Making the (tough) case for free markets

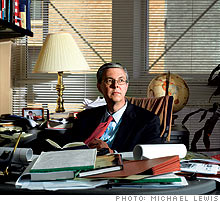

Deregulation suddenly looks like a mistake. But Brink Lindsey, one of Washington's sharpest market advocates, says liberals wouldn't really want a return to the past.

(Money Magazine) -- After three decades of dominating the political conversation, free-market thinking is out of style. The new conventional wisdom: It's time to go back to the pre-Reagan era of strong government and secure jobs.

But Brink Lindsey of the libertarian Cato Institute (a think tank that provided a lot of the intellectual ammunition for deregulation) wants you to know that the good old days weren't as good as you might think.

He's not just talking dollars-and-cents economics. Lindsey says it's no coincidence that markets blossomed alongside social freedoms we now take for granted. Contributing writer David Futrelle talked to Lindsey about all that - and about whether his side is really to blame for the mess we're in now.

The financial crisis has been widely blamed on government putting too much faith in the market. Is it a tough time to be a free-market advocate?

We're definitely on our heels at the moment. But the idea that this crisis shows that government is smarter than markets is wrong. Clearly there were private-sector failures. But to the extent that public policy was weighing in, it was weighing in as hard as it could in favor of ever-broader home ownership.

What's your take on the new financial regulations President Obama has proposed?

Generally, the Obama approach is based on the predictable - but mistaken - premise that the crisis occurred because of insufficient regulation, so we need to give regulators new powers. But regulators, using existing authority, could have done something about the steady deterioration in mortgage underwriting standards, and they chose not to. They could have done something about the use of securitization to get around capital requirements, but they chose not to. The idea that the government can prick these bubbles in their infancy is a fantasy. When bubble psychology takes over, it affects everyone - and that includes the regulators.

Are there any steps you think would help?

Eliminating the tax deduction for corporate interest payments is worth considering. Excessive leverage was obviously a major contributor to the financial crisis, and our current tax system pushes in that direction by favoring borrowing over issuing stock.

You say we're in the grip of "nostalgianomics." What does that mean?

Both liberals and conservatives pine for the 1950s. The only difference is that the left wants to work there, and the right wants to go home there. The left looks back fondly to the days of a heavily unionized workforce, to a time when there was a predictability in economic life and people could look forward to working 50 years on the line. On the right, meanwhile, there's nostalgia for the Ozzie and Harriet family.

Given how insecure everyone feels now, isn't some of that nostalgia justified?

Sure. During the golden 25 years from the end of World War II to the early 1970s, we saw consistently high growth in per capita income. Everybody was doing well, and the people at the bottom gained more than those at the top, so there was declining inequality. Contrast that with the boom from the early '80s until last year. The economy did well in this period, but we never approached the high productivity growth of the postwar years, with the exception of the late '90s and the early 2000s. Meanwhile, we've seen income inequality grow in recent years. The people at the top were doing much, much better, but the lot of the rest of us was improving much more slowly.

Can't we go back to high wages for all?

The successes of the postwar years were driven by specific historical circumstances. There was pent-up demand from the Depression and war and an acceleration of technological change because of the war. The poor South and the underdeveloped West had a huge burst of growth as they caught up with the rest of the country. Meanwhile, competition from abroad was much meeker than it is today. Europe and Japan were smoking ruins. We prospered in spite of, not because of, the specific policies that the left is nostalgic about.

You say the success of women is one reason America looks more unequal. How so?

As women have gone into the workforce, we've seen their wages starting to catch up with those of men. People increasingly marry those with a similar background, so high-skilled men marry high-skilled women and double up on their income gains. And so the unintended consequence of the feminist revolution has been to expand the gap between the skilled and the unskilled and to exacerbate income inequality between households.

You've also argued that going back to a 1950s economy would mean going back to a society most liberals would hate.

In the '40s and '50s there was a much bigger emphasis on an Organization Man, and it was unseemly to go chasing around in the marketplace for the highest dollar. There was a culture of promoting from within in corporations. And it was tough to break through. So the good old days were good if you were a white guy. Not so good if you were a woman. Not so good if you were black, and not so good if you wanted to immigrate to the United States to make a better life for yourself. ![]()