Search News

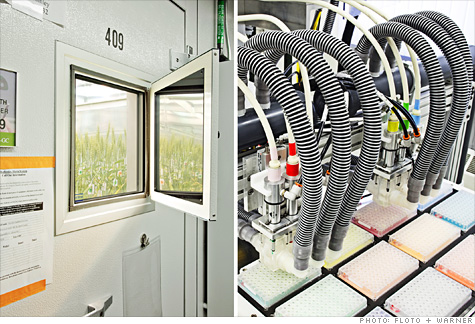

(Fortune) -- "It's fascinatin' because we're in uncharted terri-tree," says the genial, Scottish, entertainingly named Hugh Grant, 52. He is the CEO of Monsanto, possibly America's most feared corporation. Monsanto dominates the agricultural biotechnology industry, whose audacious mission is to transform the genetic composition of the world's food supply. More than 80% of the soybeans and cotton harvested in this country now have at least one patented Monsanto gene in them, as does more than 70% of the field corn.

Monsanto (MON, Fortune 500) is the company best known, depending on which documentary film one has seen, for feeding Frankenfoods to our children, courting ecological catastrophe, or bringing ruinous patent suits against struggling family farmers.

On the other hand, those who don't vilify Monsanto tend to rhapsodize about it, or at least about its mission. In a world on pace to spawn 9.1 billion mouths to feed by 2050, the black magic of ag-biotech offers the only apparent prospect of salvation: crops that will be, it is promised, ever more resistant to insects, disease, and climatic stress; that will require ever less water, fertilizer, and pesticide; and that will bring forth ever more abundant, hardy, and nutritious harvests.

Whichever school of thought one subscribes to, there is now a fresh reason to fear Monsanto. It relates to the "uncharted territory" Monsanto's Grant is alluding to through his rolled r's and glottal stops. The most important genetic trait ever engineered -- the Monsanto herbicide-tolerance gene known as Roundup Ready -- is about to come off patent and, in a testament to just how young this entire business sector is, that's never happened before.

Monsanto competitor DuPont (DD, Fortune 500) claims, and federal and state antitrust regulators are probing whether, Monsanto is using abusive patent license provisions and other tricks of the trade to hobble the development of both the generic versions of Roundup Ready and a patented rival DuPont product, known as Optimum GAT. DuPont sells genetically modified seeds through its subsidiary Pioneer Hi-Bred International of Johnston, Iowa. DuPont/Pioneer asserts that Monsanto, if successful in postponing the availability of those competing products, will force farmers to switch to Monsanto's own second-generation offering, Roundup Ready 2 Yield, whose patents won't run out till 2020. Roundup Ready 2 currently costs about 40% more than its predecessor.

"The cost to farmers and consumers if Monsanto succeeds will be in the billions of dollars," asserts David Boies, DuPont's lead outside lawyer and perhaps the most sought-after American trial lawyer of his generation. "But the worst cost," Boies says, "will be the restrictions on innovation and the restraints on yields that prevent American growers from being more competitive around the world and keep us from feeding more people with less resources."

Monsanto protests that DuPont's contentions are nonsense and that its rival is cynically manipulating both public opinion and the antitrust regulators in an effort to gain leverage in a mundane business dispute. DuPont's real problem, Monsanto maintains, is that it suffered a setback in its product pipeline: A key DuPont genetic trait simply didn't work as well as hoped. Now DuPont needs Monsanto's Roundup Ready 1 to fix its problem, and it's refusing to pay Monsanto a fair licensing fee.

"I expect payment inside my patent life," says Grant, who claims that the dispute is really that simple. "The story takes longer to tell than it really should."

At the core of this controversy is something lawyers refer to as the "patent bargain." In the Constitution, the Founding Fathers gave Congress the power "to promote the progress of science and useful arts" by rewarding inventors with a lawful monopoly on the sales of their innovations for a limited period -- currently set at 20 years from the day the patent application is filed. In exchange, the inventor must teach the world how to duplicate his invention. At the end of the patent term, this know-how enters the public domain.

As Roundup Ready nears the end of its patent life -- for soybeans, that will happen in 2014 -- the concern is that Monsanto could, by forbidding rivals from even starting the multiyear process of developing, testing, and internationally registering generic versions of Roundup Ready until its patent term has expired, effectively extend its monopoly an extra five to seven years, if not longer.

The controversy springs from a legislative void. While the pharmaceutical industry has the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 to tell its players exactly how to transition seamlessly from patent monopolies to generic competition, agricultural biotech has no equivalent.

Far more is at stake here than a simple attempt to finagle a few extra years of patent protection for a successful product -- a common enough drill in the pharmaceutical industry. The stakes are higher because this industry differs from the drug business in one crucial respect. With pharmaceuticals, a patient with two medical needs can purchase one company's patented pill for his first condition and another firm's patented gelcap for the other.

In the world of ag-biotech, in contrast, a consumer lacks that freedom. He is constrained by the fact that a plant can grow from only one seed. If a farmer wants his crop to contain more than one patented genetic trait -- say, soybeans with the Roundup Ready trait and an insect-resistance gene engineered by a competitor like DuPont, Bayer (BAYRY), Syngenta (SYT), Dow AgroSciences (DOW, Fortune 500), or BASF -- the traits must be bred into a single seed, that is, "stacked" on top of each other.

Many farmers regard the Roundup Ready trait as so crucial that they will not buy other genetically engineered traits unless those are stacked in seeds that already contain Roundup Ready, a gene that makes crops immune to the most widely used weed killer. Trait developers and seed breeders, in turn, can't stack a trait on top of Roundup Ready unless Monsanto gives them permission to do so in a patent license.

In the view of DuPont and other alarmed observers, this situation makes Monsanto an industry gatekeeper, capable of deciding which new genetically modified traits can be introduced and which cannot. Put another way, Roundup Ready has become a monopoly platform product, much like what the Microsoft Windows operating system became in the market for personal computer software in the late 1990s.

The parallels are not lost on DuPont's longtime outside counsel Boies, chairman of Boies Schiller & Flexner, who was the Justice Department's lead trial counsel in its antitrust case against Microsoft. He argues that Monsanto's stacking restrictions are actually more objectionable than the conduct that got Microsoft (MSFT, Fortune 500) into trouble 15 years ago. "Microsoft's actions were designed to inhibit the stacking of the Netscape browser on the Microsoft Windows operating system," says Boies. "Here, you have outright prohibition of stacking genetic traits on top of Monsanto's Roundup Ready trait."

Monsanto officials charge that Boies's arguments are part of a DuPont-instigated campaign of "noise" and "fabrication." Monsanto routinely licenses stacking rights to trait developers, they say, pointing to at least nine commercial seed products on the market today in which non-Monsanto traits (including one of DuPont's) are stacked atop a Monsanto trait. The problem, they say, is that while DuPont licensed the right to stack most genes on top of Roundup Ready, it's now stacking a gene that falls outside its license. That's a stacking right "they never paid for," says Grant. "That's the gist of this thing."

Read the full story: Monsanto's seeds of discord ![]()

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |