Search News

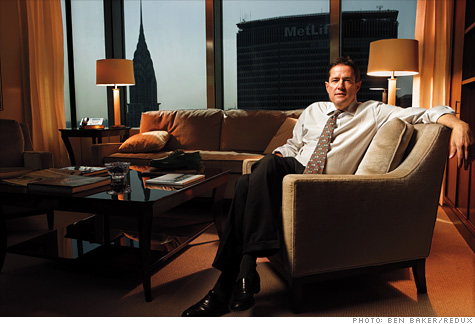

Jes Staley, photographed at his office in J.P. Morgan Chase's Manhattan headquarters, took on his new responsibilities in September as head of the firm's investment bank.

Jes Staley, photographed at his office in J.P. Morgan Chase's Manhattan headquarters, took on his new responsibilities in September as head of the firm's investment bank.(Fortune) -- Jes Staley is a throwback to an old idea of what a banker ought to be. Soft-spoken and client-focused, he has spent his entire career at one company. He's so far below the radar that most people outside finance have never heard of him.

That may be about to change. Last September, after 30 years of toiling in relative obscurity at J.P. Morgan Chase (JPM, Fortune 500) and its predecessors, Staley was chosen to head its $28-billion-a-year (in revenue) investment bank -- one of the most visible and influential posts on Wall Street.

He got the job by earning the confidence of a hard-to-impress guy, J.P. Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon. "Jes has impeccable character and integrity," Dimon tells me. "You wouldn't find many people inside J.P. Morgan Chase who wouldn't say that he was the obvious candidate for the job." And perhaps even another one: Staley is widely considered the executive who would run the bank in the unlikely event Dimon stepped down today.

Staley, 53, didn't exactly come out of nowhere; he's a remarkably successful executive who's been hiding in plain sight. For the past decade he ran the bank's asset management business, expanding it from $605 billion in client assets in 2001 to nearly $1.3 trillion today -- making it the largest shop on Wall Street. (During the meltdown, investors fled shaky funds and flocked to J.P. Morgan Chase, which emerged early on as one of the healthiest U.S. banks.) Before turning around asset management he ran the company's private bank, and before that he helped build its equity capital markets capability.

Through it all, the Bowdoin economics graduate (class of 1979) burnished his reputation as a smart, strategic executive, and a refreshingly straightforward one. "With Jes there is no innuendo. There is no gray area. His yes means yes. His no means no," says Britt Harris, chief investment officer of the Teacher Retirement System of Texas. "He has a well-developed sense of right and wrong, and with that sense, he is able to make decisions a lot more easily than most people."

James E. "Jes" Staley was born Dec. 27, 1956, in Boston. The family moved around the country as Staley's father, a corporate executive, changed jobs, eventually settling just outside Philadelphia, where the elder Staley served as president of PQ Corp., a small chemical company. After Bowdoin, Jes Staley took a job with Morgan Guaranty Trust Co. of New York, a corporate descendant of the storied House of Morgan.

As trainees, Staley and his peers studied the case of real-life banking client W.T. Grant stores, the Wal-Mart of its day, which filed for the second-largest bankruptcy in American history in 1976. At the time it was the largest-ever loan loss for Morgan. Grant's top executive: one Edward Staley. "It was about what the bank did wrong in terms of its loan, but the real bad guy, the one who ran the firm into the ground? That would be my grandfather," says Staley. His younger brother Peter says that if Jes ever does take over from Jamie Dimon, it would constitute the revenge of Edward Staley.

When Staley joined Morgan, much of the action for the bank was in Latin America. Staley joined the Brazil desk and, in March 1982, moved to Brazil itself. The Latin American debt crisis hit in September, ultimately taking down a Brazilian investment bank that Morgan owned half of called Banco Interatlântico. "We brought some of the best and brightest we had from London and New York in to run it," says Staley. "It took us four years to run it into the ground."

Staley met his future wife, Debbie, shortly after arriving in South America. "I was Unitarian Boston American and she was Jewish Brazilian São Paulo," he recalls. "I was her parents' worst nightmare." The couple honeymooned in Bequia, a small island in the Caribbean. More than 25 years later, Staley named his custom-built, 90-foot sailboat after the island.

While still in Brazil, in the fall of 1985, Jes got the news that his brother Peter had been diagnosed with HIV. Peter says he was afraid to disclose his illness to his older brother, convinced that Jes was a homophobe. "He hadn't even realized that right there under his nose, somebody he loved was gay," says Peter, who later founded an AIDS research group. (He has been taking successful antiretroviral therapy since 1987.)

Peter's challenge brought the brothers closer together, and Jes has become an advocate for diversity within J.P. Morgan. In 2002, when the Human Rights Campaign introduced its ranking of Fortune 500 businesses on measures of importance to the gay community, J.P. Morgan Chase scored 100%.

Jes Staley's Brazilian adventure came to a close at the end of the 1980s. By then he was head of corporate finance for Brazil and general manager of the brokerage operation there. But, he says, "New York is the big leagues. So we moved."

Once in New York, Staley was tapped to run the company's fledgling convertible-securities trading desk. He was promoted to head of the equities division, which he took from the back of the pack to sixth place among Wall Street underwriters as measured by capital raised. In 1999, Douglas "Sandy" Warner, then CEO, asked Staley to take over the company's struggling private bank. Soon, however, Staley and his J.P. Morgan colleagues would have new bosses.

In September 2000, the financial world was shocked at the announcement that Chase Manhattan bank was buying J.P. Morgan for $36 billion. Staley continued to lead private banking at the combined company, adding the asset management division to his portfolio in 2001.

He decided to sit down with his company's largest corporate client at the time and get a read on how J.P. Morgan was doing. He asked Allen Reed, then chairman of General Motors Asset Management, to give it to him straight. "You're mediocre at best," Reed told him. "You're just not very good at it."

As Staley was trying to jump-start morale and performance in his group, he attended a 2003 conference at which he heard money managers describing the hedge fund industry as a bubble. But Staley, who thought the rise of alternative investments signaled a change in investors' appetites, had his eureka moment.

Instead of continuing to battle it out in the world of long-only relative performance investing, J.P. Morgan would wade into the absolute-return waters by buying a hedge fund. He knew which fund he wanted: Highbridge Capital Management. Highbridge founders Glenn Dubin and Henry Swieca were already managing some client assets for him. It was the kind of move that can make or break a career.

The company's board was lukewarm to the idea. Former AlliedSignal CEO Larry Bossidy made a telling remark. "The moment a big bank like J.P. Morgan buys a place like Highbridge, all the best people will leave," Bossidy said. That was Staley's opening. "I told them that was exactly why we had to do it," he recalls. "If I couldn't convince our board -- let alone our clients and our people -- that we could hire and retain the best talent in the industry, then I wanted to go back to investment banking. I didn't want to run a business where everyone believed that mediocre was the best I could do."

Jamie Dimon, who had arrived on the scene as a result of the merger of J.P. Morgan Chase and Bank One, concurred with the board. His first response to Staley was concise: "No." Too many hedge funds, he argued, relied on the talent of their founders. Lose the founder and you've got nothing. Staley countered that Highbridge wasn't a personality-driven place. He won over his boss when he pointed out a wrinkle in the deal. In exchange for ongoing performance incentives, the Highbridge team had agreed to an upfront sale price of $700 million. That would make the return on equity of the transaction one of the highest the bank had ever achieved. "Jamie got it immediately," recalls Staley. "Very few people saw it, but he said, 'Well, that's it, you've got to do it.' "

When J.P. Morgan announced in September 2004 that it was acquiring a majority interest in Highbridge, the hedge fund had $7 billion under management. By the end of 2009, when J.P. Morgan bought the rest of Highbridge, it had $21 billion. Dubin, who has stuck around despite being made a billionaire in the process, just signed on for a second five-year term as CEO of Highbridge. He says it's all because of Staley, who increased revenue at the asset management division to $7.97 billion, more than double 2001 levels.

There's no question that J.P. Morgan Chase's investment-banking business is the riskiest that the bank is engaged in. For that reason Dimon has made it clear that candidates to succeed him must have experience running the unit. By 2009, co-CEOs Steve Black and Bill Winters had turned around the business and steered it deftly through the credit crisis, putting it on track for a record year in both revenue and earnings -- $28.6 billion and $6.9 billion, respectively. But Dimon had decided by the end of the year that neither man was going to replace him. So he made changes. Black was kicked upstairs, Winters left the firm, and Staley was put in charge of the investment bank.

It's a new kind of challenge for Staley: Unlike his previous assignments, this isn't a business that needs a turnaround. That's not to say he won't be aggressive in running it. At the company's February investor day, he laid out ambitious market-share targets. He also announced a 17% return-on-equity target for 2010, a decrease from 2009's outsize return of 21%, but well above the investment bank's average of 12% over the past economic cycle.

On the technology front, the bank plans to roll out new trading "platforms" for both equities and commodities over the next three years. "J.P. Morgan was late to electronic trading and is not going to make that mistake again," says Morgan Stanley analyst Betsy Graseck. And whereas the bank garnered 9.2% of all investment banking fees in 2009 -- the No. 1 position -- it is seeking to capture a square 10% in 2010. It hopes to do that, in part, with an aggressive push in Asia, where the objective is to see investment-banking fees nearly double.

In 2010, Staley is gradually emerging from the discreet persona he has cultivated for his entire career. In February he and his wife held a fundraiser for New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand at their apartment. A Democrat like his boss, Staley has shown his support for the party, but like Dimon as well, he has found himself getting frustrated with some of the Washington rhetoric aimed Wall Street's way. "I was a major supporter of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee," he says. "But I wouldn't give money to that group now."

His recent election to the board of Robin Hood, the poverty-fighting organization, was approved unanimously by a board that's a who's who of New York power players, including hedge fund luminaries Steve Cohen, Highbridge's Dubin, and Paul Tudor Jones, as well as GE chairman Jeff Immelt and Tom Brokaw. Outside Bowdoin, it's his only major time commitment.

That's understandable. After all, he's got one of the most pressure-packed jobs on Wall Street. And while Staley has done turnarounds, one thing he hasn't done is hold onto first place as formerly wounded competitors come roaring back. "J.P. Morgan was a market-share consolidator last year, when they were capital-strong and open for business," says Jeff Harte, an analyst at Sandler O'Neill & Partners. "But the one thing you can count on in investment banking is that when times are good, the competition will come."

Does Staley think about the fact that he could very well be the next CEO of J.P. Morgan Chase? Of course he does. But he also knows that Dimon hasn't said he's going anywhere, and it's unlikely that his boss is going to wake up next week with a change of heart. With shares of J.P. Morgan Chase trading at just about where they were when Dimon arrived six years ago -- in the mid-40s -- it's hard to see him wanting to leave just yet. Pride alone demands he get the stock to $60 or higher before moving on. That could take a while.

Staley also knows that he's the same age as Dimon and that his boss is looking at younger succession candidates too. That includes chief financial officer Mike Cavanagh, 43; retail head Charlie Scharf, 44; and asset management CEO Mary Erdoes, 42. There's also Matt Zames, 39, a rising star in the investment bank.

"If Jamie doesn't leave, then I probably need to leave myself in a few years," says Staley. "If it's not me, it's still been a blast working for Jamie. He is one of the greatest people in finance in my generation. At that point, I am going take an office at Highbridge and sail."

It's not too difficult to believe him, given that his office is practically a shrine to the art and craft of sailing. Staley downplays the size of the Bequia, a pilothouse yawl, even though it is quite clearly a thing of beauty. "It's not a big yacht," he says, "but it is a big boat." He's right. Don't be surprised if his boss, Jamie Dimon, taps him to become captain of a bigger vessel yet.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified Highbridge Capital Management as Highbridge Asset Management. It also stated that Stan Druckenmiller was a board member of the Robin Hood Foundation. Druckenmiller is no longer on the board. ![]()

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |