Regional banks line up for government $

Several top banks have said they are interested in a piece of the $125B set aside for them. Lousy quarterly numbers may push other banks to ask for help.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com -- When the U.S. government starts cutting checks to troubled financial institutions, expect many of the nation's struggling regional banks to be first in line.

In recent weeks, federal regulators have employed plenty of firepower to get banks lending again - most notably last week's proposal to inject $250 billion directly into financial firms.

Half of that amount has already been set aside for nine of the nation's leading financial institutions -- including Citigroup (C, Fortune 500), Bank of America (BAC, Fortune 500) and Goldman Sachs (GS, Fortune 500). Now, regulators are dangling the remaining $125 billion in front of thousands of other banks and thrifts nationwide.

So far, the program has garnered interest from "banks of all sizes," Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson indicated Monday.

But with most community-level institutions well capitalized and the nation's biggest banks already having thrown their hat in the ring, experts are betting that regional banks will be clamoring most loudly for government funds.

Top executives at a handful of companies including PNC (PNC, Fortune 500) and BB&T Corp (BBT, Fortune 500)., have already said they were taking a close look at the program.

On Tuesday, Birmingham, Ala.-based Regions Financial (RF, Fortune 500) said after reporting that its third-quarter earnings fell 80% from a year ago that it planned to apply for government capital before the Nov. 14 deadline.

Cleveland-based banks National City (NCC, Fortune 500) and KeyCorp. (KEY, Fortune 500) may very well be likely candidates for a government investment after the duo each reported a quarterly loss Tuesday as a result of rising loan losses.

Fifth Third Bancorp (FITB, Fortune 500), which swung to a loss Tuesday as well, also indicated it was weighing a government capital injection. The Cincinnati-based bank had previously said it was planning to sell some of its non-core assets to raise cash.

"I would think all three will say 'We want some additional capital given the uncertainty in the economic environment', " said Fred Cummings, a former bank analyst and president of the hedge fund Elizabeth Park Capital Management in Beachwood, Ohio, about the need for National City, KeyCorp and Fifth Third to seek federal help.

To be sure, there has been some skepticism about the government plan, which was first announced last week.

Many companies are still waiting for further details about the plan before signing up, according to industry groups. At the same time, experts have indicated that banks are nervous about the stigma associated with having the government taking an ownership stake.

In exchange for capital, banks must give up a stake to the U.S. government, but they also have to agree to pay a dividend on those shares and keep pay packages of their top executives in check.

But analysts largely agree that the government investment would be a cheap way for banks to raise capital at a time when it has become so precious for financial institutions.

"It is a reasonably priced piece of capital that in this environment some banks would not be able to find," said Gerard Cassidy, managing director of bank equity research at RBC Capital Markets. "If you think you're going to need it, you might as well take it."

While Paulson stressed this week that there is plenty of money to go around for those banks that need capital, it remains unclear just which banks and thrifts would be eligible.

Experts have speculated that regulators want to avoid giving funds to simply keep unhealthy institutions alive, such as those banks on the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. so-called "problem bank" list. Letting some of these banks fail could be a way of clearing the dead wood from the system.

It is believed that the government would rather deliver funds to companies that probably would be able to muddle through the credit crisis on their own but would be more willing to start lending again if they had a little assistance.

Regulators have declined to offer specifics about how they will make that determination but have indicated they would consider a number of factors, including the health of an institution, its access to other sources of capital and its ability to lend.

Maybe the most pressing question, however, is whether the capital plan will indeed work.

One fear is that providing capital to U.S. banks would prompt some companies to use the money to plug holes in their balance sheet instead of what the government intended: lending it back out to consumers, businesses and one another.

"To some extent they will have to lend, but at the same time I think banks will want to conservatively build their capital position," said Jennifer Thompson, regional banking analyst at the New York-based financial services research firm Portales Partners.

But banks have effectively raised the barrier to lending in recent months, turning away more potential borrowers than they would have in the pre-credit crunch days. As a result, a capital injection may not necessarily result in more lending as banks continue to steer clear of risky borrowers.

"I don't know if lending will pick up that much," said Cummings, about the impact of capital on lending by regional banks.

And there has also been speculation that some banks may simply take the capital to fuel growth, particularly via acquisitions.

Regulators have said they will be considering this when a bank applies for funds. But even before the program was rolled out, analysts have hinted that consolidation in the industry was inevitable.

Along those lines, an injection of government capital won't necessarily ensure a bank's independence. Given how cheaply bank stocks are trading at the moment, some of the stronger banks may increasingly look to scoop up weaker ones.

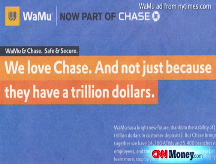

That's already happened with JPMorgan Chase buying failed savings and loan Washington Mutual and Wells Fargo taking over Wachovia.

"There's got to be some consolidation," said Cummings. "There are too many banks chasing too few good customers." ![]()