves Feinberg's office with the difficult task of determining what is an appropriate mix of bonus, salary and deferred payments such as restricted stock that rise and fall alongside the firm's overall health, noted James Reda, a managing director of the compensation consultancy James F. Reda & Associates.

Critics have charged that banks, in particular, relied too heavily on short-term rewards such as bonuses in the years leading up to the crisis. That ultimately prompted employees to benefit from risky bets, such as those on the U.S. housing market, without suffering the consequences when the market unraveled years later.

Already, many financial firms have been placing greater emphasis on salary and other forms of restricted awards amid recent scrutiny from lawmakers and taxpayers alike.

But with the government taking a hard look at compensation, bailed-out firms may have little choice than to push even further on that front. That push could include instituting so-called "clawback" provisions to reclaim pay from some executives, as well as more stock-based compensation or even caps on bonuses.

"There are not many other ways to do it," said Reda. ![]()