Berkshire Hathaway for $68? Sweet!

Stock splits don't change the value of a company. But a lower share price for Warren Buffett's firm (and other triple-digit stocks) could attract more investors.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- I don't know about you, but I don't have a spare $101,900 stuffed under my couch cushions to buy an "A" share of Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway. I probably could scrounge together $3,395 for one "B" share, but I would rather not.

However, the possibility of spending $1,000 to purchase 15 so-called "Baby Berkshire" B shares is somewhat intriguing. And soon, you and I will have the chance to do so.

When Buffett announced earlier this week that Berkshire (BRKA, Fortune 500) was buying railroad Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNI, Fortune 500) for a mix of cash and stock, Berkshire also announced a 50-1 stock split of the company's B shares.

That means that once the split is complete, current shareholders of the B stock (BRKB) will receive 50 shares for each 1 they own now. As a result, the cost of one Baby Berkshire share will be 1/50th the current price -- that works out to $67.90 a share based on Thursday's closing price.

This is very interesting considering that Buffett has been famously against the idea of stock splits in the past. Keep in mind, a stock split is really nothing more than a cosmetic change to a company. It's all about altering the perception of whether a stock is expensive or cheap, not its true value.

If you own 10 Berkshire B shares, for example, your investment is worth $33,950 using Thursday's price. If the 50-1 split took place Friday morning, you'd simply own 500 shares that each have a price of $67.90 -- still $33,950.

So why did Buffett decide to split Berkshire's B stock? Well, it's not because he's had a change of heart and now wants to make Berkshire more affordable to the masses.

In an interview with my colleague Poppy Harlow on Tuesday, Buffett said that the reason for the split was to avoid socking smaller shareholders of Burlington with a big tax hit once they received Berkshire stock.

He added that the fact that more individual investors will be able to buy Berkshire B shares was "a consequence" of the split, not the motivation for it.

Now I get the rationale behind not splitting a company's stock. Reducing the per share price could encourage more fickle, short-term traders to buy the stock. Buffett is obviously more interested in attracting long-term investors.

Still, I'd like to think that there are some average investors out there who will take advantage of the lower-priced shares and hold them for a long time as opposed to buying at $70 and quickly dumping at say, $100.

What's more, several academic studies have found that companies that split their stocks tend to outperform the broader market. It makes sense when you think about it.

If a stock is trading at a high enough price that management is considering a split, good news is likely the reason the stock soared in the first place.

In other words, quality companies are more likely to split their stocks than companies that are struggling and being punished by the market as a result.

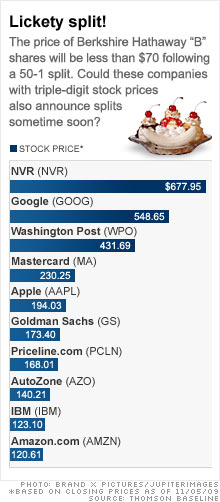

So now that Berkshire has finally decided to split at least one of its classes of stock -- even if it was only to facilitate a takeover -- I am wondering if other companies with sky-high prices might soon follow Buffett's lead.

In the technology sector, there are several companies with stocks trading in the rarified air of triple-digit prices, including Apple (AAPL, Fortune 500), Amazon.com (AMZN, Fortune 500), IBM (IBM, Fortune 500), Priceline.com (PCLN) and Google (GOOG, Fortune 500).

I don't think it's out of the question for four of these five to announce a split in the not so distant future. Apple has split its stock in the past. Its last one took place in 2005. And at that time, Apple was merely trading at a split-adjusted price of about $90. It's nearly $200 now.

IBM has done numerous stock splits throughout its long history, but its most recent one was ten years ago. Amazon.com -- which actually split its stock three times between June 1998 and September 1999 but hasn't done so since -- seems ripe for a split now that its stock as at an all-time high.

And in a delicious bit of irony, Priceline.com seems ready for a split even though the only time the company has conducted a split in the past was when it needed to do what's known as a reverse split.

In reverse splits, companies reduce the number of shares outstanding in order to boost the per share price. That's usually a sign of desperation from companies struggling to meet an exchange's listing requirements or attract big institutional investors.

Priceline.com did a reverse split back in 2003 when its stock price was in the single digits. But the stock has come roaring back in recent years as the company has proven itself to be not just a survivor of the dot-com bust, but a profitable industry leader.

Then there's Google. The company has so far shown no willingness to split its stock. And there's a good argument to be made that this hasn't hurt the company.

Google went public at $85 a share five years ago -- an extremely high offering price for an IPO. The stock went as high as $747 in late 2007 (just before the recession began) and now trades for about $550. So sticker shock hasn't scared investors away.

Google famously quoted Warren Buffett in its filings with the SEC when it first planned to go public. But now that Berkshire has announced the previously unthinkable and is going to split the B shares, maybe Google will once again find itself inspired by the Oracle of Omaha.

Talkback: Are you interested in buying the more affordable Berkshire Hathaway shares after they split? Are there other stocks you would like to see split? Share your comments below. ![]()