How to lose money fast: Open a business

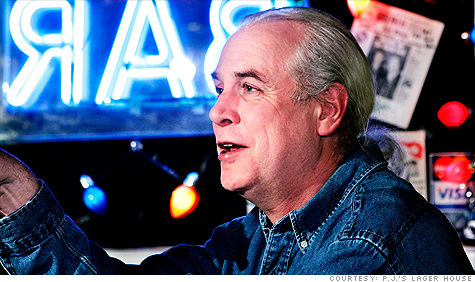

DETROIT (CNNMoney.com) -- P.J. Ryder knew making the rock club he bought a financial success was going to be a challenge. But he didn't anticipate that two years after opening, P.J.'s Lager House would still not be profitable.

"I had hoped it would happen after a year, but people told me not to expect anything for a while," says Ryder, 55.

Being your own boss sounds great -- until the bills start rolling in. At P.J.'s, that means $3,000 a month for rent. Another $7,000 for booze. Repairs and insurance typically eat up more than $1,000. Just keeping the lights on and the water running is $700.

The magic number is $26,370. That's the average monthly cost of keeping the club open. You have to sell a lot of PBR ($1 a can on Monday nights) to hit that target.

After two years of investment, Ryder is finally reaching the payoff point. "I can see light at the end of the tunnel," he says. Located in Corktown, just a few blocks west of downtown in one of Detroit's oldest neighborhoods, the bar has been steadily building up its sales and closing the monthly budget gap. Ryder thinks it's finally about to cross over into the black: "I can see where it is beginning to smooth out."

In a city with an unemployment rate hovering near 30%, entrepreneurship is an alluring career option. Can't find a job in your field? Create one.

But as Ryder's experience illustrates, it's not for the squeamish. Ryder has sunk hundreds of thousands of dollars and two years of round-the-clock labor into building his dream club. He continues to work for free.

And it's not his first business venture. After graduating from the University of Michigan, Ryder joined with a few partners to buy and run a record store in Ann Arbor for 15 years. He moved to Detroit after marrying Donna Terek, a Detroit News photographer, and started a new career selling houses in the city.

Ten years later, he realized he was tired of the erratic hours and increasingly shady mortgage deals. So he quit and, with a partner, decided to buy a bar that would feature live music.

It took eight months to find the right spot: a bar called the Lager House. The pair bought the 1914 building on a land contract for $300,000 and paid $50,000 for the business. "The owners' business volume had been slipping and the building was falling apart," Ryder says. But he was thrilled with the purchase, and closed the deal in October 2007.

Ryder funded the down payment with $100,000 he inherited after the death of his father and a $50,000 home equity loan. But before investing any money in the deal, his partner bowed out. "It threw me for a loop, but I had no choice and moved ahead," Ryder says.

Ryder called in experts to help him structure his new business. An attorney set up the bar as an S-corp named Grootka Inc.; the building is owned by Essoterek LLC. Keeping the two projects separate protects both in the event of a lawsuit against one or the other.

He also turned for advice to his neighbor Gary Shields, an adjunct professor in Wayne State University's School of Business, Management and Information Sciences. Shields, who owns a test preparation company for graduate students, teaches an elective on entrepreneurial management. Ryder visited the class to talk about his new venture, and students wrote a business plan.

The exercise illustrated some of the misconceptions people hold about entertainment businesses. The students expected that the bands would bring in buckets of money. "If the business plan had worked out, P.J. would be a millionaire," Shields says.

Not quite. To get working capital for the bar, Ryder tapped out his credit cards. The interest charges climbed up to $600 a month, prompting him to borrow from his Roth IRAs to pay off the credit card debt.

"The first year, I also was taking money out of our personal savings accounts every two to three months," Ryder says. He estimates that he eventually withdrew $30,000. "I had a lot of skin in the game."

He has not yet been able to replenish the IRAs or the savings account.

Any cash the bar took in during the early days went toward paying down the land contract and repairing the building. Ryder replaced the air conditioning and bought a new compressor. He fixed up the roof, floors, ceiling and basement, and revamped the bar top to add dozens of colorful guitar picks covered with lacquer.

To boost the business's revenue, Ryder renovated and rented out the two apartments above the club. "The way this place is working, the landlord business may be more profitable than the bar," says Erik Melander, Ryder's accountant.

He isn't kidding. From January to October of this year, the bar -- Grootka -- had an average monthly income of $25,000 and expenses of $26,370.

First there's the $3,000 rent the bar pays to its landlord, Essoterek. Beverages cost $7,000 and music runs another $5,000, including fees for a soundman and doorman. Bands are paid 90% of the cover charge, which averages $5. When there is no cover, bands get 20% of the bar sales -- 25% if they bring in a large crowd.

Other monthly overhead expenses include $1,300 for property tax, repairs and insurance; $800 for advertising; $1,500 for sales tax; $500 for credit card fees and related expenses; $700 for utilities; $170 for legal fees and $700 for accounting services. Salaries for the bar's three full-time employees, plus a few part-timers, add up to $4,000.

Toss in another $1,700 for ancillary expenses, and you get a bar that's about $1,000 short of turning a profit.

Sales fluctuate month to month. Summer is the slow season, but business is so brisk on the day of Detroit's St. Patrick's Day parade -- which runs past the bar -- that it counts as a 13th month of income. The club also booms when the Detroit Tigers play their home opener.

"The previous owners had gross annual sales of $200,000. We did $220,000 in the first calendar year and are projecting $300,000 this year," Ryder says.

During the same timeframe, the building -- Essoterek -- produced monthly income of $3,800, from the rent paid to it by the bar and a tenant who has rented out both apartments. Essoterek's monthly expenses include $1,200 for maintenance and repair bills, $500 for utilities, $120 toward new carpeting, $1,300 to pay off the land contract and interest, and $140 in accounting, legal and insurance fees. With bills totaling $3,260, that leaves Essoterek clearing a monthly profit just shy of $600.

What's kept Ryder afloat through two unprofitable years is the financial cushion of his wife's steady job and benefits. But he went in knowing that launching a business would be rough, and he hasn't regretted it for a moment. "If I were a woe-is-me person, I would have a hard time in this business," he says.

He works 60 to 70 hours a week, and often stays at the bar until 2 a.m. With a reliable staff now in place, he's finally able to take time off every so often, but the bar business isn't one for hands-off owners: "If I need to be at the business until 3 a.m., I'm there. If I need to be back at 8 a.m., I'm there."

Melander quips that if Ryder would stop investing in the business, he might make more money. But Ryder clearly takes pride in the appearance of his club. He's just started installing a kitchen in back of the performance space. He plans to rent the area to a cook, to operate an independent business feeding the bar's customers.

Launching P.J.'s Lager House has been an expensive venture, but Ryder is thrilled he's had the opportunity to chase it. Not many big cities allow an entrepreneur without millions of dollars to buy a building so close to downtown and build a business, he points out. Other small businesses are slowly populating Corktown, bringing new entrepreneurs into the area.

Ryder loves having neighbors. "I hope over time it will meet a critical mass," he says. ![]()