Search News

Stanford's Terry Moe

FORTUNE -- What are the most reviled institutions in America? Next to big banks and oil companies, it's probably the teachers unions. The National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers have more than 4 million members between them and spend tens of millions on lobbying and other political activities every year. Legislators in both parties are moving to reduce their bargaining power and limit their pension booty. Last year's ballyhooed documentary Waiting for Superman makes teachers union leaders look like Al Capone with a picket sign. Parents demand to know why Billy and Susie's lousy first-grade teacher gets lifelong job protection when assembly-line workers are laid off by the thousands.

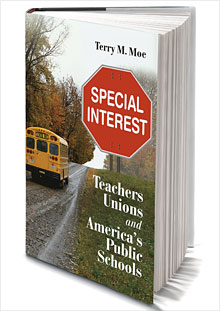

Roiling debates in state capitals across the land demonstrate a backlash against the unions. But a new book by Terry Moe argues that it's technology, not politics, that will be their undoing. Moe is a political science professor at Stanford and has long been a leading advocate for charter schools and vouchers. Special Interest is in part a solid history of the rise of the unions not so long ago -- in the 1960s and '70s. But the book's analysis of sweeping trends is what's most compelling. Moe says legislative reforms like No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top "are small things by comparison, and they can be blocked." By contrast, "education technology is a tsunami that is only now beginning to swell." Unions "can't stop it, although they will try."

Moe, 61, is talking about the web, fast connections, improved screens, and a growing consensus that there are truly superstar teachers. He says cheap technology will massively substitute for expensive labor. Geography and economic disparity will become irrelevant for teaching -- and that means teachers "no longer need to be concentrated in districts." These transformative, entrepreneurial changes -- a "historical accident, a force from the outside" -- will "undermine the very foundations of union power." Since teachers can be anywhere -- and there will be fewer of them -- it'll be harder for unions to organize.

Imagine your high-schooler learning American history from a teacher in Milwaukee and calculus from someone in Boston. Interactive software will facilitate tailored instruction, but it won't require a human in front of a classroom for every 23.138 students. States will still oversee such virtual learning. And even with online learning, students will still attend physical schools.

It's not all fantasy. That "hybrid" approach is already in place. Pilot curriculums in different cities, like the Rocketship program in San Jose that Moe discusses, are experimenting with computerized individualized instruction.

Moe's predictions and prescriptions may or may not happen. Nobody knows whether depersonalized learning works in the long run, notwithstanding a generation of kids facile with keyboards. The notion that a middle-school boy in front of a computer is going to be productive might make some parents (like me) chortle. And the teachers unions themselves have already lodged challenges, political and judicial, to virtual learning. Even so, Moe's book offers hope that the public education system may yet be changing. ![]()

| Latest Report | Next Update |

|---|---|

| Home prices | Aug 28 |

| Consumer confidence | Aug 28 |

| GDP | Aug 29 |

| Manufacturing (ISM) | Sept 4 |

| Jobs | Sept 7 |

| Inflation (CPI) | Sept 14 |

| Retail sales | Sept 14 |