Banks win round 1 in consumer fight

Top Democrats drop provision to let proposed Consumer Financial Protection Agency establish 'plain vanilla' products. Business says thanks but still wants bill dead.

|

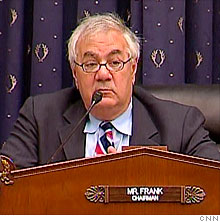

| Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass., releases a memo that details changes to the consumer agency. |

WASHINGTON (CNNMoney.com) -- This summer, when Obama administration officials talked about overhauling financial regulation, they threw around a catchy phrase sure to appeal to consumers: "Plain vanilla" mortgages and credit cards.

"Plain vanilla" was used to illustrate the powers of a proposed new consumer agency. The agency could set basic standards -- like one-page, easy-to-understand applications for 30-year-fixed mortgages.

Now, the so-called Consumer Financial Protection Agency won't get that power, according to a memo on the agency released by House Financial Services Chairman Barney Frank.

The memo also says that some key providers of financial services, such as consumer reporting agencies, real estate brokers and auto dealers, would not be subject to the new agency's oversight.

Although the final bill language has yet to be released, experts on both sides of the fight agree the memo signals that top Democrats have made concessions to smooth passage of the most controversial yet symbolic part of regulatory reform.

And so far, the Obama administration appears to be OK with the changes.

"There's nothing in there that troubles me significantly," said Secretary Tim Geithner during a Wednesday House hearing. "I think the chairman's proposals are a pragmatic helpful way to make sure you have a better balance of choice but protection."

Several advocates of the consumer agency said they weren't surprised to see that the "plain vanilla" provision got yanked, because it had become the loudest complaint by the financial services sector. Banks argued that such a provision would hurt their ability to provide consumers with financial product choices.

"'Plain vanilla' was just such a no-go for the industry, that was loud and clear," said Melissa Koide of the New America Foundation, a left-leaning Washington policy group. "It's disappointing it's coming out, because there was some middle ground on the issue."

Still, some experts said the loss of the "plain vanilla" mandate is not a significant blow to the proposed agency, which would still be able to "promote the use of safer products," said Ed Mierzwinski, the consumer program director for U.S. Public Interest Research Group.

More troubling is that the House appears intent on exempting from new regulation some big players that provide auto loans and reports on consumers' credit-worthiness, Koide said.

The Frank memo also makes it clear that lawmakers don't want to regulate merchants and retailers who give their customers credit or layaway plans. An ad campaign paid by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce opposing the proposal featured a butcher and baker concerned about its possible impact on their businesses.

The consumer agency would still have a mandate "to set strong rules" for banks and non-banks, the memo said. And states would still be allowed to pass their own laws aimed at protecting financial consumers, even if such laws are tougher those set by federal regulators.

Even after the changes, the financial services industry still isn't on board.

Statements from the American Bankers Association, the Financial Services Roundtable and the Chamber of Commerce acknowledged the committee's efforts to address their concerns, while making it clear they still want to kill the bill.

They all oppose any agency that could set new rules without considering whether those rules threaten the safety and soundness of financial institutions.

"We agree with the CFP, just not the A," said Scott Talbott, chief lobbyist for the Financial Services Roundtable.

At a hearing on Wednesday, Frank made it clear that he's not interested in the alternative embraced by the financial services sector: Beefing up existing consumer protection departments inside banking regulators.

"It is simply not the case that they've paid much attention to [consumer issues]," Frank said. "They never cared about consumer affairs. It's not that they are bad people, it is a fact that safety and soundness is their main concern. They regard consumer affairs as kind of a nuisance."

Frank said he plans to ask federal regulators to tally their record on consumer affairs activity. "It's not very impressive," he said. ![]()