Health reform FAQ: Cutting through the noise

Confused about what health care reform would look like and how it would change your world? You're not alone.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- Rx: Health reform.

Warning: Headaches may result from trying to figure out what's going to come out of the debate on Capitol Hill.

The proposals under consideration are incomplete. But the rhetoric is rich. So if you're having a hard time making sense of it all, we hope this will help.

Here are 5 common concerns about overhauling the health care system and what we know ... so far.

- Would a public plan hurt private insurers?

- Would a public plan kill employer coverage?

- How much would health reform really cost?

- Can we afford not to do health reform?

- Would reform improve my health care?

President Obama and Democratic leaders have proposed setting up a national insurance exchange. The exchange would serve as a supermarket of plans and let consumers comparison shop for the policy that best suits their needs.

One of the options on offer would be a government-run public plan. Since it's not clear how much public plan premiums would be or what services the plan would cover, it's not clear how many people using the exchange would opt for the public option over a private one.

Insurers and other opponents say a public plan would be the first step to nationalized health care. The public option would have such large economies of scale and such low administrative costs that private insurers couldn't hope to compete, they say. And, they add, the government would set rules for all insurers, and could subsidize the plan with taxpayer dollars if it needed to.

"Regardless of how it is initially structured, a government plan would use its built-in advantages to take over the health insurance market," the insurance lobbying group America's Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) and the BlueCross BlueShield Association said in a joint letter to Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-Mass.

Supporters say a public plan option would compete with private insurers on a level playing field. It would have to abide by the same set of rules as private insurers, it would have to be self-supporting and it would have to negotiate prices with providers, rather than dictating them.

Robert Reich, who served as secretary of labor during the Clinton administration, said if the point of reform is to reduce the growth in health care costs, having a new competitor that can negotiate lower prices will force private insurers to reduce their costs as well.

"It gives private plans a new set of benchmarks and provides them with incentives to get new deals," Reich said in a conference call with reporters.

That insurers don't like the idea isn't surprising, he said. "It would squeeze their profits and force them to make several reforms."

Those that don't might go out of business. But without knowing specifics about the public plan, it's impossible to place odds on how many insurers would be priced out.

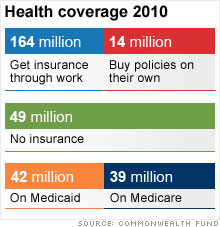

The majority of Americans are insured through their employers' plans. Several reform proposals under consideration would impose a "pay or play" requirement on many businesses.

Translation: A company that didn't provide insurance for its employees would have to pay money to subsidize its workers' purchase of health insurance on the national insurance exchange.

Opponents of a public plan say it would sound the death knell for the employer-sponsored system.

"A government-run plan would dismantle employer-based coverage, significantly increase costs for those who remain in private coverage, and add additional liabilities to the federal budget," AHIP and BlueCross wrote to Kennedy.

Obama says repeatedly that if you like the plan you have, you would be able to keep it. "What I'm saying is the government is not going to make you change plans under health reform," he said on Tuesday.

That doesn't mean, however, that some employers might not opt to drop the coverage they offer and instead opt to pay money to subsidize their workers' purchase of insurance on that exchange.

How many? "I don't think anyone has an answer to that. The details really do matter," said Roberton Williams, a senior fellow of the Tax Policy Center.

Much will depend on how a "pay or play" mandate is set up.

"If the cost of paying [into the exchange] is high enough, employers are more likely to play," Williams said. Conversely, if it's low enough, it may make more financial sense to drop coverage and send employees to the exchange to pick their own plan.

Preliminary estimates have placed the cost in the $1 trillion range. But that's based on estimates of discrete portions of proposals. The real estimated cost of reform will depend on how all portions of the final plan are expected to interact with each other.

But it's a cost that Obama has insisted lawmakers pay for so that health reform will be deficit neutral. So if a bill is estimated to cost $1 trillion, lawmakers will have to come up with $1 trillion to pay for it through spending cuts and tax increases. No borrowing allowed.

But making a bill deficit neutral on paper is different from making it deficit neutral in practice.

A number of health reform measures have never been tried before. So whether they work and how quickly they work will affect the ultimate price tag.

So, too, will lawmakers over the next several years if they opt to tweak the health reform policies they put in place today.

There's a lot of disagreement over how to reform health care. But there is agreement that something must be done to curb the growth rate in health care costs.

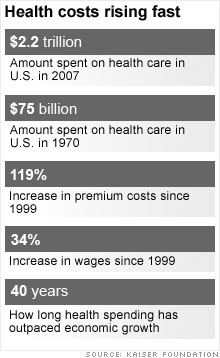

That growth rate has outpaced inflation and wage growth by wide margins for 40 years.

Barring any changes, the United States is on track to spend 20% of its gross domestic product on health care in the next 10 years. The numbers just grow worse from there.

The country's already record high debt is set to swell to unsustainable heights due largely to rising health care costs, which expand federal spending on Medicare and Medicaid.

That can slow economic growth and jeopardize the United States' creditworthiness in the eyes of foreign investors. Those investors may start demanding higher interest rates when they buy U.S. Treasurys. That, in turn, would make the country's debt picture even grimmer.

So health reform is critical. But it will only help if it succeeds.

To the extent that reform succeeds in providing access to more affordable health care, those who can't afford health insurance now might be better off physically and financially.

And a lot of the proposals to curb costs could, in theory, ultimately improve care.

For instance, reformers want to start reimbursing health care providers for better health outcomes rather than paying them a la carte for the number of visits, hospital stays and tests conducted. In other words, they want to pay for quality of care rather than quantity.

The chances of achieving those better outcomes could be fostered by other reform measures: making health records electronic so your bevy of doctors will all know your medical history and prior care. And there are proposals to compare different treatment regimens being employed across the country for similar conditions and then come up with a best-practices recommendation that doctors can use as a reference.

But there is no way to predict whether their promise will become reality.

"Unfortunately little reliable evidence exists about exactly how to implement those types of changes," Congressional Budget Office Director Douglas Elmendorf said in a letter to the Senate Budget Committee.

That doesn't mean they can't be implemented well. But it may take time and experimentation, to say nothing of attention.

So far much of the public debate has been focused on financing reform and covering the uninsured.

"It's not been too much on how we pay for hospitals and doctors," said Paul Fronstin, director of the health research program at the Employee Benefit Research Institute.

But that will be the trick to improving care, he said. "It's not going to be insurance reform. It's going to be delivery reform." ![]()